Domestic workers—at great risk during the pandemic crisis—are mobilizing to secure rapid relief and protection says the International Domestic Workers Federation (IDWF). This International Domestic Workers Day, more than 60 million of the world’s estimated 67 million domestic workers, most of whom are women of color working in the informal economy, are facing the pandemic without the social supports and labor law protections afforded to workers in formal employment. And, during a period of heightened infection risk, tens of thousands of migrant domestic workers are being forced to live in their employers’ homes, housed in crowded detention camps or have been sent home where there are no jobs to sustain them or their families.

The health and economic risks to domestic workers during the pandemic and compulsory national lockdowns are high. At the margins of society in many countries, most domestic workers are excluded from national labor law protections that require employers to provide paid sick leave and mitigate workplace infection risks through provision of adequate personal protective equipment (PPE) and appropriate social-distancing measures. And, if they get sick, many domestic workers cannot access national health insurance schemes.

“Domestic workers are among those most exposed to the risks of contracting COVID-19. They use public transport, are in regular contact with others… and don’t have the option of working from home, especially daily maids,” says Brazil’s national union of domestic workers, FENETRAD.

Without adequate personal savings due to poverty wages, many domestic workers and their families are suffering food insecurity because of income interruption or job loss.

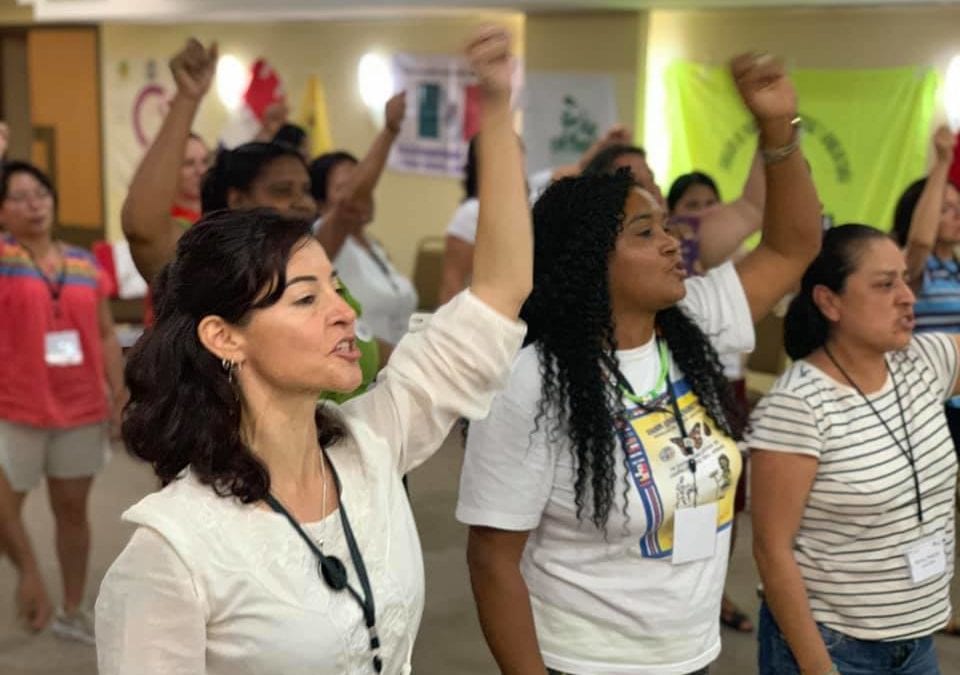

“We can’t have many domestic workers left out in the cold,” says Myrtle Witbooi, founding member and first president of IDWF, and general secretary of the South African Domestic Service and Allied Workers Union (SADSAWU).

“Let us shout out to the world: We are workers!” she says.

Domestic workers have long shared their experiences with the Solidarity Center, detailing their long working hours, poverty wages and violence and sexual abuse. During the pandemic, additional sources of economic peril and health risks are being reported, including:

- In Mexico, where 2.2 million women are domestic workers, most of them are being dismissed without compensation. In a recent survey of domestic workers, the national domestic workers union SINACTRAHO found that 43 percent of those surveyed suffered a chronic condition like diabetes or hypertension, increasing their vulnerability to COVID-19.

- The United Domestic Workers of South Africa says their members report that some employers refused to pay wages during the country’s compulsory lockdown unless staff agreed to shelter in place with their employer, and that domestic workers who could not report to work were not paid.

- In Asia, women performing care work were excluded when countries launched COVID-19 responses and stimulus packages, says Oxfam.

- In the Latin American region, where millions of people who labor in informal jobs rely on each day’s income to meet that day’s needs, the pandemic lockdown is causing an economic and social crisis.

- Globally, unemployment has become as threatening as the virus itself for the world’s domestic workers, reported the ILO in May.

Meanwhile, migrant domestic workers—who often leave behind their own children to care for others to support their own families back home—are in peril. Some are being sent home without pay, some are subject to wage theft. Others are being quarantined by the thousands in dangerously crowded conditions or in lockdown in countries where they do not speak the language and have little access to health care, local pandemic relief or justice. For example:

- Thousands of Ethiopian domestic workers are stranded in Lebanon by the coronavirus crisis.

- At least one-third of the 75,000 migrant domestic in Jordan had lost their incomes and, in some cases, their jobs only one month into the pandemic.

- For millions of Asian and African migrant domestic workers in the Middle East, governments restrictions on movement to counter the spread of COVID-19 increased the risk of abuse, reports Human Rights Watch.

- Several Gulf states are demanding that India and other South Asian countries take back hundreds of thousands of their citizens. Some 22,900 people were repatriated from the UAE by late April, many without receiving wages for work already performed.

On June 16, International Domestic Workers Day, we honor the majority women who perform vital care work for others. Every day, and especially during the pandemic, the Solidarity Center is committed to supporting the organizations that are helping domestic workers attain safe and healthy workplaces, family-supporting wages, dignity on the job and greater equity at work and in their community.

“International Domestic Workers Day is a great opportunity to talk about power and resistance, and how we survive now and build tomorrow,” says Solidarity Center Executive Director, Shawna Bader-Blau, who applauds actions by all organizations dedicated to supporting and protecting domestic workers during the pandemic. These include:

- Domestic workers who are leaning into organizing and advocacy efforts during the pandemic, including in Peru, where they won the right to a minimum wage and written contracts by challenging the constitutionality of failing to implement the ILO domestic workers convention after ratification; in the Dominican Republic, where they mobilized to register 20,000 domestic workers into the social security system and lobbied for their inclusion in government aid, gaining new members in the process; in Brazil, where they successfully fought to remove domestic workers from the list of “essential workers” to limit their exposure to COVID-19 because of their limited safety net.

- In Bangladesh, BOMSA, a migrant rights nongovernmental organization (NGO), is creating and distributing COVID-19 awareness-raising leaflets specifically for migrant domestic workers returning to Bangladesh from abroad. Members are distributing soap, disinfectant and other cleaning supplies, and encouraging workers to maintain social distance. Another migrant rights NGO, WARBE-DF, is distributing COVID-19 awareness-raising leaflets to returned migrant workers and their communities. And as thousands of migrant workers return, the organization is engaging in local government coronavirus response committees to ensure inclusion of migrant-specific responses. Both are longtime Solidarity Center partners.

- Also in Bangladesh, in Konbari area—where garment workers who are internal migrants are not eligible for relief aid as it relies on voting lists for relief distribution—the local Solidarity Center-supported worker community center is connecting with local government officials and has provided nearly 200 names for relief, and is fielding more calls from internal migrant workers seeking assistance.

- In Brazil, which has more domestic workers than any other country—over 7 million—the National Federation of Domestic Workers (FENETRAD) and Themis (Gender, Justice and Human Rights) started a campaign calling for domestic workers to be suspended with pay while the risk of infection continues, or to be given the tools to protect against risk, including masks and hand-sanitizing gel.

- Also in Brazil, FENATRAD is providing legal and other advice by phone to domestic workers and delivering relief packages of food, medicines and protective gear, including masks, clothing, soap and hand sanitizer, to union members and their families.

- In the Dominican Republic, three organizations representing domestic workers successfully advocated with the Ministry of Labor for domestic workers’ to be included in the country’s COVID-19 relief program.

- In Mexico, to raise awareness and make the sector more visible, SINACTRAHO collected WhatsApp domestic worker audio messages about their experiences during the crisis for sharing on a podcast.

- The Alliance Against Violence & Harassment in Jordan, a Solidarity Center partner, is urging the government to grant assistance to migrant workers, who have little or no pay but cannot return to their country. The Domestic Workers’ Solidarity Network in Jordan shares information on COVID-19 and its impact on workers in multiple languages on its Facebook page

- The Kuwait Trade Union Federation urged the government to address the basic needs of Sri Lankan migrant workers, many of whom were domestic workers trapped in Kuwait after Sri Lanka closed its borders on March 19. Workers were eventually housed in 12 shelters while travel arrangements home were made.

- In Qatar, Solidarity Center partners Migrant-Rights.org and IDWF in April helped launch an SMS messaging service in 12 languages to provide tips to migrant domestic workers on COVID-19 and how to protect their rights.

- In South Africa—where many domestic workers suffer deaths and crippling injuries without compensation because they are excluded from the country’s occupational injuries and diseases act (“COIDA”), according to a recent Solidarity Center report—trade unions are demanding that employers provide their domestic workers with adequate PPE.

The Solidarity Center has joined its partners, the Women in Migration Network (WIMN) and a coalition led by the Migrant Forum in Asia, in urging governments and employers to uphold the rights of migrant workers, including migrant domestic workers.

Without urgent action to provide relief to workers in informal employment, including those providing domestic work, quarantine threatens to increase relative poverty levels in low-income countries by as much as 56 percentage points according to a new brief from the UN’s International Labor Organization (ILO).