Imagine the population of New York City. Then triple that number. That’s how many people around the world are being robbed of their freedom through human trafficking—24.9 million.

While “trafficking” seems to imply movement across borders, some 77 percent of those targeted by human traffickers do not leave their country of residence, according to the International Labor Organization (ILO). Most are trafficked for forced labor, one-third are children.

Solidarity Center’s Neha Misra testified on Capital Hill on the need for worker rights in forming unions and bargaining as key to ending human trafficking. Credit: Solidarity Center/Tula Connell

“Human trafficking thrives in a context of private actors and economic coercion,” says Neha Misra, testifying recently on Capitol Hill before the Tom Lantos Human Rights Commission in a House Foreign Relations Committee hearing.

“We must address what one leading global expert on the international law of human trafficking calls the ‘underlying structures that perpetuate and reward exploitation, including a global economy that relies heavily on exploitation of poor people’s labor to maintain growth and a global migration system that entrenches vulnerability and contributes directly to trafficking,’ ” says Misra, Solidarity Center senior specialist for migration and human trafficking. Trafficking and severe labor exploitation are part of a continuum of labor exploitation and abusive working conditions workers face around the world in workplaces as diverse as factories, farms and offices.

The Lantos hearing was part of a series of congressional events in January around U.S. Human Trafficking Awareness Month, which marks the date Congress passed the Trafficking Victims Protection Act (TVPA) in 2000. That same year, the United Nations passed the Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children (the Palermo Protocol). As part of the TVPA, the U.S. State Department each year issues a detailed report on trafficking in persons, ranking countries on the extent to which they are addressing and eliminating it.

Since then, global nations have a clearer understanding of human trafficking—including its direct connection to forced labor and exploitation—and 168 governments have implemented domestic legislation criminalizing all forms of human trafficking, transnationally and nationally.

Yet as indicated by the staggering number of those trafficked, much more needs to be done.

“Over the past 20 years, the extent of forced labor in global supply chains has become increasingly clear. And yet, governments continue to fail to hold corporations to account,” says Misra.

Migrant Workers, Domestic Workers Targets of Trafficking

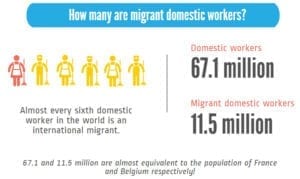

Isolated in private homes, domestic workers, whether nationals or migrants, are particularly at risk of exploitation, harassment and abuse, including sexual violence—and have difficulty accessing justice. Domestic workers, who comprise 11.5 million migrant workers—are also among the largest group of trafficked migrant workers and are vulnerable to human trafficking and forced labor—within their home countries, as internal migrants, and as cross-border migrants.

Isolated in private homes, domestic workers, whether nationals or migrants, are particularly at risk of exploitation, harassment and abuse, including sexual violence—and have difficulty accessing justice. Domestic workers, who comprise 11.5 million migrant workers—are also among the largest group of trafficked migrant workers and are vulnerable to human trafficking and forced labor—within their home countries, as internal migrants, and as cross-border migrants.

“Recognizing domestic workers as workers is key to combatting the vulnerability they face to human trafficking,” says Alexis De Simone, Solidarity Center senior program officer for the Americas. De Simone spoke at a Capitol Hill briefing Friday sponsored by U.S. Rep. Pramila Jayapal.

A domestic worker who requested anonymity described at the briefing the abusive conditions she experienced after a diplomat brought her from Chile to the United States in 2009. She was promised fair wages and benefits, but after she started working, the family refused to pay her. Her employers withheld food, stole her passport, and threatened her with deportation if she talked with anyone outside the household—an all-too common experience for domestic workers worldwide.

Collective Action Key to Ending Trafficking, Forced Labor

Combating human trafficking, forced labor and other forms of severe labor exploitation means putting worker rights at the forefront of solutions.

The 2011 ILO convention (global treaty) covering domestic workers “has raised the bar globally for states and employers to recognize and enforce the labor rights of domestic workers,” says De Simone.

Domestic workers around the world educated and mobilized for passage of the ILO Convention on Domestic Workers, along the way helping workers understand that violence, abuse, coercion and intimidation are not part of the job. “And that recognition, that righteous indignation, is often the spark for organizing that helps us end the imbalance of power,” says De Simone.

“Recognizing domestic workers as workers is key to combatting the vulnerability they face to human trafficking”—Alexis De Simone, Solidarity Center. Credit: Solidarity Center/Tula Connell

Yet not only international law, but on-the-ground grassroots union organizing and building power among domestic workers is key to combating vulnerability to trafficking, she says. “Union contracts are helping domestic workers worldwide ensure their rights to safe jobs without forced labor and human trafficking.”

De Simone cited examples of how union collective bargaining agreements have improved conditions for domestic workers in Argentina, Uruguay and Sao Paulo, Brazil, and shared the success of domestic workers in Mexico who ensured the country’s new labor law includes domestic workers—often among an excluded group of workers in many country’s labor laws.

Unions also are reaching across borders, building union-to-union relationships between countries of origin and destination like Paraguay and Argentina, Nicaragua and Costa Rica, Nepal and Lebanon.

But “freedom of association must be assured in practice, not just law,” says Misra. “This means strict penalties for employers who fire, retaliate against or collude with government officials to deport migrant workers seeking to form unions.”

Says Misra: “From rubber plantations in Liberia, garment factories in Jordan and to domestic workers’ households in Kenya, Solidarity Center has seen time and again how democratic worker organizing and collective bargaining can eliminate forced labor in a workplace.”