Jul 12, 2018

Click here to read what civil society has to say about AGOA.

The goal of the Africa Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) and similar U.S. trade preference programs and agreements should be to reduce income inequality and increase good jobs, say worker rights organizations, unions and civil society experts. Those outcomes will not be achieved unless governments consult with their citizens on deals that impact their lives and livelihoods.

Shawna Bader-Blau, Solidarity Center Executive Director, left, moderates a panel discussion including Caroline Khamati Mugalla, Executive Secretary of the East African Trade Union Confederation. Credit: Tula Connell

Representatives of several African and U.S. nongovernmental organizations and trade unions spoke on July 10, 2018, at a panel discussion in Washington, D.C., “Ensuring Inclusive and Equitable Growth in Sub-Saharan Africa through AGOA,” which focused on the path forward for AGOA in the remaining seven years before it expires in 2025. The event was organized by the Solidarity Center.

“Yes, we want trade. And, yes, we want trade to work for people,” said Shawna Bader-Blau, Solidarity Center executive director, who restated the organization’s decades-long commitment to a rights-based approach to economic policy and rules that work for working people, which Bader-Blau described as “economic development for everyone, globally.”

Africa is not a poor continent, said Caroline Khamati Mugalla, executive secretary of the East African Trade Union Confederation (EATUC). The problem is not poverty, she said, but that “wealth is not getting to the people.”

More than 80 percent of workers on the African continent—of whom more than 50 percent are women—are in the informal sector, which often means, said Mugalla, a lifetime of poverty due to low wages, lack of access to social protections like pensions and health care, and any rights ascribed to workers in the formal sector under national and regional labor laws.

“We are told any job is a good job, but this is not true,” said Mugalla, who argued that the growth of decent employment is central to structural economic transformation of Africa.

Kwabena Nyarko Otoo, director of the Policy and Research Institute of the TUC-Ghana shared on a panel discussion on the way ahead for AGOA. Credit: Tula Connell

“We need to recalibrate AGOA so it strengthens the productive capacities of African countries—so there are more good jobs for Africans,” agreed panelist Kwabena Nyarko Otoo, economist and director of the Policy and Research Institute of Ghana’s trade union federation, Trades Union Congress (TUC). Otoo argued against foreign companies exploiting opportunities provided by AGOA to enrich themselves and top management rather than providing skilled, formal-sector, well-paid jobs to local populations.

“I do think trade tools are incredibly powerful because governments do care. They are somewhat underutilized by civil society groups and labor, especially in the AGOA context,” said Scott Busby, Deputy Assistant Secretary in the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor (DRL) at the U.S. Department of State. “I do think trade tools can and should be part of how we support democracy and human rights.”

“The AGOA labor provision requires countries to make continual progress toward establishing worker rights, including acceptable conditions of work,“ said Matthew Levin, director of Trade and Labor Affairs at the Bureau of International Labor Affairs (ILAB), U.S. Department of Labor. “AGOA hasn’t done everything we wanted, but we’ve had some successes.”

Marie Clarke, Executive Director, Action Aid USA. Credit: Tula Connell

Marie Clarke, executive director of ActionAid USA, said about AGOA that, if we are going to use it as “a tent to address and protect the rights of people,” civil society must insist that the people most affected by policies like trade agreements be at the table—especially when the goal is women’s empowerment and more equitable and just development. To combat exploitation and gender-based violence at work, she added, “women must get to share their experience as a worker, as a woman [at the negotiating table].”

This call for a human rights approach to development was mirrored by Sam Worthington, InterAction chief executive officer. “There is a myth that economic growth leads to development. It does not,” he said.

Inclusive economic growth occurs when the demand for it comes from within, said Worthington, when civil society groups and labor “make it happen.” Support for the trade agreement in Africa will diminish, he warned, unless AGOA is used as a tool for development instead of exclusively for economic growth.

The Solidarity Center’s Molly McCoy, Policy Director, left, with Cassandra Waters, AFL-CIO Global Worker Rights Specialist. Credit: Tula Connell

Workers are always in the best position to monitor and enforce working conditions, said AFL-CIO Global Worker Rights Specialist Cassandra Waters. “The real test is in implementation,” she said.

“You cannot help people if you don’t listen to them,” said Otoo, who advocated for workers to be included in all aspects of trade agreements, including negotiations and implementation.

In a statement distributed at the 17th Africa Growth and Opportunity Act Forum in Washington, D.C. on July 11, 16 civil society organizations called on African and U.S. governments to work more closely with civil society to ensure AGOA trade preferences benefit more than the elite. The forum is attended by trade ministers from sub-Saharan African countries benefiting from AGOA and U.S. government representatives.

AGOA provides preferential access to U.S. markets for qualifying sub-Saharan countries. To qualify and remain eligible for AGOA, each country must be working to improve its human and worker rights record and respect the rule of law. In 2014, the United States suspended Swaziland from AGOA for failing to allow worker and civil society groups to freely associate and assemble. In December last year, after the government had met a series of benchmarks on political freedom, Swaziland’s trade benefits under AGOA were restored.

Jul 11, 2018

The Africa Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) has done little to build economies that work for all Africans but, if better utilized and combined with meaningful commitments to human rights and development, AGOA could undergird the establishment of strong, sustainable and diversified economies in sub-Saharan Africa, say 16 civil society organizations.

In a statement distributed today at the 17th Africa Growth and Opportunity Act Forum in Washington, D.C., the organizations—among them trade unions and anti-poverty, religious, social justice and worker rights groups from Africa, Europe and the United States—called on African and U.S. governments to work more closely with civil society to ensure AGOA trade preferences benefit more than the elite. The forum is attended by trade ministers from sub-Saharan African countries benefiting from AGOA and U.S. government representatives.

The Solidarity Center is among the signatories to the statement, which offers recommendations on economic diversification, worker rights, human rights and closing civil society space, gender equality and corruption.

AGOA, enacted in 2000, has been renewed through 2025. The legislation provides U.S. market access to sub-Saharan African countries that demonstrate efforts to protect worker and human rights, reduce poverty, combat corruption and respect the rule of law.

Jul 3, 2018

A global regulation addressing gender-based violence at work is one step closer to reality following a 10-day meeting of workers, their unions and representatives from business and government—but much work must yet be done to ensure its passage.

Participants at the recent International Labor Organization (ILO) conference in Geneva, Switzerland, reached consensus on the need for a convention and recommendation to provide guidance to member states, employers and unions in implementing a global standard to end violence and harassment at work. ILO conventions are legally binding international treaties that may be ratified by member states, and recommendations serve as non-binding guidelines.

Momentum for an ILO convention covering gender-based violence at work follows years of advocacy by the global union movement, an effort led by the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC).

Leading up to the most recent negotiations, Solidarity Center partners urged their unions, governments and employers to publicly support a binding ILO convention on violence and harassment at work that includes gender-based violence. Their efforts clearly moved countries such as the governments of Tunisia and Cambodia, which both indicated strong support.

With Solidarity Center support, more than a dozen workers—from Brazil, Cambodia, The Gambia, Guatemala, Honduras, Indonesia, Kenya, Mexico, Morocco, Nigeria, Palestine, South Africa, Swaziland, Tunisia and Zimbabwe—participated in the conference. Several took lead roles in the negotiations as part of the workers’ group, including sisters from Kenya and Zimbabwe who ensured gender-based violence remained the focus of discussions.

Violence and Harassment at Work Violates Basic Human Rights

The discussion included defining violence and harassment and assessing whether the final outcome should be a binding convention and a recommendation or only a recommendation.

Marie Clarke Walker, secretary-treasurer of the Canadian Labour Congress, represented the workers’ group. In committee negotiations among workers, employers and government representatives, Walker stated that violence and harassment at work constitutes a serious human rights violation, one that is incompatible with decent work, and one that impinges on the ability to exercise other fundamental labor rights.

Violence and harassment at work affect all occupations and sectors of the economy, including formal and informal work settings, Clark said. She also linked the importance of the negotiations to the current moment, including the #Metoo movement which has demonstrated the prevalence of violence and harassment at work and how it is both tolerated and endured, including by an especially high percentage of women seeking to obtain or maintain employment.

Walker also noted that while violence and harassment affects everyone at work, not everyone is affected in the same way nor on the same scale. Specifically, women and gender nonconforming people experience violence and harassment in disproportionate numbers, underlying the need for the gender dimensions of violence and harassment to be addressed in the instruments.

Countries Confirm Support for GBV at Work Convention

Representatives of several country members, including the European Union and its member states, confirmed their support for development of an effective ILO convention and emphasized that it must promote a gender-responsive approach, focus on prevention and enforcement measures, and improve protections for victims from intimidation and further assault.

The governments of African countries and Mexico also expressed support for a convention and recommendation. Speaking on behalf of the Africa group, the government of Uganda said a convention would leave no doubt about the international community’s commitment to influence domestic legislation.

Mexico’s representative observed that while both women and men were subject to harassment in the workplace, women were experiencing a higher vulnerability due to unfavorable labor market conditions. Further, international legal instruments should seek a general empowerment of women in the workplace, including with regard to sustainable development.

Employers do not want to see violence and harassment in the workplace, said Alana Matheson, the employer’s representative and deputy director of Workplace Relations at the Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry. Matheson noted that everyone has responsibilities for preventing violence and harassment as well as a right to work in an environment free from violence and harassment.

With the ILO’s final negotiations set for June 2019, workers, unions and our allies will be looking to build on the successes of this year’s committee meeting and negotiations to ensure the strong support by employers, member countries and workers for the need to prevent and address violence and harassment at work results in an inclusive convention and recommendation.

The final convention and recommendation must include a broad definition of violence and harassment, one that includes gender-based violence and an inclusive definition of worker and work where employers, member states and unions share obligations and responsibilities to prevent and address violence and harassment.

Robin Runge, Solidarity Center senior gender specialist, participated in the ILO conference.

Jun 28, 2018

Myanmar (Burma) and Turkmenistan do not meet minimum standards to address human trafficking and are making no attempts to do so, according to the 2018 U.S. State Department’s 2018 Trafficking in Persons Report released today. The report, which ranks countries based on their government’s efforts to comply with minimum U.S. Trafficking Victims and Protection Act (TVPA) standards, also boosted Uzbekistan from the bottom ranking to the Tier 2 Watch List.

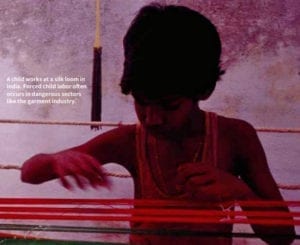

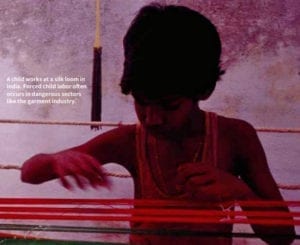

A child works at a silk loom in India. Credit: TIP report

The governments of both Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan annually force public employees and others to labor in the cotton fields. Although Uzbekistan recently has taken steps to end forced labor, the Uzbek government’s upgrade to the Tier 2 Watch List “is premature due to its persistence on a large scale—at least a third of a million people—in the last harvest,” says Bennett Freeman, former deputy assistant secretary of State, Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor and co-founder of the Cotton Campaign, a broad coalition working to end forced labor in the cotton fields.

Myanmar was downgraded this year from the Tier 2 Watch List, which requires, in part, that countries not fully meeting the TVPA’s minimum standards make significant efforts to do so.

The report also downgrades Malaysia from Tier 2 to the Tier 2 Watch List, addressing the country’s controversial upgrading in 2016 from the lowest ranking. Solidarity Center allies have documented extensive forced labor conditions in Malaysia. The Kyrgyz Republic and South Africa also were downgraded from Tier 2 to the Tier 2 Watch List, which includes countries like Bangladesh, Guatemala, Haiti, Iraq, Liberia, Nicaragua and Nigeria.

Thailand was upgraded from the Tier 2 Watch List to Tier 2.

Profits from forced labor account for $150 billion in illegal profits per year, according to the International Labor Organization (ILO).

The TVPA report organizes countries into tiers based on trafficking records: Tier 1 for nations that meet minimum U.S. standards; Tier 2 for those making significant efforts to meet those standards; Tier 2 “Watch List” for those that deserve special scrutiny; and Tier 3 for countries that are not making significant efforts.

The Trafficking in Persons report, which has been issued annually for 18 years, covers 190 countries and is required by the 2000 TVPA law.

Jun 21, 2018

Solidarity Center Africa Regional Program Director Imani-Countess and NDI’s Patrick Merloe discussed challenges to democratic transition in Zimbabwe. Credit: Solidarity Center/Shayna Greene

Wage theft and other forms of economic injustice are among the major factors holding Zimbabwe back from a democratic transition, says Imani Countess, Africa regional program director for the Solidarity Center.

Countess spoke at a recent panel discussion in Washington, D.C., “Assessing Zimbabwe’s Election and Prospects for a Democratic Transition,” organized by the National Endowment for Democracy (NED). Bringing a labor perspective to the event, Countess described the strong correlation between increased participation in unions and the formation of other democratic institutions.

“There’s absolutely a link between democratic structures, the nature of unions and the role they play in the workplace, and in the nation and the fostering of broader democratic participation, particularly in elections,” says Countess.

Undemocratic practices flourish when workers are trapped in a cycle of economic inequality. Countess gave the example of 200 Zimbabwean women who experienced this type pf hardship firsthand after their husbands had not been paid for five years by the Hwange Colliery Co. Ltd. (HCCL). The company is one of the biggest in Zimbabwe, with the government as its largest shareholder.

Despite exporting to 13 nations including South Africa and China, HCCL owed its workers $70 million in unpaid wages. Often, companies will try to look attractive to foreign investors with competitive prices by engaging in forced labor and wage theft, Countess says.

Company’s Wage Theft Forced Families Turned to Informal Economy

The wives of the HCCL workers first protested in 2013 and were attacked by police. When they began protests again in 2018, they were joined by the Center for Natural Resource Governance, the National Mine Workers Union of Zimbabwe (NMWUZ) and the Zimbabwe Congress of Trade Unions.

Although the mine workers are not union members, Zimbabwe unions stood by the women because they were “the wives of workers,” says Countess. “So the National Union of Mine Workers was there.”

To help feed their families, the women took on informal jobs such as selling in markets and cross-border trading. About 94 percent of Zimbabweans work in the informal economy. Of the 6 percent working permanent jobs, one-third are exposed to wage theft, especially in the extractive sector, says Countess.

“For five years, these women subsidized the Hwange Colliery Co. by supporting their husbands’ ability to work without pay,” she says.

Civil society groups helped mobilize the women in their campaign through workshops on nonviolent strategies for resistance and other skills-building strategies, and opportunities to exchange experiences with women in other mining communities.

Finally, demands were met, ensuring that the women’s husbands were paid and not retaliated against for the actions of their wives.

This is only one example of how unions promote democracy in Zimbabwe despite the country’s challenges, says Countess. Though Zimbabwe is a militarized state with an unenforced constitution, union members are active in community organizations and serve in national election observation groups. For instance, in 2013, unions came together representing 15 countries in the Southern Africa Trade Union Coordination Council (SATUCC) region to participate in an observation mission in Zimbabwe.

“Mass-based organizations working together with communities can be powerful actors of change,” says Countess.

Also on the panel were Patrick Merloe, senior associate and director for Electoral Programs at the National Democratic Institute, and Elizabeth Lewis, deputy director for Africa at the International Republican Institute.