Apr 28, 2015

Garment workers practice emergency techniques during a Solidarity Center fire safety training. Credit: Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

Safe and healthy jobs are among workers’ most fundamental rights, and each year on April 28, World Day for Safety and Health at Work, the global labor community shines a spotlight on these rights. Workers and their unions commemorate those who lost their lives on the job and hold events and informational activities to raise awareness of the need for workers, employers and governments to actively participate in securing a safe and healthy working environment.

Through unions, workers achieve the strong, collective voice needed to improve safety and health at the workplace. In Bangladesh, where the deadly Tazreen Fashions Ltd. factory fire killed 112 garment workers in 2012, and where at least 41 garment workers have perished in fire incidents since then, more and more workers are seeking unions to ensure their factories are safe.

In recent months, dozens of garment workers have taken part in the Solidarity Center’s fire safety training program, a 10-session course that aims to equip union leaders with essential knowledge and skills on workplace safety. The workers then educate their co-workers and strengthen their unions’ ability to raise and rectify unsafe factory working conditions.

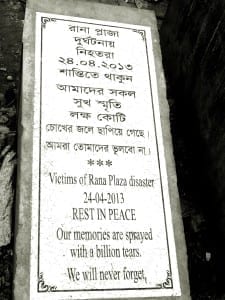

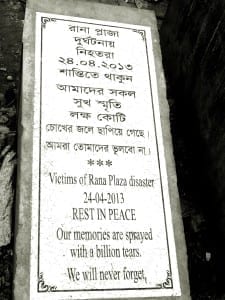

“People who worked at Tazreen and Rana Plaza had no training and had no union,” says Saiful, referring to the Rana Plaza building collapse that killed more than 1,130 garment workers in 2013. “This training is about making sure those things never happen again.” Saiful, a union leader from Radisson Apparels, took part in the most recent fire safety training

Participants who successfully completed a fire safety training take part in a closing ceremony. Credit: Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

Urmi, a union organizer, agrees. “Thousands of people died (as a result of Rana Plaza and Tazreen). We need to know what to do and have, and give workers the confidence to be leaders in their factories.”

In the program’s next stage, the Solidarity Center and the union leaders who have participated in the training will begin training workers at their factories.

Morshed Hossain a union leader from Step III Apparels Ltd., says he organized a union at his factory so workers could push for clean toilets, respect from supervisors and their due wages. Morshed said that midway through the fire safety training in March, he went back to “talk to the other workers in my factory about what to do in case there is a fire.”

Abdul Hakim, a union organizer who also took part in a fire safety training, said “before this training, we were not aware about workplace safety. But now we know what to do and how we can talk to workers.”

As Solidarity Center Bangladesh Country Program Director Alonzo Suson said during a ceremony marking the conclusion of the first fire safety training last July:

“Workers around the world have found that, by forming unions and speaking with a collective voice, they are better able to ensure safer working conditions. These new union leaders will be able to take what they’ve learned back to their co-workers to make their factories better, healthier and safer places to work.”

Apr 27, 2015

With thousands of people dead and even more made homeless in Nepal following a devastating magnitude-7.8 earthquake, Solidarity Center union allies in the country are reporting no casualties among their staff and are organizing to support relief efforts in the Nepali capital.

The General Federation of Nepalese Trade Unions (GEFONT), which represents mostly blue-collar workers, the Nepal Trade Union Congress (NTUC), which includes teachers and other white-collar workers and the Joint Trade Union Coordination Center (JTUCC), the umbrella organization of GEFONT and the NTUC, say their employees are safe and now working to provide disaster relief. Both GEFONT and the NTUC represent many workers in the tourist industry.

“Kathmandu valley is unimaginably destroyed,” says Bishnu Rimal, GEFONT president. “It is the most terrible quake we have ever experienced. Chilling cold, plus rain, lack of tents and [continuous] jolts is sufficient to scare people. It has disturbed even rescue work.”

The earthquake hit central Nepal on Saturday, from Mount Everest to Kathmandu and further west, wiping out entire villages. As rescue teams began to arrive from around the world, much of the stricken area remained inaccessible, locked in mountainous terrain with some roads blocked by landslides.

In letters to Rimal and Khila Dahal, NTUC general secretary, AFL-CIO President Richard Trumka expressed heartfelt condolences and solidarity.

“We will … work with the global labor movement to ensure that the working families impacted by this tragedy receive the support needed to rebuild their communities,” Trumka said.

The earthquake and aftershocks were felt as far away as Dhaka, Bangladesh, where one garment worker was killed and more than 200 injured as workers rushed out of factories when the quake hit.

At least one worker reported to Solidarity Center staff there that he took successful safety measures at his factory when the quake hit because of skills he learned at a recent Solidarity Center’s fire and building safety training. In recent months, the Solidarity Center has held a series of safety trainings for garment workers near Dhaka and Chittagong, where most factories are located. The 10-day trainings provide workers with hands-on fire and building safety experience, which includes steps to take during earthquakes.

Apr 27, 2015

Mércia Silva, director of Brazil’s InPacto, an organization focused on eradicating forced labor in businesses and their supply chains, often must meet with owners and managers of companies where forced labor exists. But she doesn’t approach them “with theory,” she says.

“I take a photograph of a worker working under extremely difficult conditions and I ask them, ‘Would you like someone in your family to work like this?’ ‘Of course not,’ they say, and from there we are able to make change.”

Silva shared her strategies for empowering workers last week on the panel, “Raising the Floor—Fresh Thinking to Improve Working Conditions and Workers’ Rights,” a discussion on worker-driven strategies to improve conditions for workers enduring the most abusive conditions. The panel was part of a two-day, two-city International Labor Organization (ILO) conference, Out of the Shadows: Innovative Approaches to Combating Forced Labor and Other Forms of Worker Exploitation.

“The presence of forced labor in society doesn’t happen in a vacuum,” said Solidarity Center Executive Director Shawna Bader-Blau. “Forced labor is created by policy. And change comes from the demands and voices of workers and their unions standing up for their rights, standing up for better treatment.” Bader-Blau facilitated the panel, whose primarily U.S.-based participants discussed a range of strategies—including enlisting consumers and the global labor movement—to assist workers in winning their rights on the job.

“You can’t organize anyone with a vague vision,” said Saket Soni, executive director of the National Guestworker Alliance. “These are people who have been staring into the face of evil (forced labor). The alternative has to be concrete. For us, that alternative is, ‘what if you could sit down and negotiate a contract with your employer?’ The only way you can do that is to collectively organize.”

Silva praised Brazil’s Central Union of Workers (Central Unica dos Trabalhadores, CUT) and other Brazil union federations for seeking to make worker rights a reality for agricultural laborers toiling under what she described as “horrible working conditions.

“It’s important to open the door to unions” for these workers, she said. The Solidarity Center works with CUT and other Brazil union federations to help empower vulnerable workers. The AFL-CIO and the CUT have a several decade-long partnership to promote fundamental labor rights in the United States, Brazil and across the Americas.

Women make up a large percentage of workers in forced labor, and panel participants pointed to their key role in taking the lead to improve their working conditions. Neidi Dominguez, director of the AFL-CIO Worker Centers and Community Engagement, discussed how even though Los Angeles carwash workers are predominantly male, women workers were among those who stood up and demanded to be paid a regular wage. Until they did, carwash workers were paid on through pooled customer tips.

The conference, held in in Washington, D.C., on April 22 and in Los Angeles on April 24, brought together representatives from civil society, government and business to discuss strategies to prevent and mitigate exploitative labor practices, with a focus on the United States and Brazil. These strategies aim to decrease workers’ vulnerability to forced labor and other forms of worker exploitation.

“Raising the Floor” panelists also included Steve Hitov, general counsel for the Coalition of Immokalee Workers; and Haeyoung Yoon, deputy program director at the National Employment Law Project.

Apr 22, 2015

Rabbi, 10, lost his mother in the Rana Plaza collapse. Credit: Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

Rabbi Sheikh, 10, began crying when talking about his mother, Shirina Akhter. “I always think about my mother,” he said. Two years ago, Shirina was among more than 1,130 garment workers killed when the multistory Rana Plaza building pancaked. Her husband, Latif Sheikh, heard the building collapse as he sold fruit by the roadside. It took him 17 days to find Shirina’s body.

“My son always cries, remembering his mother,” Latif says. “He is not able to lead a normal life like the others at his age.”

As the global community commemorates the April 24 Rana Plaza tragedy, thousands of garment workers who survived the disaster, mostly young women, remain too injured or ill to work, and the families of those killed struggle emotionally and financially to piece together the lives shattered that day.

Solidarity Center staff in Dhaka recently spoke with survivors and the families of those who lost loved ones in the collapse, and all say they are struggling to make ends meet, unable to pay rent, send their children to school or provide for other basic needs.

International labor organizations and prominent retailers created a $30 million compensation fund in 2013 to aid families of workers killed and injured at Rana Plaza. According to the International Labor Organization (ILO), 75 percent of those who sought compensation have received something, but to date, 5,000 people have received only 40 percent of the money due them. Further payments have been delayed because clothing brands have failed to pay the $9 million needed to cover claims. (Download a fact sheet here.)

Bangladesh’s $24 billion garment industry is the world’s second largest, after China, and some 80 percent of Bangladesh’s garment exports are destined for the United States and Europe.

Despite constant pain from her injuries at Rana Plaza, Kohinoor, a single mother, is forced to work to support her children. Credit: Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

Kohinoor is among the luckier Rana Plaza survivors. A single mother, she worked as an assistant at Phantom Apparels, one of five factories in the Rana Plaza building. She received some compensation from several sources, including $625 from the ILO and $562 from Primark, which enabled her to pay her medical bills and support her three children for nine months while she was treated for the injuries she sustained.

Despite constant pain, she works as a cleaner in three homes, but her wages are not sufficient to support school fees, and so her children cannot attend school. Her eldest son helps the family by working in a restaurant.

“Nowadays, I have to be absent regularly from my work, as I don’t find the proper strength to work,” she said. Like all those Solidarity Center staff talked with, Kohinoor would like to be fairly compensated so she can support her family.

Standing in the rubble of Rana Plaza, Mosammat Mukti Khatun describes how her injures at Rana Plaza have made it impossible to adequately support her family. Credit: Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

Mosammat Mukti Khatun, 27, was rescued after spending nine hours in the darkness, pinned in the debris of collapsed cement. She also used all of the compensation she received for medical bills and to support her family while she was recovering. Mosammat still suffers from acute pain, and recently suffered additional injuries at a garment factory where she began working in January. Her husband, a day laborer, makes little money, and with five children, the family is in debt.

“I have no money left to secure my days,” Mosammat says. “I do not know how we will get by without additional support.”

On April 24, garment workers and their families plan to form a human chain at the national press club in Dhaka, before placing flowers at the Rana Plaza site.

Apr 21, 2015

In the initial months after the Rana Plaza collapse on April 24, 2013, a preventable catastrophe that killed more than 1,130 Bangladesh garment workers and injured thousands more, global outrage spurred much-needed changes.

The site of the Rana Plaza building two years after it collapsed. Credit: Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

Dozens of garment factories were closed for safety violations through the Bangladesh Fire and Building Safety Accord process, a legally binding agreement in which nearly 200 corporate clothing brands pay for garment factory inspections. Other inspected factories where problems were identified have addressed pressing safety issues. Workers organized and formed unions to address safety problems and low wages—and the government accepted union registrations with increasing frequency—after the United States suspended its Generalized System of Preferences (GSP) agreement with Bangladesh based upon chronic and severe labor rights violations.

But in recent months, those freedoms are increasingly rare, say garment workers and union leaders.

“After the Rana Plaza and Tazreen disasters, it had become easier to form unions,” says Aleya Akter, president of the Bangladesh Garment and Industrial Workers Federation (BGIWF). But since November 2014, the government is more frequently rejecting registrations, she said, speaking through a translator while at the Solidarity Center in Washington, D.C., this week. The Tazreen Fashions factory fire five months before the Rana Plaza collapse killed 112 garment workers. (Download a fact sheet here.)

Credit: Solidarity Center/Balmi Chisim

Overall government rejections of unions that applied for registration increased from 19 percent in 2013 to 56 percent so far in 2015, according to data compiled by Solidarity Center staff in Dhaka, the Bangladesh capital. Despite garment workers’ desire to join a union, they increasingly face barriers to do so, including employer intimidation, threatened or actual physical violence, loss of jobs and government-imposed barriers to registration. Regulators also seem unwilling to penalize employers for unfair labor practices.

“In our view, a severe climate of anti-union violence and impunity prevails in Bangladesh’s garment industry,” according to a March International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC) report. “The violence is frequently directed by factory management. The government of Bangladesh has made no serious effort to bring anyone involved to account for these crimes.”

Meanwhile, thousands of workers still toil in unsafe factories. In the two years since the Tazreen fire, at least 31 workers have died in garment factory fire incidents in Bangladesh, and more than 900 people have been injured (excluding Rana Plaza), according to Solidarity Center data. The Accord and the non-legally binding Alliance for Bangladesh Worker Safety have nearly completed their inspections, which will total fewer than half of the country’s 5,000 garment factories, including 600 factories that have refused entry to inspectors, according to the International Labor Organization.

In recent months, the Solidarity Center has conducted a series of fire safety trainings for garment workers near Dhaka and Chittagong, where most garment factories are located. The 10-day trainings provide workers with hands-on fire and building safety experience.

Following one recent training, Lima, a factory-level union leader, says she “learned a lot.

“We organized our union in mid–2014. The staircase that workers use in my factory used to be blocked and was a fire hazard. But through our union we took the initiative to talk to management about the problem and now the staircase is clear.”

When garment workers like Lima are allowed to form unions, they have the opportunity to create positive changes at their workplaces, making unions fundamental to substantive improvements in Bangladesh garment factories—an opportunity fewer and fewer garment workers can grasp in the current environment.