Jul 27, 2017

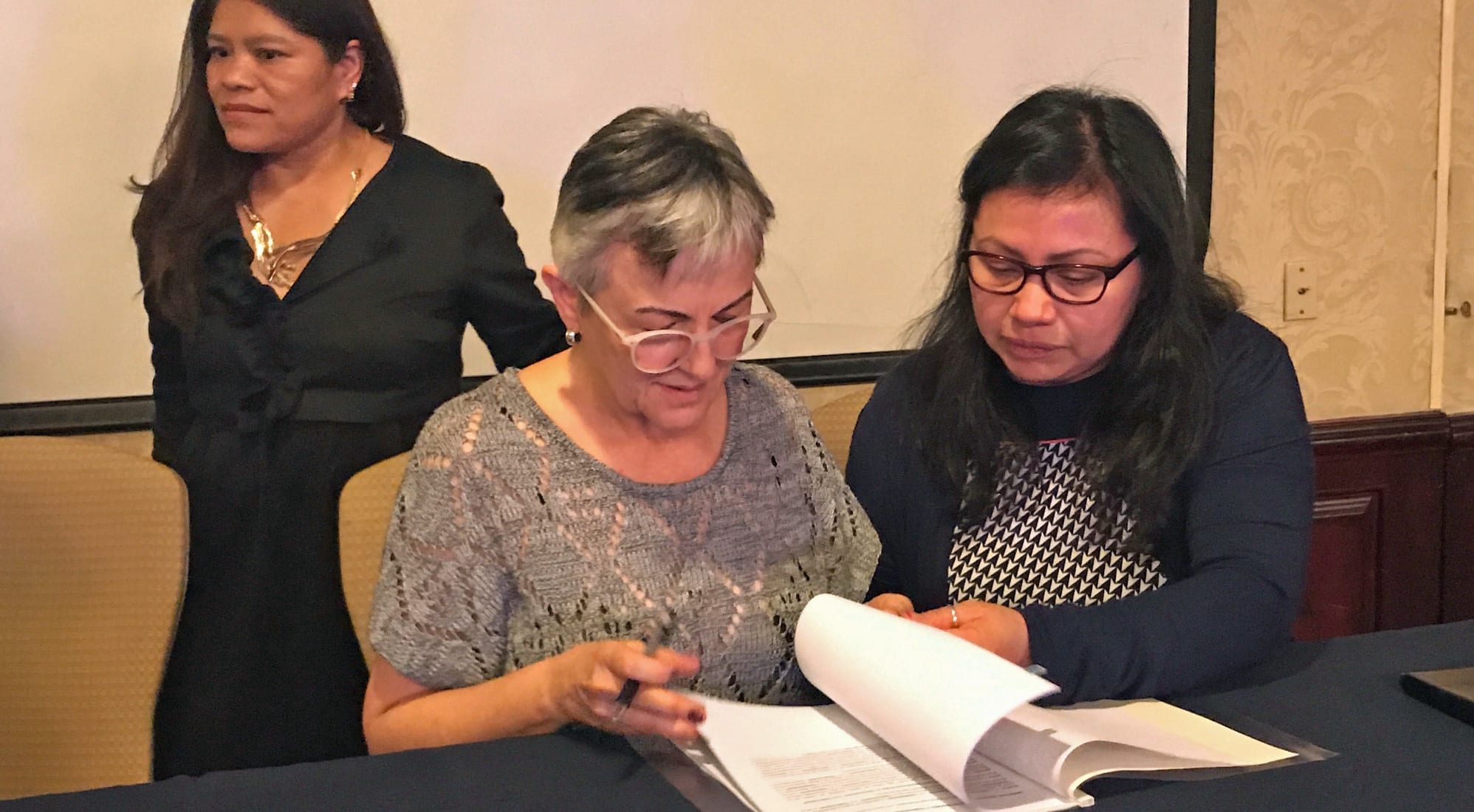

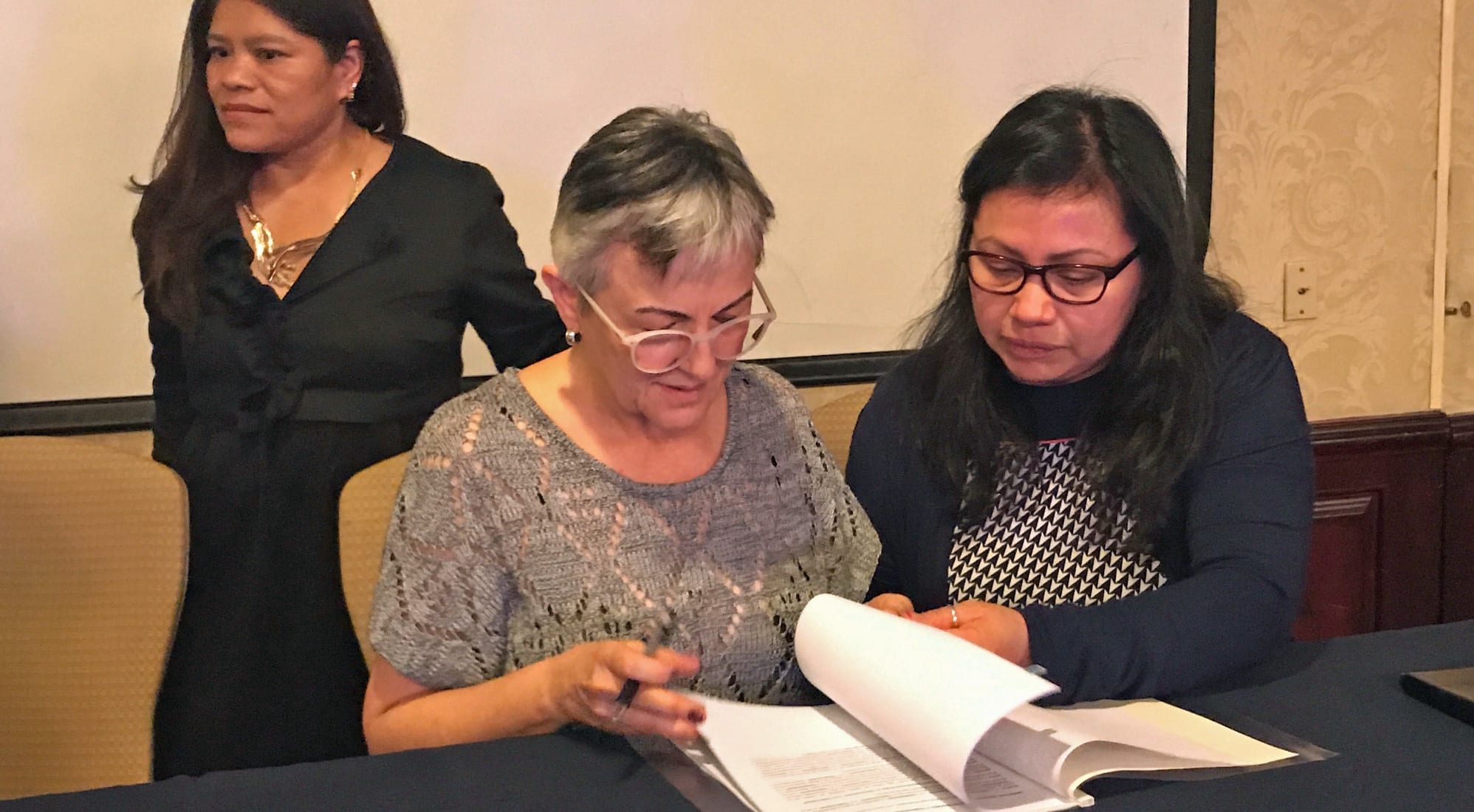

The Mexican domestic workers union, SINACTRAHO, last week launched a far-reaching campaign to ensure domestic workers across Mexico are covered by employment contracts.

“Our goal is to have 10,000 workers sign a formal contract with their employers, in time for December holidays,” says Marcelina Bautista, SINACTRAHO co-president.

“Trabajo Digno por Ti, por Mi y todas Mis Compañeras” (“Decent Work for You, for Me, and all My Sisters”) also is gaining unlikely support—from employers.

“This is not an act of kindess, this is an action of responsibility,” says Maite Azuela, speaking on behalf of “Hogar Justo Hogar” (Home, Just Home), a group of employers that aims to work jointly with workers to improve rights and labor conditions.

“The unjust conditions that exist in our country and in our workplaces, we as employers too often replicate at home,” she says. “Building the country that we truly want is work that begins at home.”

During the campaign launch June 23, which coincided with Mexico’s annual day to celebrate domestic work, the union presented two model contracts, one for domestic workers who labor full time for an employer, and another for part-time workers. The contracts include a calculation sheet to determine proper accrual and payment of benefits afforded to workers under law.

“I appreciate Marcelina´s work and support, and all the people here, because I am beginning to understand that there are people who support us,” says SINACTRAHO member Yazmin Méndez.

“I know that we can change the situation that we as workers live. Our work is the same as another job, we have rights and resposibilities.”

SINACTRAHO was founded two years ago and has since grown to some 900 members nationwide. The struggle by Mexico’s domestic workers for rights on the job is documented in the film, “Day Off” (Día de Descanso), in which SINACTRAHO executive board members take part.

Jul 27, 2017

In Mombasa, the labor broker’s announcement that jobs were available in Saudi Arabia resonated with Maria Makori Mwentenje.

“We were very poor. We had two children,” (age 10 and 1), Makori says, describing why she and her husband agreed that she should seek work in the Saudi Arabia. “We tried a small business and selling food, but that didn’t work. And there were no casual jobs available. We were hustling every day, but some days there was not enough to feed the family.”

Makori signed up with the labor broker but was not given a contract nor told her duties. Only at the airport did she learned she would be paid 18,000 Kenya shillings ($172) a month rather than the 23,000 ($221) she was promised. But even at that rate, she had to take a chance—it was not possible to earn that much in Kenya. She boarded the plane.

When she arrived in Saudi Arabia, she and other women traveling for work were taken to a room where their passports and travel documents were confiscated. Under the kefala system in Arab Gulf countries, migrant workers are tied to one employer, and it is illegal for them to get another job in the country. To ensure they do not leave, employers typically take their passports and often their mobile phones.

In Saudi Arabia, Makori was required to care for four children, including a baby. Working around the clock, her employer expected her to wake at all hours of the night to tend to the baby and still rise at 6 a.m. to prepare the family’s breakfast and get the children ready for school.

During her last pregnancy, Makori had developed hypertension, and in Saudi Arabia, the long hours, stress and difficult tasks exacerbated her condition. She experienced frequent headaches, and her body started to swell. Rather than take her to a doctor, her employer forced her to take pills, and she did not know what they were.

She was sexually harassed from the time she first walked into the employer’s house. When she contacted her husband and told him about the abuse, her husband went to the labor broker and asked why he sent his wife to such an employer. Rather than take steps to ensure Makori’s safety, the labor broker verbally abused her husband.

At one point, when she was too ill and tired to work, she told her employer she needed to rest. Enraged, the employer’s daughter entered the tiny space where Makori slept and after screaming at her, threw an iron at Makori, barely missing her head.

Fearing for her life, Makori fled to the police, where she was fortunate to encounter an officer who forced the family to return her passport and gave her money to travel. Unpaid for six months of work, she was grateful to return home with her life.

Jul 25, 2017

Update: On July 27, the Haitian government announced a slight minimum wage increase for garment workers that fall far below workers’ demands for a wage that would enable them to support their families. The minimum wage will rise by 81 cents a day, to $5.73. Union members plan to launch a week-long strike on Monday.

Thousands of garment workers in Haiti took to the streets this month to demand an increase in the sectorwide minimum wage that leaves most workers unable to cover bare necessities.

The current daily minimum wage is 300 Haitian gourdes, or $4.70. Garment workers are demanding that the minimum wage be increased to 800 gourdes, or about $12.70 a day. In 2014, before the devaluation of the Haitian currency and the onset of double-digit inflation, the Solidarity Center found that a real living wage for Haitian workers would be at least $23 a day.

This round of strikes is the latest in a series of demonstrations that began May 19 in the wake of a 30 percent spike in fuel costs, which resulted in dramatic increases to food and transportation expenses for workers. Striking workers are also calling for health benefits and food and transportation subsidies.

Unions are calling on employers to respect workers’ rights to freedom of association, citing numerous instances when workers who tried to form organizations to represent their interests were terminated, threatened or blacklisted. Approximately 45 union leaders from GOSTTRA who were fired in the midst of the May demonstrations remain out of work.

The tripartite Superior Council of Wages (CSS), which includes only two labor representatives and is tasked with providing Haiti’s executive branch with a recommendation for wage increases, issued its latest report on July 10. In the report, the CSS recommends that the daily minimum wage increase a mere 35 gourdes, or 55 cents, citing the need to keep Haiti competitive as the nation seeks to attract more employers in the sector.

Workers are, not surprisingly, outraged by the recommendation of the CSS. They also disagree with the suggestion that the wage increase be implemented in August without retroactive pay to May, as has been the custom in prior years.

Employer representatives, namely the Association of Industries of Haiti (ADIH), have continued to express a desire to offer only minimal wage increases to keep Haiti as a low-wage destination for global brands. In late June, six companies wrote to Prime Minister Jack Guy Lafontant to demand that the government intervene and quell worker protests related to the minimum wage. As the situation continues to escalate, the focus shifts to President Jovenel Moise and the executive branch. The presidential decree on the minimum wage is expected to be released in the near future.

Jul 25, 2017

“Why does being low-wage and a migrant mean being sentenced to a lifetime of being separated from your family? It shouldn’t and doesn’t have to,” says Solidarity Center Executive Director Shawna Bader-Blau. Speaking at a United Nations meeting on migration today in New York, Bader-Blau contrasted the unchallenged right of capital to move freely across borders with the lack of rights and labor protections for migrant workers.

Being low-wage and a migrant should not mean being sentenced to a lifetime of being separated from your family–Solidarity Center Executive Director Shawna Bader-Blau Credit: Solidarity Center/Neha Misra

“We have not seen a commensurate expansion of the rights of people to go along with the incredible expansion of the rights of business, especially not for the migrant workforce. If we want to talk about the human rights of migrants, we really need to directly challenge those assumptions.”

Bader-Blau addressed the Fourth Thematic Event, “Contributions of Migrants and Diaspora to all Dimensions of Sustainable Development, including Remittances and Portability of Earned Benefits.” The July 23–25 meeting is among six thematic sessions held between April 2017 and November 2017 to gather substantive input and concrete recommendations to inform the development of the UN Global Compact on Migration.

Migrant Workers Should Be Free to Bargain with Employers

Neha Misa, Solidarity Center migration and human trafficking senior specialist, also spoke at the consultation, where she asked participants to “imagine if migrant workers could fully participate in the right to organize and collectively bargain.”

“We have seen time and time again how collective bargaining agreements provide migrant workers with the ability to earn a decent wage, and they may even be used to lower the costs of recruitment and provide migrant workers with more safe and secure ways to remit their earnings back home. Collective bargaining agreements also help to protect women migrant workers from gender-based violence and other forms of discrimination in the workplace.”

Misra, who also presented on behalf of the Women in Global Migration Network (WIMN), says “women in migration are not ‘vulnerable,’ in need of ‘rescue’—they are advocates for their rights and agents of change.” Current migration policies must be changed from being about ‘protecting women’ to ‘protecting women’s rights,’ she says.

The Solidarity Center is a member of WIMN and the Global Coalition on Migration, both of which took a strong role at the session.

Misra detailed a list of recommendations for inclusion in the UN Global Compact, including embedding core labor and human rights standards. (Read her full statement and recommendations here.)

Many workers migrate for jobs because none exist in their home countries—Jonatan Monge Loría, chief coordinator of CI-Regional. Credit: Solidarity Center/Neha Misra

Addressing labor migration also means attending to the conditions that foster this phenomenon from origin countries, says Jonatan Monge Loría, chief coordinator of the Central American Regional Inter-Union Committee for the Defense of the Migrant Workers Rights (CI-Regional).

“Many dependent economies lack productive development policies that generate the quantity and quality of jobs that are required for decent work and livelihoods that sustain families,” says Loría. “It is no secret that poor development conditions and lack of job opportunities in origin countries are the trigger for this type of migration.”

Loría spoke on behalf of CI-Regional, a Solidarity Center partner, and the Trade Union Confederation of the Americas (TUCA/CSA) and the Trade Union Council for Technical Assistance. (See Loría’s full remarks in English and Spanish.)

‘Borders Are Not Exempt from Human Rights’

At the Third Thematic Event last month in Geneva, Asia Region Director Tim Ryan addressed the issue of governance of migration, saying “it is dangerous to think borders can be hermetically controlled, and borders are not exempt from human rights.

“Governments must move beyond an emphasis on temporary migration programs that restrict workers’ ability to exercise their rights—from freedom of association and voting rights to family unification—to regular migration programs that allow for visa portability, the ability to change employers, exercising political and social rights, freedom of movement, family unity and pathways to residency and citizenship in destination countries.” (Read Ryan’s full statement here.)

Jul 25, 2017

The recent murder of a retired Guatemalan farmer and the violent attack against two others while holding a peaceful protest at their former employer, the San Gregorio Piedra Parada Farm, revealed a decades-long failure by the agribusiness to pay into the country’s social protection fund—shorting workers some 1.2 billion quetzals ($165,270).

Eugenio López, 72, was murdered at the farm of his former employer during a peaceful gathering of senior citizens seeking unpaid pension benefits. Credit: Courtesy, Comité de Unidad Campesina

Eugenio López, 72, was murdered June 23 and two others injured when they were fired upon during a peaceful gathering of mostly senior citizens who have been unable to receive their health and pension benefits from the Guatemalan Social Security Institute (IGSS) because San Gregorio has not paid into the fund since 1998, even though it deducted workers’ contributions to the fund.

The protest was spearheaded by the United Committee of Rural Farmers (Comité de Unidad Campesina, CUC) which has been fighting for the retirement benefits of 240 retired workers at the farm, 16 miles outside Coatepeque. Union leaders say other agricultural employers also withhold payment for workers’ retirement.

No one has been charged with the murder. Few murders of Guatemalan union leaders and members are resolved. The International Labor Organization is holding hearings on the assassination of 84 trade unionists in Guatemala, most with impunity. The Guatemalan government maintains that none of the 84 union murders are related to their union activity.

Guatemala is one of the most dangerous places in the world for worker rights activists, with 51 incidents of anti-union violence documented and verified in between 2015 and 2016, and five incidents so far in 2017, according to a report by the Worker Rights Defenders Network of Guatemala.

The network condemned the murder and its statement is supported by a range of labor rights and other human rights groups, including: the National Council of Displaced Persons of Guatemala, the Mayan and Rural Farmer Organization, Nim Ajpu Association of Mayan Lawyers and Notaries and the Social and Popular Assembly and the Women’s Political Alliance.

The World Organization Against Torture (OMCT), the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH) and others issued statements and sent letters to the Guatemalan government in response to the Guatemalan union network and its allies call for support and advocacy.