Jun 22, 2015

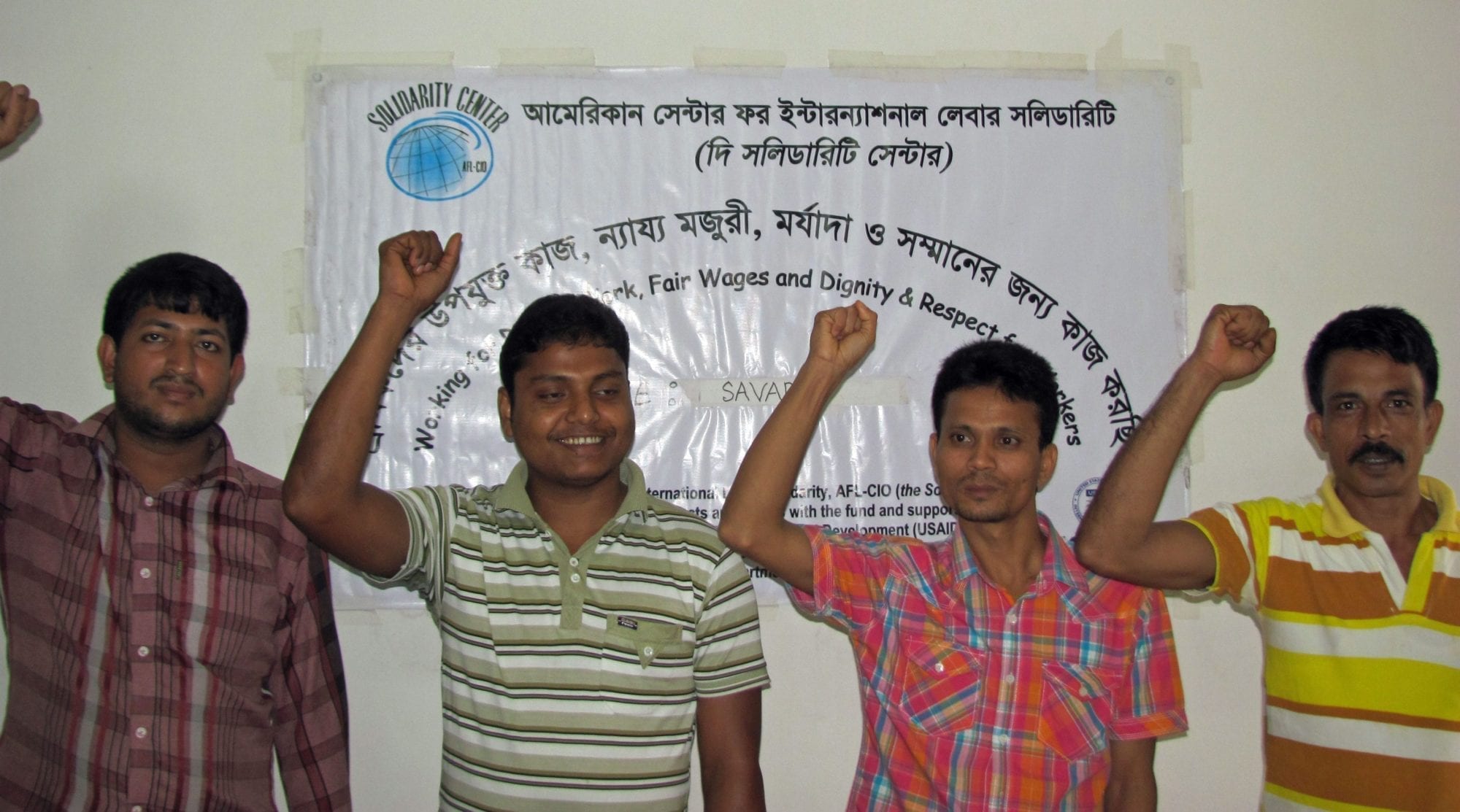

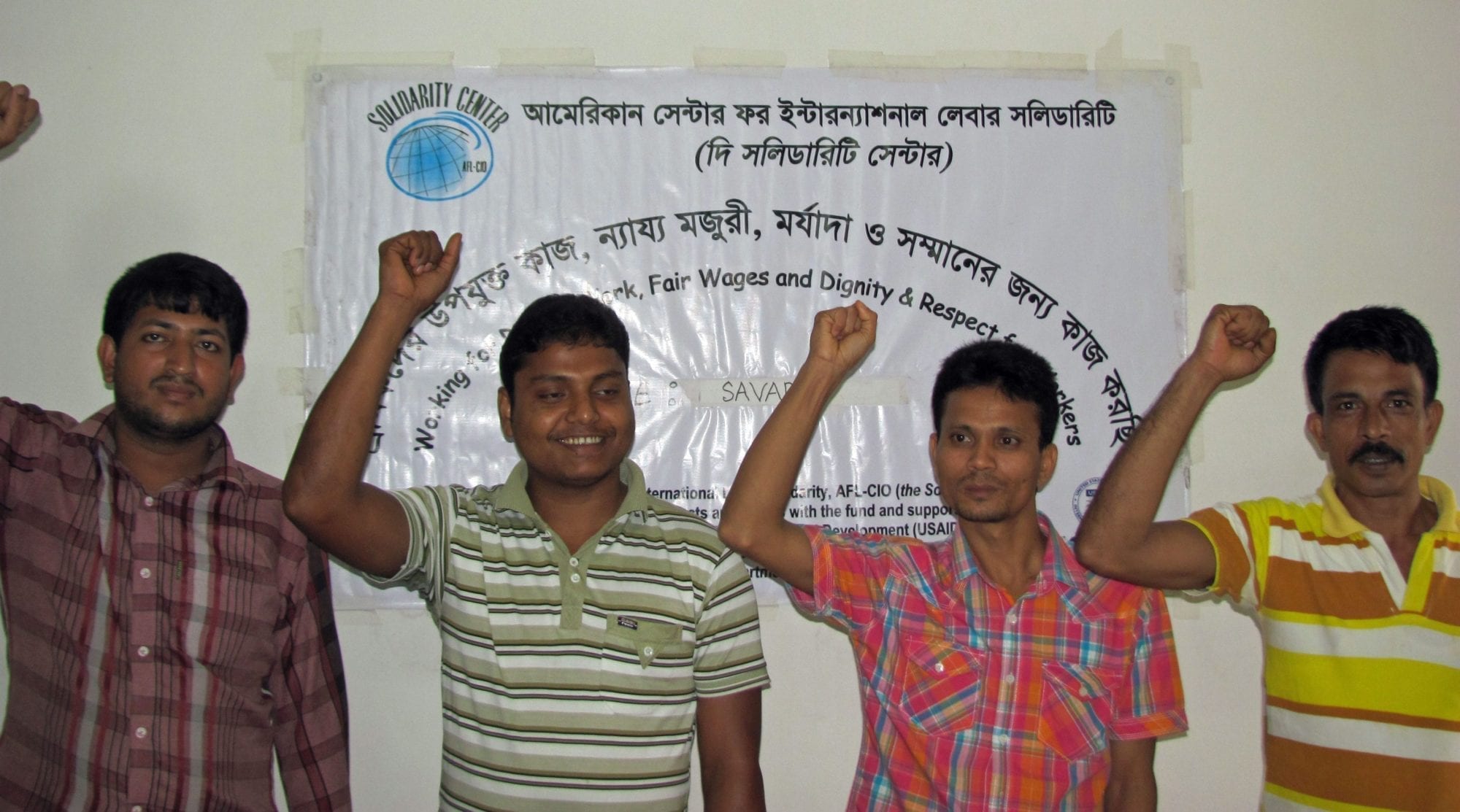

When Rafikul Islam, 25, president of a workers’ welfare association at a factory in the Dhaka export processing zone (EPZ) heard that one of the top factory officials harassed the female staff member responsible for the factory’s day care center, he took action.

“We called a meeting of our association and decided that we would protest this incident and write to the authorities to take action against the official,” Rafikul says. After they lodged a complaint, the official was terminated.

“This was possible because we were united. We never imagined such immediate action when there was no union in the EPZ.” Rafikul said there were similar incidents in other factories in the past but the victims did not get justice.

Despite obstacles, workers’ welfare associations are gaining ground in factories throughout Bangladesh’s export processing zones. Bangladesh derives 20 percent of its income from exports created in the EPZs, which are industrial areas that offer special incentives to foreign investors like low taxes, lax environmental regulations and low labor costs. Some 377,600 workers, the vast majority women, work in 497 factories in Bangladesh’s eight EPZs.

EPZ workers had long been denied the freedom to form unions, but in 2010, a law passed enabling workers to form unions under a different name—workers’ welfare associations. Associations are permitted to represent workers on disputes and grievances, negotiate collective bargaining contracts and collect membership dues. Now in the Dhaka EPZ alone, 40 of the 103 factories include workers welfare associations.

But unlike traditional unions, the associations cannot interact nor affiliate with any labor union, nongovernmental organization or political organization outside the EPZ. Associations can only form a federation within one zone.

Kholilur Rahman, 20, general secretary of an association of another factory in the Dhaka EPZ says that after forming an association, workers became aware of their legal rights.

“Most of the workers in our factories were contractual workers,” he says. “Authorities did that purposefully to deprive us from receiving benefits. But after forming the association, the factory management made us permanent,” Kholilur said.

Oliur Rahman, a member of an association in the Dhaka EPZ, says that in the past, managers terminated them for trivial reasons.

“But this is not the case after we formed an association and voted for our association and elected the officers for our workers’ welfare association,” he said.

Jun 19, 2015

Héctor Martínez Motiño, president of a local sectional union of Workers of the National Autonomous University of Honduras (SITRAUNAH), was murdered Tuesday, shot by gunmen as he drove home from work.

Martínez Motiño, a lecturer at the Choluteca campus of the National Autonomous University of Honduras, in the south of the country, had faced three other attempts on his life and numerous anonymous threats, the result of his reporting of violations of human and worker rights within the university.

He took his complaints of harassment to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, which issued a “precautionary measure” demanding that the Honduran government provide protection for him and his family as his union work put him in danger. The Commission “may request that a State adopt precautionary measures to prevent irreparable harm to persons or to the subject matter of the proceedings in connection with a pending petition or case, as well as to persons under the jurisdiction of the State concerned, independently of any pending petition or case.”

Despite these measures, Martínez Motiño reported feeling unsafe. On Facebook, he posted: “Despite these measures, I continue to be harassed, followed, threatened and the target of attempts against my life. I ask God and all of you to keep us in permanent prayer.”

According to news reports, he had no police protection at the time of the attack. With this murder, 14 people with protective measures have been assassinated, according to the website Defensores en Línea. On April 8, Donatilo Jiménez, president of another local sectional union of university workers SITRAUNAH from the Atlantic Coast, was kidnapped and disappeared; to date, only his vehicle has been found. An MS-13 gang leader has been arrested in connection with this crime.

Martínez Motiño was a member of the Honduran Network Against Anti-Union Violence, an effort of labor union activists and the human rights non-governmental organization ACI-Participa, supported by the Solidarity Center. The network, Honduran labor movement and ACI-Participa condemn the “vile murder” and are demanding a full investigation.

Jun 19, 2015

Solange Ambroise sells vegetables in the San Cristobal Municipal Market. Credit: Solidarity Center/Ricardo Rojas

Rarely do governments admit failing their citizens. However, on Friday the 193-member states of the United Nations did just that when they voted to rectify their failure to uphold the rights of workers and to ensure decent working conditions for more than half of the world’s working women and men.

By voting for an International Labor Organization (ILO) recommendation, The Transition from the Informal to the Formal Economy, the large majority of the world’s governments has done more than just pledge to provide the basics for the world most vulnerable workers—those struggling to make ends meet in the informal economy—they have begun the essential process of strengthening society by promoting worker rights.

Street vendors, home-based workers, domestic workers and day-laborers usually work “off the grid” and outside a country’s regulations and labor laws. They join subcontracted, temporary and part-time workers who subsist on the fringes of the formal economy. These jobs typically pay low wages, perpetuate worker and human rights violations, provide limited or no social benefits, and offer little access to union representation. For most of these workers, survival trumps active engagement in society’s daily undertakings.

An estimated 1.5 billion, or approximately 60 percent of the world’s workers, toil in the informal economy, according to the ILO. In some developing countries, informal jobs comprise up to 90 percent of available work, and most workers take these unstable jobs out of necessity, not by choice.

Women, migrant workers and the young are disproportionately represented in the informal economy, and often the most exploited. Their situation is exacerbated because they may be barred from joining unions, which could offer support through collective bargaining on wages and working conditions, or because unions have not been able to reach them due to the isolated and changeable nature of their job.

Informalization of work fuels global income inequality, poverty and abuse. For example, at age 22, N. Naga Durga Bhavani left her small village in India for Bahrain, where she hoped a job as a domestic worker would help pay for her young daughter’s heart surgery. But when she arrived, after paying labor recruiters the equivalent of nearly two months’ wages, she says her passport and papers were confiscated, and she was forced to work long hours, trapped in an abusive environment where she was beaten, her fingers broken. After she escaped, the Indian Embassy could not help her leave the country because she had no identification.

And the drag on society does not end with the desperate plight of workers like Bhavani. Businesses employing workers in standard employer-employee relationships find themselves at a distinct disadvantage when they compete against those chasing short-term profits by not hiring full-time workers, paying taxes and benefits, or complying with regulations and labor law. Companies that provide financial and business services miss huge swaths of potential clients whose income leaves them too poor to enter the shop door and unable to access credit.

The effects on government are even more profound. The loss of tax revenue on huge percentages of GDP in many countries is only one edge of the sword. Because workers in the informal economy usually hang from the bottom rung of the economic ladder, they are more likely to need social safety nets—the very nets their jobs do not support through tax revenue.

Friday’s vote is significant because governments, worker representatives and employer representatives, who usually operate with very different agendas, publicly acknowledged the imperative of providing all workers with rights at work, social benefits and the ability to join a union. Their acknowledgement that the current system does not work—not for working people, not for governments and not for the businesses that serve them—is an important step toward bringing millions of workers into decent jobs that comply with labor codes and allow workers to be stronger members of their society. All of us should applaud the 193 nations for not choosing failure.

Jun 19, 2015

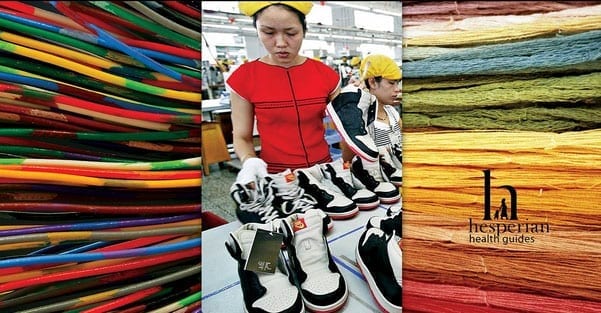

The new Workers’ Guide to Health and Safety, published last month by Hesperian, is not only geared for working people, but was created with the input of workers around the world who ensured the guide includes helpful information in an easily-accessible format, says Miriam Lara-Meloy, a project coordinator at Hesperian Health.

The new Workers’ Guide to Health and Safety, published last month by Hesperian, is not only geared for working people, but was created with the input of workers around the world who ensured the guide includes helpful information in an easily-accessible format, says Miriam Lara-Meloy, a project coordinator at Hesperian Health.

Workers from 25 countries “gave us feedback on the book” in addition to technical review by experts, educators and worker advocates, says Lara-Meloy, speaking recently at the Solidarity Center’s Washington, D.C., office. Solidarity Center staff contributed to the review process.

The guide’s content covers issues such as chemical exposure, fire safety and ergonomics, with step-by-step procedures to follow in case of accident or injury. But the book also addresses issues like workplace sexual harassment and pollution outside the plant, recognizing that workers’ well-being also depends upon broader societal issues.

Further, says Lara-Meloy, the book is written to address the workplace “power dynamic”—one in which workers, especially young workers, find it difficult to approach their employer about making health and safety improvements.

The guide covers all issues from a social justice perspective, says Lara-Meloy, and ultimately, “the goal is to take action, join with others, create solid campaigns.”

Hesperian Health Guides, a nonprofit organization based in Northern California, produces easy-to-understand health information and educational tools, which have been translated into more than 80 languages. All materials, except for recent publications, are free and downloadable.

Jun 17, 2015

Hundreds of thousands of workers in the Dominican Republic without official identification papers have until today to register with the government or face deportation. The move—condemned widely as a violation of human rights—could leave as many as 120,000 Dominican-born and -raised women and men stateless, their future and their ability to earn a living jeopardized. If they cannot regularize their status, their next stop, as soon as tomorrow, may be the Haitian border.

Dominicans of Haitian descent have long faced exploitation and discrimination and experienced trouble obtaining official documentation, despite spending their entire lives in the country. Many speak only Spanish and have few, if any, ties to neighboring Haiti. However, a controversial 2013 Constitutional Court decision ruled that that individuals who were unable to prove their parents’ regular migration status could be retroactively stripped of their Dominican citizenship. While a later presidential decree recognized the citizenship of roughly 68,000 people, an additional 130,000 Dominican natives who never had documents were forced to prove birth in the Dominican Republic country to apply for Haitian citizenship and, with Haitian documents, apply for regularization in the country of their birth. Only about 10,000 of these people applied under the plan.

A 2014 report by the Solidarity Center and AFL-CIO, “Discrimination and Denationalization in the Dominican Republic,” called the ruling an “egregious abuse of fundamental human rights and a clear violation of international law.” Indeed, said the report, the actions by Dominican officials leading up to and following the ruling “demonstrate the depths of entrenched discrimination.”

In September 2014, Dominican unions and human rights groups raised concerns that the registration process was fraught with irregularities, unnecessary hurdles and bureaucracy. They said some local agencies were charging exorbitant fees for documents that were supposed to be provided for free and which applicants needed to demonstrate long-term residence. They said some workers had waited months for notification of the results of their applications, even though the law stipulates a response within 45 days.

Said Alexis Rosalie, spokeswoman for the National Coordinator for Immigration Justice and Human Rights and an organizer for the National Federation of Workers in Construction and Building Materials (FENTICOMMC), at the time: “We have proof there are people who meet all the basic requirements of the National Plan for Regularization of Foreigners (PNRE), and each time they go back to the offices, they are always told they are lacking one document or another.”

According to a report today by The Guardian newspaper, only 300 people applying for official identification received it.

Shawna Bader-Blau, executive director of the Solidarity Center, said: “We are astounded by this deliberate creation of a stateless underclass. Tens of thousands of people who live on the margins today and could be separated from their loved ones, their social networks, their jobs—all that is keeping them barely afloat—tomorrow.”

In past weeks, representatives of the Network of Support to Migrant Workers of the National Confederation of United Trade Unions (CNUS) and the Migrant Justice Movement, a grouping of unions and migrant organizations formed at a 2014 advocacy training organized by the Solidarity Center, held a series of press interviews calling for an extension to the regularization plan. Other groups, including Amnesty International, are calling on the government to respect international law and standards, and to “establish adequate mechanisms to avoid the expulsion of Dominican-born people who were deprived of their Dominican nationality in September 2013, including a specific screening process targeting Dominicans of Haitian descent.”

The new

The new