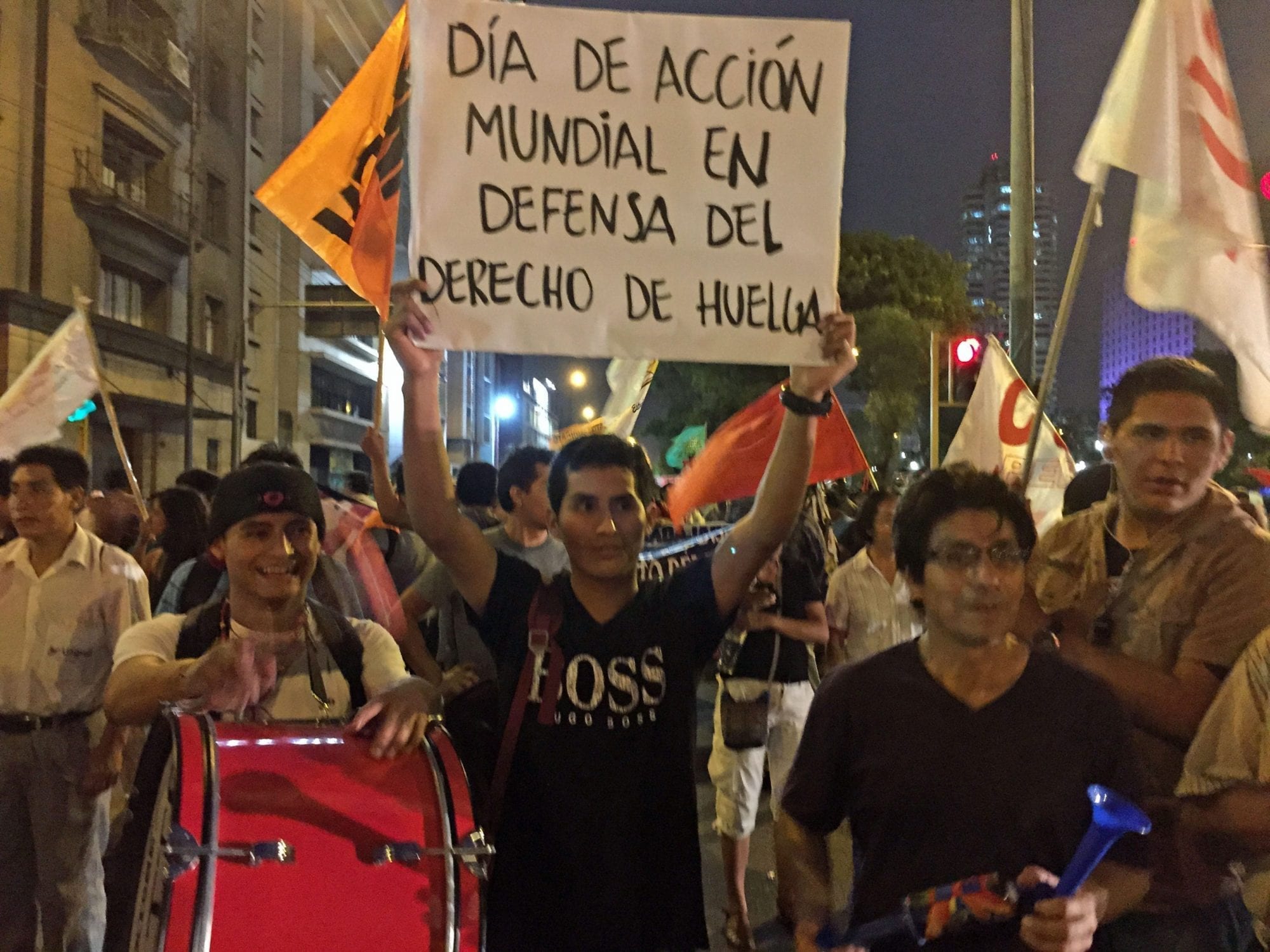

Thousands of workers marched in Lima on February 18, the global day of action for the right to strike. Credit: Solidarity Center

After lawmakers in Peru rammed through a law last November that reduced salaries and benefits for workers under age 25, they adjourned Congress and went to their home districts for the Christmas holiday, likely thinking the matter was over.

Tens of thousands of young workers thought otherwise.

“Students came together to organize protests, organize meetings with different sectors to fight the ‘reform,’” says Paola Aliaga, international relations secretary for the Autonomous Confederation of Peruvian Workers.

The unprecedented mobilization, in which up to 30,000 young workers and their allies marched in a series of protests, resulted in another unprecedented action: Lawmakers returned to session in January and immediately repealed the law.

“We hadn’t seen this turnout for many years. It was a win for all the sectors who were able to pull together,” according to Aliaga, speaking through an interpreter. Aliaga traveled to the United States last week and discussed the young workers’ campaign at the Solidarity Center in Washington, D.C.

Union members joined the protests, and workers of all ages understood that the creation of a two-tiered labor law system would be detrimental for everyone. The surge of activism by young workers is “new oxygen for the older folks in the movement,” says Aliaga.

Workers already are building on the momentum: On February 18, the global day of action for the right to strike day, thousands of workers and youth marched to Confiep, Peru’s chamber of commerce, to support the right to strike and call for a repeal of a mass layoff law and other recent anti-worker legislation.

Among those leading the protests last November were young worker activists from the textile and apparel, export-oriented agriculture and mining sectors—among the most vulnerable under the new law. They had plenty of support: A poll this year showed only one-fifth of Peruvians backed the law. Young workers protested at companies where employers supported the law, marched through Lima to Congress and woke up complacent lawmakers to the realities young workers face trying to make a living.

Peru President Ollanta Humala backed the bill and sought to confuse protesters about the date lawmakers would return to the capital, knowing they planned to rally when Congress opened the session, says Aliaga. Despite military presence at the protests and the detention of student activists, young workers remained steadfast in taking to the streets to peacefully voice their concerns.

“The role of the Solidarity Center in the garment sector has been key (to helping young workers understand their rights under Peruvian labor law),” says Aliaga. The Solidarity Center, with support from the U.S. Department of Labor, works closely with young Peruvian worker activists to help them analyze their labor rights; develop leadership, negotiating and organizing skills; and learn to advocate for their issues.