Around the world, farmworkers typically are not covered by labor laws and are prevented from exercising their fundamental legal rights, namely to form unions and bargain collectively, says Jeff Vogt, director of Rule of Law for the Solidarity Center.

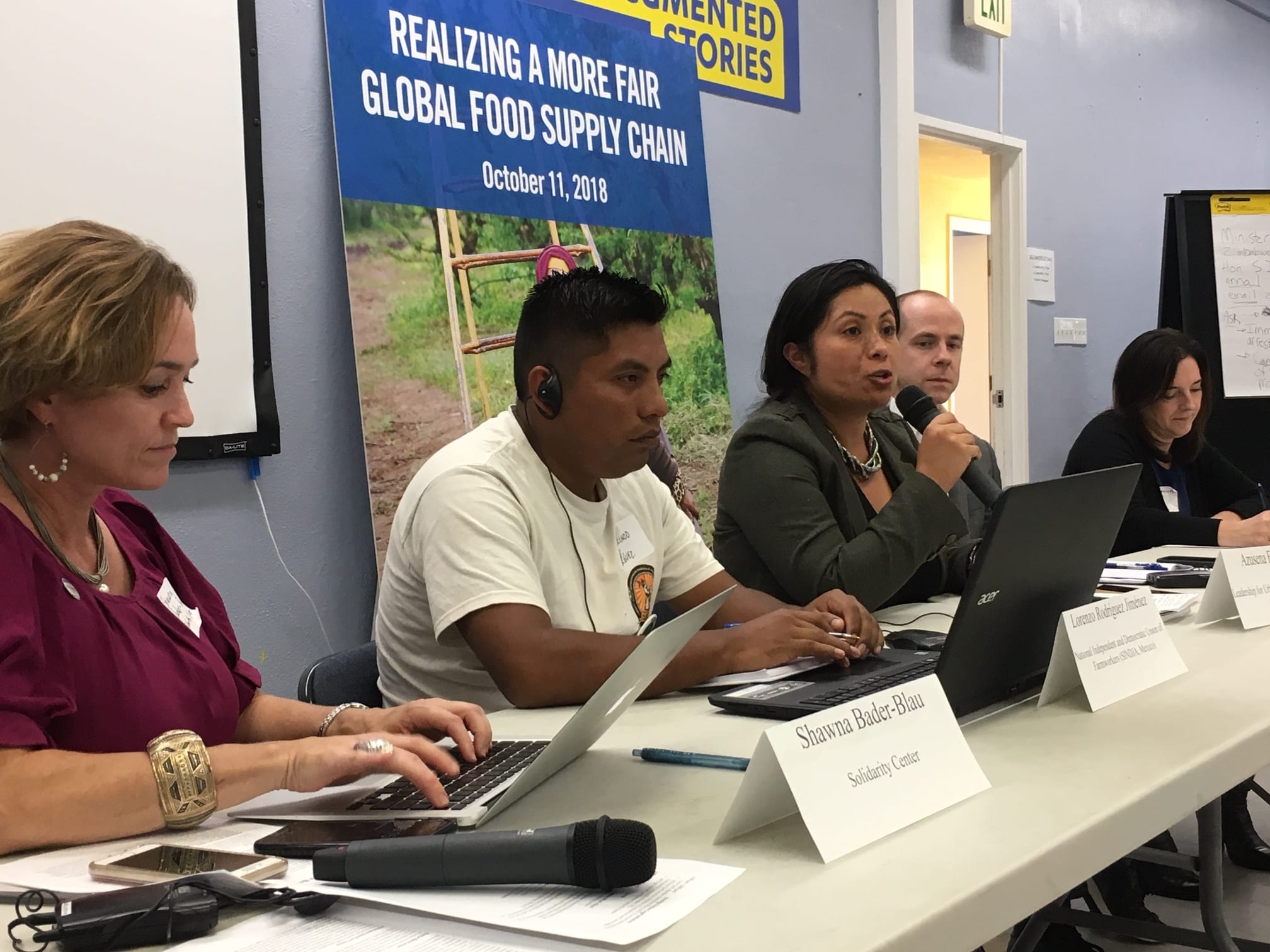

Vogt opened a panel on strategies for achieving legal justice for workers in the global food chain, launching the second half of the all-day conference, “Realizing a More Fair Global Food Supply Chain.”

Sponsored by the Solidarity Center, the Food Chain Workers Alliance and UCLA Labor Center, the event gathered farm worker activists and food justice advocates in Los Angeles to share strategies to build worker power, create decent work in the fields and demand greater justice across global food chains.

One-third of workers around the world labor in agricultural supply chains—planting, harvesting, transporting goods, retail—yet wages are a small fraction of what it costs to bring food to your table, says Vogt.

In Tunisia, where 61 percent of farmworkers are low-wage, temporary employees with no job security, the Tunisian federation of labor (UGTT) waged a nationwide campaign to cover farmworkers in labor laws.

Beginning in 2014, the UGTT negotiated a collective framework agreement with the government and employers that regulates safety and health, provides social protections, and guarantees the basic rights of labor.

The UGTT’s advocacy campaign is now engaging workers to inform them about their new rights. “It is a long fight that we will continue until we get the victory for all workers,” says Tahri, speaking through a translator.

Across the globe in Los Angeles, Food and Commercial Workers union (UFCW) Local 770 is working on living wage initiatives to raise the minimum wage and paid sick leave, and has launched an apprenticeship programs for meat cutters it hopes to expand to other food workers.

Throughout, the union is educating workers on their rights on the job, says UFCW Local 770 President John Grant. “We view workplaces, especially union workplaces as places where workers put forward their voice for what’s important,” he says.

“In the community, you have voice in deciding, for example, whether there will be a park. But without a union, you don’t have democracy in the workplace to decide what’s going on,” Grant says.

Agnieszka Fryszman, a law partner at Cohen, Milstein, discussed three cases that utilized the U.S. Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act (TVPRA) to see justice for workers trafficked in food supply chains.

One involves rural Cambodian villagers who say they were trafficked for forced labor in the shrimp processing industry in Thailand. A coalition led by the Solidarity Center, filed an amicus brief on June 1 in support of the seven workers who had brought their suit based in part under the TVPRA, which in 2008 was amended to extend civil liability to those who “knowingly benefit” from the trafficking of persons in their supply chains.

Adrienne DerVartanian, director of the Washington, D.C.-based Immigration and Labor Rights, Farmworker Justice, noted the importance of educating lawmakers about challenges farmworkers face and empowering women farmworkers who are especially vulnerable to physical and sexual abuse in the fields.

As participants discussed how to go forward, Solidarity Center Executive Director Shawna Bader-Blau says when we talk about taking the next step for food workers, “we are talking about unstoppable forces against repression, be they government or be they corporations.”

“Our approach is to challenge systems and create access to capital,” says Azusena Favela, director of programs and operations, Leadership for Urban Renewal Network (LURN). Working with the 50,000 street vendors across Los Angeles, LURN piloted a loan program for vendors to access the resources they need to improve their own economic conditions while championing laws that enable vendors to freely operate.

“The biggest misconception is that street vendors choose to do this. Most times its not a choice. It’s basic survival many times,” she says, describing the long hours involved beginning with procuring goods to sell for long hours throughout the day.

“We understand that if it were not for street vending, street vendors probably would not have opportunity to survive in a city as expensive as LA.”

Rusty Hicks, president of the Los Angeles County Federation of Labor, described an array of efforts that include campaigns for an increase in the minimum wage and ensuring the law is enforced.

“Our goal is to get everyone the benefit of a union and fight for every worker the same as if they had a collective bargaining agreement,” Hicks says.

Lorenzo Rodríguez Jiménez, general secretary of the National Independent and Democratic Union of Farmworkers (SINDJA) in Mexico, discussed the struggle to form a union of farmworkers in an environment in which many unions are government-backed and not run in the interest of workers.

Sarah Gammage, director of gender, economic empowerment and livelihoods at the International Center for Research on Women (ICRW), emphasized that it is “really important to remind us of the importance of organizing” a theme echoed throughout the day, as worker advocates and their food justice allies began building on their mutual strength and vision across global borders.