In Thailand, Burmese Migrant Workers Toil Without Rights

An estimated 200,000 Burmese migrants fuel Thailand’s huge fishing industry in Samut Sakhon province, an hour outside of Bangkok. The majority of workers are ethnic Mon from farming villages in southern Burma and they send their salaries to their families back home. Many workers do not hold legal documents and are vulnerable to exploitation by traffickers and lack access to legal protection.

Dockworkers at the Pae Pla Pier in Mahachai, Thailand, known as “Little Burma,” earn between 300 to 600 Thai baht ($9–$18) per day for carting barrels of fish from the fishing trawlers and loading on to seafood trucks.

Others work in factories, most in the large fish canning factory Unicord, where 6,000 workers labor each day over two shifts.

The Human Rights Development Foundation (HRDF), a local nongovernmental organization staffed in part by former migrant workers, provides legal, human rights and social support for Burmese migrant workers in Mahachai.

Naing Lin, 27, is among them. One of five siblings from a low-income farming family, Lin entered Thailand in 2007 to earn better wages to help support his family. In 2009, he lost his hand in a machine accident at a plastics factory. The factory owner provided no compensation. HRDF filed a suit with the employer seeking compensation, a year-long process during which HRDF provided Lin with free housing. Ultimately, Lin received approximately $3,000.

He now earns roughly $10 a day delivering sacks of rice. He sent a third of the compensation funds to his family in Burma and spent another third to buy a passport and a pay for a work permit, hoping to find a better-paying job.

In Thailand, the Solidarity Center helps migrant workers learn about and exercise their rights by supporting local resource centers such as HRDF and the Burmese-led Migrant Worker Rights Network (MWRN). Through field staff, MWRN and HRDF can communicate with and build trust with migrant workers to encourage them to protect and enforce their rights. Migrant workers are often afraid to bring up job safety issues, forced labor or trafficking.

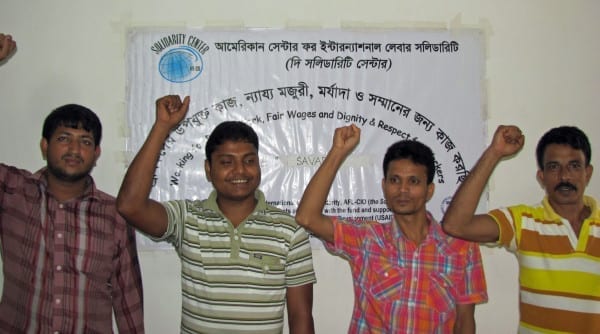

Although migrant workers are denied the basic freedom of association in Thailand, the Solidarity Center helps them form informal trade union networks and connects them with union allies, enabling them to organize, lead, represent and protect themselves from trafficking and abuse—an important part of empowering migrant workers.

An estimated 200,000 Burmese migrants fuel Thailand’s huge fishing industry in Samut Sakhon province, an hour outside of Bangkok. Credit: Solidarity Center/Jeanne Hallacy

At the Pae Pla Pier in Mahachai, Thailand, Burmese dockworkers cart barrels of fish from trawlers to seafood trucks. Credit: Solidarity Center/Jeanne Hallacy

Burmese dockworkers in Thailand are paid between $9 and $18 a day. Credit: Solidarity Center/Jeanne Hallacy

Like many migrant workers around the world, migrants in Thailand have no job safety protection or access to other worker rights. Credit: Solidarity Center/Jeanne Hallacy

Many factories in Thailand depend upon migrant workers, with one fish cannery alone employing 6,000 workers. Credit: Solidarity Center/Jeanne Hallacy

A Burmese migrant worker outside the fish canning factory where she works. Credit: Solidarity Center/Jeanne Hallacy

Tens of thousands of migrants from Burma work in Thailand’s fish canneries. Credit: Solidarity Center/Jeanne Hallacy

During an HRDF training at a worker’s house, Nang San Mon (left) and Sai Sai, (right) a volunteer with Migrant Workers Rights Network, describe to newly arrived migrants the process of registering for work permits. Credit: Solidarity Center/Jeanne Hallacy

HRDF assisted Naing Lin, a Burmese migrant worker, in getting worker compensation after he lost his hand while working at a plastics factory. Credit: Solidarity Center/Jeanne Hallacy

The Solidarity Center supports local resource centers such as HRDF and MWRN in Thailand that assist migrant workers and their families. Credit: Solidarity Center/Jeanne Hallacy