Jul 18, 2019

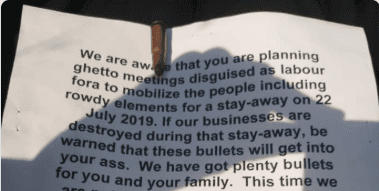

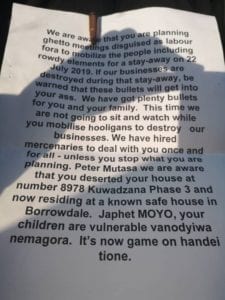

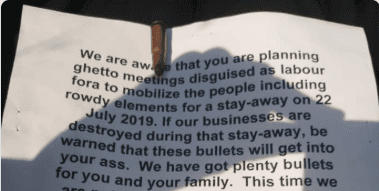

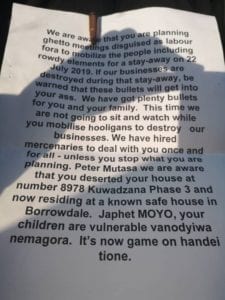

Bullets and an anonymous death threat were delivered to Zimbabwe Congress of Trade Unions (ZCTU) President Peter Mutasa and Secretary General Japhet Moyo yesterday in an apparent attempt to discourage a planned labor action later this month.

“This is the first time, for all we know in our history, that bullets are delivered at the homes of trade union leaders, said ZCTU in response.

Union leaders in Zimbabwe say this is the first time leaders have been threatened with death for seeking to exercise freedom of association. Credit: ZCTU

The identical threatening letters warn Mutasa and Moyo not to participate in an upcoming July 22 work stoppage by ZCTU members who, with other civil society groups, have been protesting rising prices in the country—including a 150 percent fuel price hike.

If Mutasa and Moyo “mobilize the people” the letter warns, the letter’s authors have hired mercenaries “to take care of you once and for all,” “have got plenty of bullets for you and your families” and know where Mutasa–currently in hiding for his own safety—is living.

“It’s now game on,” the letter ends.

ZCTU has faced numerous threats from authorities while Zimbabwe’s economy continues to flounder and inflation and price hikes further complicate Zimbabwean workers’ lives.

Mutasa has been forced into hiding by ongoing violence and intimidation by authorities. After ZCTU helped organize a national strike in January this year to protest price hikes, police seeking Mutasa allegedly assaulted his brother at his home. ZCTU staff also reported intimidation by police. Arrested and charged with subversion, Mutasa and Moyo have since remained in legal limbo as the Zimbabwe government repeatedly postpones their trials.

January’s violent clashes resulted in 12 deaths and 320 injuries, blamed by human rights organizations on the army and police.

In the aftermath of a similar protest in October last year, some trade unionists were beaten, Mutasa, Moyo and 33 other trade unionists were arrested, senior ZCTU leadership was forced into hiding and ZCTU Harare offices were cordoned off by some 150 policemen. The Zimbabwe Human Rights Commission found that torture of protesters by government forces before and immediately after the October national protest—consisting mostly of “indiscriminate and severe beatings”—was widespread.

An attempted fact-finding visit by a delegation of the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC) in February this year resulted in denial of visas for most of the delegation and the arrest of ITUC-Africa Secretary General Kwasi Adu Amankwah by state security.

The majority of Zimbabwean workers eke out a living in the informal economy, struggling to survive on less than $1 a day. Those with formal jobs often do not fare well either. A 2016 study by the Solidarity Center found that 80,000 workers in formal jobs did not receive wages or benefits on time, if at all. In many cases, they made only enough to get to work.

Jul 8, 2019

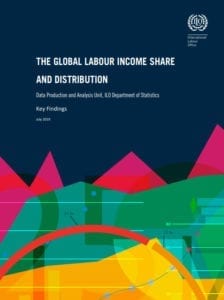

Some 650 million workers around the world earn less than 1 percent of global income—a figure that has barely changed in 13 years, according to a new International Labor Organization (ILO) report. At the national level, the share of income going to workers is actually falling, decreasing from 53.7 percent in 2004 to 51.4 percent in 2017.

“The average pay of the bottom half of the world’s workers is just $198 per month and the poorest 10 percent would need to work more than three centuries to earn the same as the richest 10 percent do in one year,” says Roger Gomis, an economist in the ILO Department of Statistics.

The report pushes back on the widely held view that overall income inequality is declining in the global south. Rather, increasing prosperity in China and India is skewing the data, which indicate pervasive income inequality in jobs around the world.

The report pushes back on the widely held view that overall income inequality is declining in the global south. Rather, increasing prosperity in China and India is skewing the data, which indicate pervasive income inequality in jobs around the world.

Overall, 10 percent of workers receive 48.9 percent of total global pay, while the lowest-paid 50 percent of workers receive just 6.4 percent, a new ILO dataset reveals, the ILO Labor Income Share and Distribution finds.

And the more top earners make, the less everyone else is paid, according to the report. But when income of middle- and lower-paid workers rises, everyone but the top earners gain.

The pay gap is especially large in struggling economies. In sub-Saharan Africa, the bottom 50 percent of workers earn only 3.3 percent of labor income, compared with the European Union, where the same group receives 22.9 percent of the total income.

“The majority of the global workforce endures strikingly low pay and for many having a job does not mean having enough to live on,” Gomis says.

Get Involved with Sustainable Development Campaign

The ILO data, requested by the ILO Global Commission on the Future of Work, will be used to monitor progress toward the United National Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs.) Representatives from around the world are set to meet this month for the High-Level Political Forum on some of the sustainable development goals, including SDG 8, which focuses on promoting sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full employment and decent work for all.

(The International Trade Union Confederation has launched a #Timefor8 campaign. Find out how you can take part.)

The ILO Labor Income Share and Distribution dataset includes 189 countries and provides the first internationally comparable figures of the share of GDP that goes to workers—rather than capital—through wages and earnings. It also looks at how labor income is distributed.

Jul 1, 2019

One union activist from the Workers’ Union of the Gildan Villanueva S.A. (SITRAGAVSA) was murdered and at least three others attacked during recent protests against the Honduran government’s efforts to privatize the country’s education and health systems, according to an independent human rights monitor, who will not be identified out of safety concerns.

The Platform for the Defense of Health and Public Education, a coalition of union and community organizations, led protests across the country in May and June. Security forces repeatedly responded by firing at protesters with live ammunition and tear gas.

Joshua Sánchez, 22, a union member, was shot in the head by police during protests in Villanueva after he sought refuge in a shop (see video), according to witnesses interviewed by the human rights monitor. Sanchez leaves behind a 4-year-old son.

Abel Martel received head wounds from assault by Honduran national police.

Among union leaders wounded, Nahún Rodríguez, president of SITRAGAVSA, was assaulted and threatened by a military policeman during protests in Villanueva, according to the human rights monitor. Abel Martel, SITRAGAVSA secretary general, was assaulted by national police and union delegate Skeyla Suyapa Gomez received a face wound from a tear gas bomb dropped by the national police. The union leaders, workers at apparel factories, joined thousands of teachers and health care workers in solidarity with their struggle and to demonstrate the importance of maintaining quality public services for all Hondurans.

Spending on education and culture has dropped from 33 percent of the national budget to 20 percent over the past decade, with wages and infrastructure spending frozen. Some 40 percent of emergency rooms have inadequate medical coverage, according to the Honduras National Commission for Human Rights. Educators and health care workers say privatizing health and education systems will further decrease services and lead to layoffs.

Few Perpetrators Brought to Justice Despite Global Condemnation

The Network Against Anti-Union Violence in Honduras, which each year issues a report documenting violence against and murders of Honduran union leaders and members, is among local and international organizations denouncing the deadly crackdown. Yet despite widespread global condemnation, union leaders and members continue to be targeted, and few, if any, perpetrators are brought to justice.

The International Labor Organization this month issued its second complaint against the Honduran government in as many years over the continuing attacks on union activists, indicating its serious concern regarding “the allegations of acts of anti-union violence, including the allegations of physical aggression and murders, and the prevalent climate of impunity.”

In 2012, the AFL-CIO and 26 Honduran unions and civil society organizations filed a complaint under the labor chapter of Central American Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA). The complaint, filed with the U.S. Department of Labor’s Office of Trade and Labor Affairs, alleges the Honduran government failed to enforce worker rights under its labor laws. In a February 2015 report, the U.S. Trade and Labor Affairs office said Honduras had made virtually no progress since 2012.

Jun 27, 2019

Mexico’s stubbornly low wages and its complex industrial-relations system that denies workers their right to freedom of association and robs them of the ability to demand better wages and working conditions were front and center at a House Ways and Means subcommittee hearing on Mexican labor reform yesterday in Washington, D.C. A representative of the Solidarity Center and other rights and trade experts testified.

Gladys Cisneros, Solidarity Center country program director in Mexico, told members of the subcommittee on trade that Mexico’s new labor law is a good first step, but implementation will be a challenge and strong monitoring of worker rights are essential for it to succeed. Mexico passed labor law reform in April to improve workers’ ability to freely form unions of their choice and have more control over collective bargaining contracts.

Mexico has a long history of suppressing worker rights. Workers face daunting obstacles when challenging the “protection union” system, in which secret employer “protection contracts,” negotiated between a non-democratic union and a complicit employer without the knowledge of the workers, are widespread. Independent unions rarely succeed in defeating protection unions that have historical presence, political ties and financial capacity to exert influence over workers.

In her written testimony, Cisneros estimates that “only 1 percent to 2 percent of Mexican workers are members of an independent trade union, and just 1 percent of Mexico’s workers are covered by authentic collective bargaining agreements that were reviewed and ratified by workers.

“When workers decide to organize a new independent union, it is not uncommon for an employer to announce that the workplace is already covered by an agreement and that the workers already have a (protection) union. If no protection union is in place, employers can quickly find one to sign a contract and thwart the independent organizing effort,” Cisneros said in the written testimony.

She said that ousting protection unions is extremely difficult and that shifts both cultural and in approach are required to implement labor reforms. The new labor law already is being challenged by deeply entrenched protection unions and employers, Cisneros said.

Workers Key to Mexico’s Labor Law Success

Cisneros stressed the role of workers in implementing the labor law reform.

“For the reform to succeed, workers must be placed at the center of implementation. They must be sufficiently knowledgeable and empowered and given concrete guarantees that their attempts to exercise these newly enshrined rights will not be met by the usual responses from employers and government. Only when workers, through their efforts in the workplace, can exercise and invoke these new laws will the legal changes be made real and reach their potential to improve working conditions and wages,” she said.

Cisneros described cases in which workers freedom of association was violated and said that while the new labor law is designed to first weed out sham contracts and ghost unions, they then must be replaced with authentic unions led by workers. Mexico’s independent labor movement is already stretching its limited financial resources, political capital and capacity for mere survival.

Cisneros also recommended that workers must be positioned to imagine new possibilities and develop new expectations if they are to invoke the new legal framework and serve as the agents to apply these changes.

The reform speaks to the persistent, dire lack of democracy in labor relations and the inability of workers, in most cases, to freely choose their representation and effectively negotiate their terms of employment, she said.

Also testifying were AFL-CIO International Department Director Cathy Feingold, University of California Berkeley Center for Latin American Studies Professor Harley Shaiken and Instituto Tecnológico Autónomo de México assistant professor Joyce Sadka.

Jun 25, 2019

Belarus, Burundi, Mauritania, Russia, Saudi Arabia, South Sudan and Turkmenistan are among the 22 countries with the worst human trafficking records in 2018, according to the U.S. State Department’s annual Trafficking in Persons Report.

The report notes that for the first time, a majority of victims in 2018 were trafficked within their countries of citizenship, especially in cases of labor trafficking.

In Turkmenistan, where the government “continued to engage in large-scale mobilizations of its adult citizens for forced labor in the annual cotton harvest and in public works projects, no officials were held accountable for their role or direct complicity in trafficking crimes,” according to the report.

Further, the report states that “the continued imprisonment and abuse of an independent observer of the cotton harvest and state surveillance practices dissuaded monitoring of the harvest during the reporting period.”

Gaspar Matalaev, a labor rights activist with Turkmen.news, who monitored and reported on the systematic use of forced adult labor and child labor in Turkmenistan, remains falsely imprisoned since 2016, days after Turkmen.news published his extensive report on the country’s forced labor practices.

He has been tortured with electric shocks and held incommunicado, according to the Cotton Campaign, a coalition of organizations, including the Solidarity Center, working to end forced labor in the cotton fields. (Send a message to the Turkmenistan government to immediately release Matalaev.)

Uzbekistan, another country with vast, state-sponsored forced labor in the cotton fields, remained on the watch list, a ranking indicating more progress by the government than in Turkmenistan. Although the Uzbekistan government has made strides in ending forced labor, public-sector employees continue to be coerced into a variety of construction and municipal service work, as documented in a recent report by the Solidarity Center and the Uzbek-German Forum for Human Rights (UGF). In addition, at least 175,000 people were forced to harvest cotton in Uzbekistan’s 2018 harvest.

Migrant Workers Vulnerable to Exploitation, Trafficking

The Trafficking in Persons report also details how labor recruiters often act as human traffickers, taking advantage of migrant workers who lack information on the hiring process, are unfamiliar with legal protections and options for recourse, and often face language barriers.

“Certain unscrupulous recruitment practices known to facilitate human trafficking include worker-paid recruitment fees, misrepresentation of contract terms, contract switching, and destruction or confiscation of identity documents,” the report states.

The report continues: “Low-wage migrant laborers are extremely vulnerable to and at high risk of exploitative practices such as unsafe working conditions, unfair hiring practices, and debt bondage—a form of human trafficking.”

Each year, the State Department ranks countries in one of four tiers, basing its assessment primarily on the extent of governments’ efforts to meet the minimum standards for the elimination of human trafficking outlined in the U.S. Trafficking Victims Protection Act (TVPA). Countries at the bottom, Tier 3, fail to show they are making any effort to end human trafficking.

The State Department has issued the report annually since 2001, following passage in Congress of the TVPA in 2000.