Jun 1, 2021

Half or more workers in key Cambodian industries were suspended for three or four months, and most were unable to support themselves on government aid during the pandemic, according to a new study that put hard data to the suffering of the country’s low-wage workers.

Some 53 percent of those working in tourism were suspended for an average 15 weeks, and 40 percent of workers in Cambodia’s garment and footwear industries were suspended for an average of 11 weeks, according to a survey of 1,525 workers by the Center for Policy Studies. Solidarity Center and The Asia Foundation supported the research, which reports results from July and August 2020. (See the full survey.)

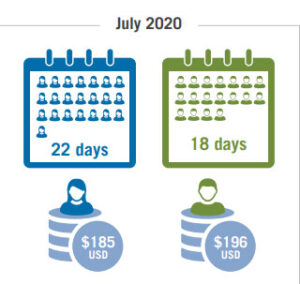

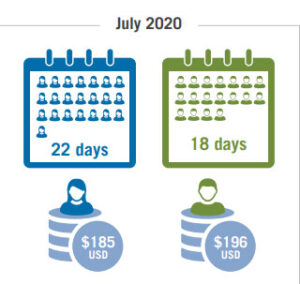

Women workers in Cambodia worked more and were still paid less than men during the pandemic. Source: CPS/Solidarity Center/Ponlok Chomnes

Women comprise the majority of workers surveyed and are the majority of 800,000 workers in the country’s garment and footwear industries. Before the pandemic, women were typically paid less than men. Yet, even when they returned to work in July 2020, they reported being paid less than men even though they worked more days than men.

All workers who returned to the job by July 2020 on average were employed for fewer hours and earned less than in July 2019.

COVID-19 an Excuse to Exploit Workers

Although many businesses were forced to temporarily suspend operations or shutter permanently during Cambodia’s first wave of COVID-19, some employers took advantage of the pandemic to lay off workers, union leaders say.

Further, hospitality and garment workers who returned to, or remained on the job, were not provided adequate personal protective equipment (PPE) or measures to ensure their safety, according to union leaders in Cambodia. Unions have been organizing to hold employers to account, negotiating for better protection measures.

Government Support Helpful, Not Sufficient

To assist garment and tourism workers during the country’s first wave of COVID-19, the Cambodian government launched several programs, including financial support for workers suspended from the job and a skills improvement training program. But workers interviewed for the survey said the suspension payments, which ranged $40 to $70 per month, were not sufficient to cover the roughly $69 they needed for basic monthly food expenditures.

Half of those surveyed say the suspension allowance was their only income, and more than 50 percent said they could not afford to send remittances to their family as a result of pandemic-related losses. Between 40 percent and 60 percent of workers surveyed say they took on debt to survive.

The government announced in July 2020 that businesses closed during COVID-19 were not required to pay workers hardship or layoff wages. Tourism sector operations also were not required to contribute the $30 per month toward the suspension payments. The government provided $40 per month.

Urgent Action Needed for New Pandemic Wave

Since February, Cambodia has experienced its worst COVID-19 outbreak, which has led to a deepening crisis for workers as many major cities and several provinces have been in strict lockdown.

During the pandemic, workers in many industries have been left out of public social protection programs, such as health coverage, and the survey recommends extension of these benefits for the most vulnerable.

The survey also recommends expanding skills improvement training programs and funding opportunities for temporary jobs.

Without such support, garment workers like Eang Malea are returning to their factories despite the risk of contracting COVID-19.

“I need to pay rent, utilities and debts, ” Malea, 26, said. “I worry that I will get infected by going to work without being vaccinated, but I don’t really have a choice.”

May 21, 2021

بالعربية

Agricultural workers in Jordan for the first time have fundamental protections on the job, including guarantees for safe and decent working conditions, following a two-year campaign by the Agricultural Workers Union in Jordan and its allies that resulted in passage of a historic regulation covering the agricultural sector.

“This is quite a landmark in Jordan. It’s the first time this type of legislation has passed,” says Hamada Abu Nijmeh, director of the Jordan-based Workers’ House for Studies. Under the regulation, any provision not mentioned falls under purview of national labor code.

The law applies to all workplaces that employ more than three agricultural workers, who now will receive 14 days annual paid leave and 14 days paid sick leave (or more, in cases of serious illness). Women are guaranteed 10 weeks paid maternity leave and there are now first-ever provisions for overtime pay. Significantly, the legislation also covers migrant agricultural workers, who frequently are not protected by countries’ labor laws.

COVID-19 Makes Visible Essential Workers

Agricultural workers in Jordan were key to developing the new labor regulation improving wages and working conditions.

Prior to passage of the regulation this month, there were no mandated safety inspections of farming facilities, leaving workers vulnerable to dangerous and unhealthy working conditions, such as exposure to poisonous pesticides. Agricultural workers, most of whom do not have formal labor contracts and are part of the country’s vast informal economy, were paid extremely low wages with no health insurance or other social protections. Working long hours, they were not guaranteed a day off during the week and not paid overtime. They were denied the freedom to form unions—the Agricultural Workers Union is not recognized by the government. Migrant workers still do not have the right to form unions under the new law.

Although a labor law covering agricultural workers was passed in 2008, the government never moved to put it in place, says Mithqal Zinati, union president. But as the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted essential workers like those who literally feed the world, the government became more receptive to the union’s campaign to ensure decent working conditions in the vineyards and fields.

“The agricultural sector is the food basket, the key source of stability that needs to be given priority to contribute to the stability of Jordanian state itself,” says Abu Nijmeh. “Part and parcel of that is to provide protection of workers. We told [the government] if you want to see this sector successful, you need to provide its protection.”

Abu Nijmeh and Zinati spoke with the Solidarity Center through interpreters.

Danger on the Job and Getting to Work

For Jordan’s 210,000 agricultural workers, more than half of whom are women, the day begins before dawn as they rush to meet the crowded trucks that transport them to the fields in the fertile Jordan Valley. Picking cucumbers, melons and okra in summer, citrus fruits in winter, the workers also weed fields, install water pipes and spray crops. They often are denied breaks, even as they work in the burning sun and harsh cold, and women have no access to toilets, leaving many with serious kidney issues and other illnesses, says Zinati. Just this week, a worker died of sun stroke in the fields, Zinati says.

Before they even arrive at the farms, women are subject to unsafe conditions on the packed vehicles they must use to get to work. Some 86 percent say they were involved in an accident on the commute, and 41percent say they are subjected to sexual harassment and other forms of gender-based violence during the journey, according to a study by SADAQA, a nonprofit organization championing the rights of women in Jordan. SADAQA produced the study, “Women Agricultural Workers in the Jordan Valley: Conditions of Work and Commuting Experiences and Challenges,” with Solidarity Center support.

Twenty or more workers are packed in a van licensed for five passengers, sitting on top of each other and in the luggage compartment, says Zinati. The vans take back roads to avoid police because they are not licensed, or licensed only to transport crops and other goods, and workers frequently suffer injuries as the overcrowded vehicles crash on the rough roads. Because most women work in shifts, they must commute two times per day, says Randa Naffa, SADAQA co-founder, speaking through a translator.

Together with the Solidarity Center, SADAQA produced a video on the outcome of the study documenting the hazards women face commuting to the fields. SADAQA, part of the Alliance to End Gender-Based Violence and Harassment in the World of Work, is using the video to campaign for regulations covering agricultural transport. The alliance is pushing the government to ratify International Labor Organization Convention 190 on ending gender-based violence and harassment at work. Convention 190 makes clear that employers and governments must take measures to ensure workers are safe on their work commute as well as in the physical workspace.

Worker Involvement Key to New Regulation

Agricultural workers were key to designing the new regulation. Beginning in 2019, leaders at the union and the Workers’ House met with workers on the farms to determine their needs and priorities. With worker input forming the basis of the draft regulation, campaign leaders applied labor regulations and human rights provisions from international standards and legislation from other countries to create a model regulation. The Workers’ House and the Solidarity Center then organized a meeting of agricultural workers to discuss the draft again and plan campaign steps, including social media outreach.

They formed a coalition with civil society organizations to launch an advocacy campaign that included petitions and public statements to the Ministry of Labor and other government officials which, along with social media outreach to mobilize public support, was key to moving the government to pass the regulation protecting these essential workers.

“I heard from the Ministry of Labor they said they were listening to, keeping abreast of what was spread in the media,” says Abu Nijmeh.

“The regulation that has just been promulgated, we hope it will protect female workers in this sector and it is the opportunity to create the political will to recognize the importance of women’s contributions to the agriculture sector and the importance of women’s contributions to other informal sectors,” says Naffa.

Worker Education Essential for Success

Abu Nijmeh, Zinati and Naffa all emphasized the need to ensure implementation and enforcement of the new regulation, especially workplace inspection, safety and health and child labor. Under the new regulation, children younger than age 16 cannot work in agriculture and those between ages 16 and 18 can only be engaged in non-hazardous work.

The regulation “shall never be enforced without pushing,” says Naffa. “We need to lobby more, engage in campaigns, reach out to the Labor Ministry, the Transport Ministry.” Key to its success is widespread education of agricultural workers about their rights, says Zinati.

A long-time union organizer who began by unionizing court workers in Beirut, Lebanon, Zinati says union committees are now set up in every village, and literacy classes and other education opportunities are offered so workers can better champion their rights.

“If I see people who are done an injustice, who are oppressed, the only way for them to gain their rights is for them to unite,” he says. “This legislation opens the horizon so workers can play a bigger role in pushing their rights,” he says.

May 20, 2021

While most consumers do not think twice when they select tomatoes, grapes or other readily available fresh produce in grocery stores, many of the agricultural workers around the world who spend their days harvesting vegetables, fruits and grains to fill the plates of others often cannot afford enough to eat.

“Sometimes I might have enough money to buy bread from one of the street vendors; sometimes I might not,” says Mabrouka Yahyaoui, 73, who works in Tunisia’s agricultural fields.

Yahyaoui is among nearly 1.5 million agricultural workers in Tunisia, more than 600,000 of them women, who suffer from high heat in summer and cold rains in winter for more than 10 hours a day, for which their daily wages are between $5.50 and $6. They are forced to give a chunk of their pay for daily transport to the fields in rickety vehicles where women say they are packed together unsafely, subject to sexual harassment, injury and even death. Hundreds of agricultural workers are killed in Tunisia each year as they travel to and from the fields.

“On board the vehicle, we are crammed in like sacks of potatoes, and, worse, the men would be riding along with us,” says Afef Fayachi, a Tunisian agricultural worker. “They would touch us, use swear words, and utter obscenities. Men harass women in every way. And all we can do is suck it up and keep quiet.”

But with the support of the Tunisian General Labor Union (UGTT), agricultural workers in Tunisia are standing up for their rights to safe transport, fair wages and decent work.

‘Invisible’ Essential Workers Demand Safe Work

Despite lack of protections against COVID-19, agricultural workers like Yasmina Yahyaoui risked their lives to support their families.

While the world became aware of “essential workers” during the COVID-19 pandemic, many remain out of the public’s eye, struggling to support themselves with few protections against contracting COVID-19.

“I can’t afford to buy a face mask for four dinars [$1.67] on a daily basis,” says Mayya Fayachi, who, like most agricultural workers, had to risk her health to support her family. As Yasmina Yahyaoui says, “How are we going to make a living if we stay at home?”

In Siliāna, an agricultural town in northern Tunisia, the Federation of Agriculture, a UGTT affiliate, is assisting workers in understanding their right to safe transportation and social protections like safety and health measures to protect against the deadly pandemic. Together with the Solidarity Center, the union worked with the women there to create a video in which they describe the unsafe and dangerous conditions they endure to get to work and home.

“The pains, the grief and privations of these wonderful, hardworking women can be channeled, transformed, into a fabulous resistance and an overwhelming will to overcome,” says Kalthoum Barkallah, Solidarity Center senior program manager for North Africa, who has led the Solidarity Center’s outreach among agricultural workers.

The Tunisian government is taking action in response to the union campaign to improve transportation for agricultural workers.

The video is part of the union’s campaign to build public support for improving the working conditions of agricultural workers and to urge the government ensure decent transportation—for instance, by providing small business loans to local entrepreneurs to operate vehicles that meet safety standards. The new International Labor Organization (ILO) regulation (Convention 190), which covers gender-based violence and harassment at work, makes clear that employers and governments must take measures to ensure workers are safe on their work commute as well as in the physical workspace.

Since the campaign launched, the Minister of Transportation has begun work on formalizing agricultural worker transport and called on governors to form a regional advisory commission to create a new category of license permits for the agricultural sector.

The government and unions also met in March for a first-ever regional symposium organized by the Ministry of Social Affairs on social dialogue and employment relations in the agricultural sector.

Wage, Equity and Respect

The campaign builds on surveys of, and discussions with agricultural workers in Jandouba, Kasserine, Manouba, Sidi Bouzid, Siliāna and Sousse about the conditions they face on the job, including sexual harassment and other forms of gender-based violence.

Workers also have helped formulate bargaining proposals around wages and working conditions, mechanisms for dispute resolution, promotion of workplaces free of violence and harassment, as well as mechanisms for ongoing social dialogue at workplace level.

At the national level, UGTT and its civil society partners are pushing for enforcement of workplace safety inspections laws, which employers are legally obliged to undertake.

Women agriculture workers also point to the need to address disparate treatment in wages and job opportunities between men and women. “The number of daily hours a woman worker is supposed to work must be clear, and how much she gets paid for that work must be clear as well,” says one agricultural worker.”

“Why are men getting paid at least 25 dinars ($9-$10) while I get paid 15 dinars ($5.50), of which I have yet to pay for transportation?” asks Aziza Guesmi.

The bottom line, says Fayachi, is about respect: “I ask for nothing but my rights.”

May 6, 2021

Garment workers and their union in Haiti are hailing a landmark settlement with a factory in Port-au-Prince that provided a total of $15,480 in back pay to 1,200 workers. The compensation covers 20 percent of the amount the employer deducted from workers’ paychecks for health care coverage by the government agency, OFATMA, but failed to pay to the agency. Haitian law requires employers to register workers in the system, deduct six percent of pay (split between employer and employee), and forward the contribution to OFATMA in a timely fashion.

The settlement follows the death of Liunel Pierre, a garment worker, who died in July 2020 after being denied life-sustaining dialysis treatment due to a lack of accrued health care funds.

After Pierre’s death, the Association of Textile Workers Unions for Re-importation (GOSTTRA) demanded the employer immediately remedy its failure to contribute to workers’ health insurance. After a weeks-long work stoppage, GOSTTRA members successfully brought management to the table. The settlement also covers many workers laid off during the pandemic and GOSTTRA is working with the employer to establish processes to contact the laid-off workers so they can receive the reimbursement.

Union advocates say this is the first time a Haitian garment sector union successfully negotiated a financial settlement agreement on behalf of workers and is holding the employer accountable without international or fashion brand intervention.

With Solidarity Center support, GOSTTRA printed fliers to publicize the settlement among workers that detailed the payment they should receive, accompanied by megaphone announcements at the factory. GOSTTRA is monitoring management’s action to ensure it correctly reimburses the workers.

Few factories in Haiti make the required contributions to the health or pension funds in accordance with the law, threatening the ability of workers to access health care. The International Labor Organization (ILO)’s Better Work Haiti (BWH) has reported continuous and widespread noncompliance for 10 years. In its most recent report, BWH found that 84 percent of employers did not comply with legal requirements for social benefits between October 2019 and September 2020.

In the same month as Pierre’s death, another garment worker, Sandra René, died from pregnancy complications after she also was turned away from the hospital where she sought medical care. As in Pierre’s case, the factory had deducted funds from her paycheck for health coverage, but failed to consistently pay into the system. Hundreds of garment workers marched with René’s casket in a funeral procession to OFATMA offices to protest her death.

Little Job Security for Garment Workers in COVID-19

GOSTTRA’s success comes as Haiti’s textile industry struggles to recover from diminished demand during the COVID-19 crisis. Workers still face layoffs and reduced working hours, with roughly a third of the 57,000 workers in the country’s garment industry suspended or terminated. Increasing violence in the country threatens workers’ ability to safely travel to work, further disrupting factory operations. Further, employers are clamping down on GOSTTRA union leaders who are trying to defend their members’ interests.

The victory also comes in an environment in which Haitians face increasing gang violence, kidnappings, and political polarization. Few elected officials remain, following the President Jovenel Moise’s dismissal of the lower Chamber of Deputies and mayors across the country. Thousands have marched to protest widespread assaults on the country’s democratic processes, and journalists and others taking part have been targeted by arrests and police violence. Last month, police fired tear gas into a church where Haitian bishops led a “Mass for the freedom of Haiti.”

May 5, 2021

The Solidarity Center is honored to announce that two dynamic leaders from within the U.S. labor movement have joined its Board of Trustees.

The new members are Gabrielle Carteris, president of the Screen Actors Guild-American Federation of Television and Radio Artists (SAG-AFTRA) and Alvina Yeh, Executive Director of the Asian Pacific American Labor Alliance (APALA). They will join current Board of Trustees members guiding the Solidarity Center as it strives to empower workers to raise their voice for dignity on the job, justice in their communities and greater equality in the global economy.

SAG-AFTRA President Gabrielle Carteris. Credit: SAG-AFTRA

Gabrielle Carteris became SAG-AFTRA president in 2016, after serving two terms as executive vice president. She became a household name playing Andrea Zuckerman on Beverly Hills, 90210 and recently starred in BH90210, a revival of the iconic show. Her extensive resume includes work in television, film and the stage, with recent credits including a recurring role on Code Black and guest-starring roles on Criminal Minds, Make It or Break It, The Event, Longmire and The Middle. As a producer, Carteris created Lifestories, a series of specials, and Gabrielle, a talk show that she also hosted. In her role as SAG-AFTRA president, Carteris chairs the National TV/Theatrical Contracts Negotiating Committee and leads the President’s Task Force on Education, Outreach and Engagement. She represents SAG-AFTRA with the International Federation of Actors (FIA), where she works to bring actors together across borders.

APALA Executive Director Alvina Yeh. Credit: APALA

APALA Executive Director Alvina Yeh. Credit: APALAAlvina Yeh serves as the Executive Director of the Asian Pacific American Labor Alliance (APALA) and Institute for Asian Pacific American Leadership & Advancement (IAPALA). Originally from Colorado, she comes from a Chinese family who fled from the war in Vietnam. Alvina, a lifelong community organizer with experience in electoral and issue-based campaigns, has a career committed to social justice. She is deeply passionate about building a movement where everyone has a fair shot in a thriving society, and brings an international lens on human and worker rights to the work of APALA. Yeh currently serves as the Co-Chair of the National Council of Asian Pacific Americans (NCAPA) and serves the Congressional Progressive Caucus Center Advisory Board and the National Korean American Service & Education Consortium Action Fund (NAKASEC AF) Board.

“I am thrilled that President Carteris and Executive Director Yeh are joining our Board,” said Richard L. Trumka, president of the AFL-CIO and chair of the Solidarity Center Board of Trustees. “They bring important and diverse points of view and a deep commitment to the Solidarity Center’s mission to support worker rights around the world, for everyone. We look forward to their contributions.”

Shawna Bader-Blau, executive director of the Solidarity Center said: “The Solidarity Center is dedicated to building cross-movement relationships and strengthening the connections between workers in the United States and workers around the world. So we are excited to begin work with these two labor leaders who bring a passionate interest in worker rights, additional connections to the U.S. labor movement and a wealth of experience in organizing, international solidarity and power building for workers in the United States and beyond.”

The Solidarity Center is the largest U.S.-based international worker rights organization helping workers attain safe and healthy workplaces, family-supporting wages, dignity on the job, widespread democracy and greater equity at work and in their community. Allied with the AFL-CIO, the Solidarity Center assists workers across the globe as, together, they fight discrimination, exploitation and the systems that entrench poverty—to achieve shared prosperity in the global economy.