Some 34 million Africans are migrants, and the majority are workers moving across borders to search for decent work—jobs that pay a living wage, offer safe working conditions and fair treatment.

Yet even as they often leave their families in search of jobs that will support them, many migrant workers find that employers seek to exploit them—refusing to pay their wages, forcing them to work long hours for little or no pay, and even physically abusing them.

Throughout the January 25-27 Solidarity Center Fair Labor Migration conference in Johannesburg, South Africa, migrant domestic workers, farm workers and mine workers share their struggles, but also their courage and hope as many join together to form unions and associations to improve their lives at work. Here are their stories.

Fauzia Muthoni Wanjiru left Kenya after a labor broker told her she would work in Qatar as a receptionist. Instead, she was taken to Saudi Arabia, where she was forced to work 18 hours a day as a domestic worker cleaning two homes a day. Her passport was taken, trapping her in the country. “When you go there, you are a slave to them,” she says.

Praxedes moved from Zimbabwe to South Africa so her children would live a better life than she had. “There is nothing for me there (in Zimbabwe), she says. “A lot of employers take advantage of that.” She has worked for more than five years as a domestic worker, and employers have refused to pay her overtime, and shortchanged her pay—even as her transportation costs take up a third of her wages. “My cellphone has to be off at all times. I have three kids. If anything happens to them, I will not know.”

Angela Mpofu migrated from Zimbabwe to support herself and her family as a domestic worker in South Africa. But like many migrant workers, she finds that she is treated poorly, as employers take advantage of her migrant status. Worse, says Mpofu, “the way (employers) treat us, it’s like we are not human beings. You’re nothing to them.”

As a migrant mine worker from Swaziland, Mduduzi Thabethe says he has fewer workplace rights than his South African co-workers. Although all mine workers pay the same amount into the health fund, migrant workers get inferior care and pensions are rare. “If you are a citizen of South Africa, you see you are building your country and you have something, but we have nothing.” His union, the Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union, is working to improve conditions for migrant workers.

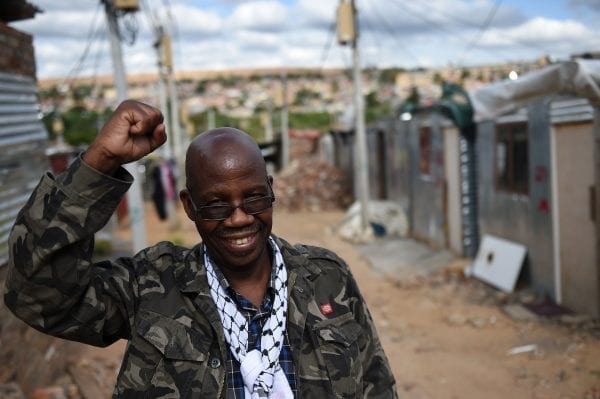

When Joe Montisetse came to South Africa from Botswana to work in gold mines in the early 1980s, he saw a black pool of water deep in a mine that signified deadly methane. Yet after he brought up the issue to supervisors, they insisted he continue working, but Montisetse refused. Two co-workers were killed a few hours later when the methane exploded. Today, with the National Union of Mineworkers, Montisete, deputy president of the union, says workers are safer now. “We formed union as mine workers to defend against oppression and exploitiation,” says Montisetse.

In 2000, Chris Muwani migrated from Zimbabwe to South Africa, where he works on a tomato farm. If he does not fulfill his daily quota, he is not paid for the day. Migrant farm workers like Muwani are exposed to dangerous workplace conditions and without a union, cannot exercise their rights. “We use a chemical to spray grass but you don’t have rubber boots or a respirator but you are working with poison,” says Muwani. “If you protest about safety conditions, many people are fired.”

As a migrant farm worker from Mozambique, France Mnyike receives no health care coverage, even for workplace injuries. When Mnyike broke his leg at work, his employer did not provide medical aid and his leg remains fractured. Even if his workplace offered emergency care, says Mnyike, the employer would “deduct the cost from your salary.”