Sep 21, 2018

Of the 152 million children forced to work around the world, nearly half—73 million—are engaged in hazardous work, which includes dangerous, unsafe working conditions, and work that exposes children to physical, psychological or sexual abuse, according to the U.S. Department of Labor 2017 Findings of the Worst Forms of Child Labor report released yesterday. In 2015, 168 million children labored worldwide.

Most child labor—some 70 percent—occurs in agricultural

sectors, but it takes place in all industries. While the global trend in child

labor is downward, in sub-Saharan Africa the proportion of children in child

labor is actually rising—with one in five children engaged in child labor,

according to the report. Some 48 percent of child laborers were younger than

age 12.

The report also assesses countries’ progress in reducing child labor and found that three countries—Burma, Eritrea and South Sudan—received a “no advancement” assessment due to their government’s direct or active involvement in forced child labor. In total, 12 countries were assessed as making no advancement.

After years of receiving an assessment of “no advancement” for the forced mobilization of children in the cotton harvest, Uzbekistan received a “moderate advancement” for progress in reducing child labor. But the U.S. Department of Labor continues to call for an end to the mobilization of adult forced labor in cotton harvests. The Dominican Republic also received an assessment of “moderate advancement” because, in contrast to previous years in which it received an automatic “minimal advancement,” no cases were reported of children withoutidentity documents being denied access to education, an unlawful practice that mainly targeted children of Haitian descent.

Eswatini (formerly known as Swaziland), moved from “no advancement” to “minimal advancement” because there was no evidence in 2017 that local chiefs were forcing children to perform agricultural work or other tasks through kuhlehla, a customary practice that requires residents to carry out communal work, including in chiefs’ houses or fields.

The report highlighted work by the Global March on Child Labor, which organized a virtual march in May and June 2018 to commemorate its 20th anniversary and spread awareness about hazardous child labor and the safety and health of young workers. The Global March, a Solidarity Center partner, is headed by Kailash Satyarthi, who won a Nobel Prize in 2014 for his lifetime commitment to the cause of eradicating child labor. Solidarity Center Asia Regional Director Tim Ryan chairs the Global March board of directors.

The Labor Department also released its annual List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor, which documents more than 140 goods produced by child labor or forced labor in violation of international standards. Ten new goods were added to the 2018 list, including amber, cabbage, carrots, cereal grains, lettuce and sweet potatoes.

The “Worst Forms of Child Labor” report is required under

the 2000 Trade and Development Act (TDA), and the List of Goods Produced by

Child Labor or Forced Labor was first published in 2008, as mandated by the

Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act. Both acts aim to promote

global economic growth and build strong international trade partnerships that

hinge upon the reduction of child labor, forced labor and human trafficking.

Sep 10, 2018

For the first time in years, large numbers of public-sector employees were not forced to carry out spring fieldwork in Uzbekistan’s cotton fields, although instances of child labor and forced labor were documented, according to a new report by the Uzbek-German Forum (UGF).

Despite progress, “No Need for Forced Labor when Farmers are Empowered to Pay Decent Wages: Spring Cotton Fieldwork 2018” finds that the government-run system of forced cotton production remains in place.

“The shift from the mobilization of workers in education and healthcare institutions to mostly voluntary labor to prepare fields this spring is significant and should be commended,” said Umida Niyazova, UGF executive director. “It is clear that structural problems remain, however.”

“Further scrutiny and careful monitoring will be required during the 2018 harvest to see how far those changes have actually gone in ending forced labor in Uzbek cotton production, and what still remains to be done,” Niyazova continued.

New Policies Enable Farmers to Hire Voluntary Workers for Spring

Human rights activist Fakhriddin Tillayev (right) was among political prisoners Uzbekistan released this year. Credit: Solidarity Center

This spring, seven monitors for the Uzbek-German Forum conducted site visits to farms, schools, colleges, clinics, hospitals, banks, markets and local government agencies and interviewed dozens of farmers, education and medical workers, children, union leaders and local government officials.

The monitors found no large-scale organization of forced labor as occurred in past spring weeding seasons. Those who still reported being forced to work included the guards, cleaners, librarians and specialists at schools in the Bayavut district, who said that they weeded cotton fields for 15 to 20 days in May and June.

The report cites two factors behind the reduction in forced labor this spring, including higher procurement prices set by the government. Farmers are required to sell their crop to the government for a set price, and the government this year raised the price from $370 to $706 per metric ton. And for the first time, farmers were allowed to receive cash from banks. With more access to cash and higher payments, farmers are less reliant on unpaid labor for the springtime work required to produce cotton quotas set by the government.

Despite these improvements, farmers also described an overall lack of autonomy and intrusive, punitive oversight by local authorities who impose crop quotas. Penalties for missing those quotas can be severe, including physical violence and loss of one’s land, and state agents apply enormous pressure for them to be met. One farmer said to monitors: “The public prosecutor screams, ‘Quickly plant cotton.’ He threatens, he says, ‘or else I’ll have a criminal case against you.’”

In recent months, the government of Uzbekistan has been willing to talk about reducing forced labor and began releasing political prisoners, including worker rights activists.

“We are seeing unprecedented change in Uzbekistan right now, after a decade of international pressure. We hope respect for workers’ rights, especially ensuring fundamental rights for workers to organize together and negotiate for better working conditions, will follow,” said Solidarity Center’s Eastern Europe/Central Asia Director, Rudy Porter.

The Cotton Campaign, of which Solidarity Center is a member, developed a roadmap for the government of Uzbekistan to dismantle the forced labor system of cotton production, which was presented to government officials during high-level meetings in Tashkent in May 2018.

Sep 6, 2018

A new Solidarity Center report, “Working for Peace in North-East Nigeria: A Challenge for Nigerian Trade Unions,” outlines the devastating toll of Boko Haram violence on people living in northeast Nigeria, in particular on civil servants and their families, and how the labor movement will be essential to responding to the aftermath of the crisis and rebuilding for sustainable development and peace.

The report, with accompanying worker testimonials, was launched Tuesday at a 50-person event in Abuja, Nigeria’s capital. featuring three workers victimized by Boko Haram; Solidarity Center, Borno-based trade union partners; representatives of Nigeria’s National Labor Congress (NLC)—including President Ayuba Wabba; Public Services International (PSI); the Trade Union Congress (TUC); the Organization of Trade Unions of West Africa (OTUWA), as well as the press.

“We have lost more than two thousand workers—teachers, local government workers, health workers,” said Wabba, who pointed to lack of good governance as the root cause of conflict.

“We must work assiduously to try to address issues of human and trade union rights,” he continued.

Three years of sustained work by NLC-affiliated public-sector unions in the region preceded the report’s publication. The unions that represent teachers and hospital workers, among groups specifically targeted by Boko Haram militants, were able to document and begin to address the economic and psycho-social impacts of violence on their members and the community at large. “As integral members of their communities,” the report states, “union members are well-positioned to assess the local situation, understand the needs of community members and communicate this essential information to better facilitate the post-conflict rebuilding process.”

Report recommendations include that the government of Nigeria follow principles established by ILO Recommendation 205 to work in coalition with trade unions and employers in creating long-term solutions for a sustainable and inclusive economy, including bringing back family-sustaining jobs and helping institutions such as schools and hospitals recover and rebuild.

Aug 23, 2018

Two female migrant workers from Myanmar were arrested in Thailand, fined and await deportation for volunteering their time to teach children of migrant workers at a Buddhist monastery, an action the Thailand-based Human Rights and Development Foundation (HRDF) is calling “illegitimate and unjustified.”

The two women, who hold valid passports, visas and work permits, volunteered at the Laem Nok Monastery in southern Thailand in addition to the jobs for which they were hired. But immigration officials charged them with performing work without a permit to teach, even though the time they spend instructing the children is unpaid, according to HRDF and the Migrant Working Group (MWG). The MWG is a network of non-governmental organizations working on health, education and migrant workers’ rights that includes the Solidarity Center.

The arrests occurred despite the statement of one worker’s employer who told police the worker is lawfully employed and has been excused to take leave from her regular job painting boats because she is pregnant. The monastery also affirmed the two workers taught without pay, actions that are not illegal in Thailand, says HRDF, a Solidarity Center partner.

The women were forced to sign a document in Thai that they did not understand, in which they admitted they committed a crime, and received a fine of 5,000 Baht ($153) in lieu of imprisonment. They will be banned from re-entering to work in Thailand for two years, according to HRDF. A Myanmar national holding a tourist visa who observed the volunteers teaching was also arrested on the same charge.

“The arrests could signal a strong discouragement to other similar teaching programs in the country and could also pose a negative impact on education opportunities for migrant children as a whole,” HRDF and MWG said in a statement.

Volunteers Taught Children at Risk of Exploitation

The Laem Nok Monastery has operated a learning center for children of migrant workers for more than four years. The program began after the community recognized that migrant children, who are often left without care when their parents are working can be targets of forced labor, human trafficking and other forms of exploitation. With support from community fundraising, the monastery dedicated a learning space where children are taught the languages and cultures of Thailand as well as those of their origin countries. Local businesses provide funding for food and teaching supplies, but the teachers are unpaid volunteers, including local college students.

HRDF and MWG are calling on Thailand’s Department of Employment, Ministry of Labor to establish clear guidelines for enforcing compliance with work permits and to review the policy that restricts migrant workers from becoming paid or unpaid volunteers.

The groups also are urging police to ensure migrant workers’ legal rights are respected, including the right to legal counsel and to bail during pre-trial.

“The arrests have created undeserving traumas to the children in the classroom who had to witness their teachers being arrested and taken away in front of them,” says HRDF.

Aug 20, 2018

From the ancient temple complex of Angkor Wat to the palaces and pagodas of Phnom Penh, Cambodia draws vast numbers of tourists from around the world—more than 5.6 million in 2017—who help make the country the sixth fastest-growing economy in the world, with travel and tourism contributing 14 percent of total GDP in 2017.

But even as tourist visits accelerate and the economy booms, the hotel receptionists, room cleaners and maintenance staff essential to this economic growth are struggling to get their fair share of economic prosperity.

At the five-star Sofitel in Phnom Penh, where a room can cost up to $800 a night, base wages are $70 a month plus a percentage of the guest service charge, for a monthly salary of roughly $200 a month. Yet a basic living wage in Cambodia for one person is between $156 a month and $259 a month, and most workers have families to support.

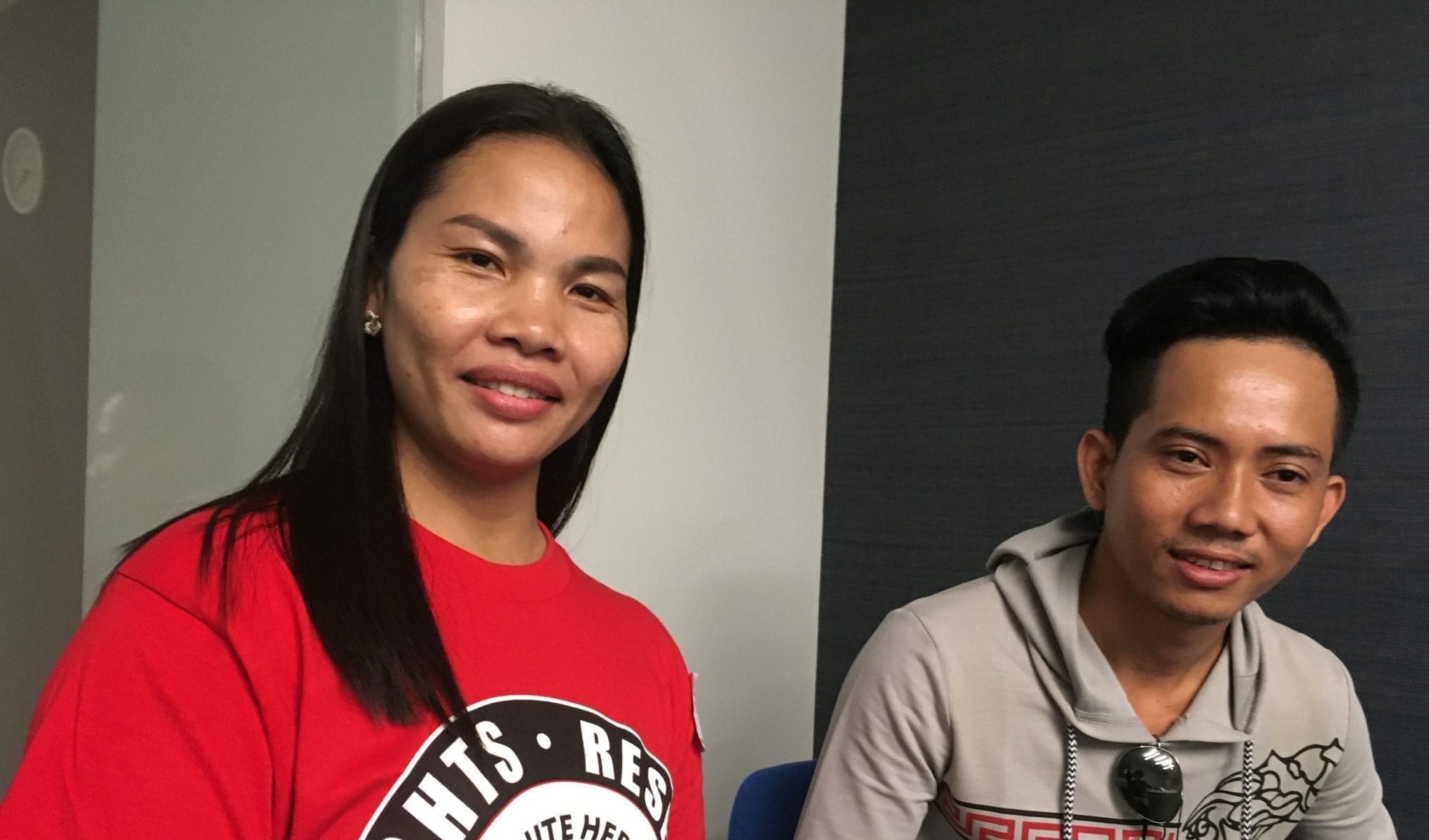

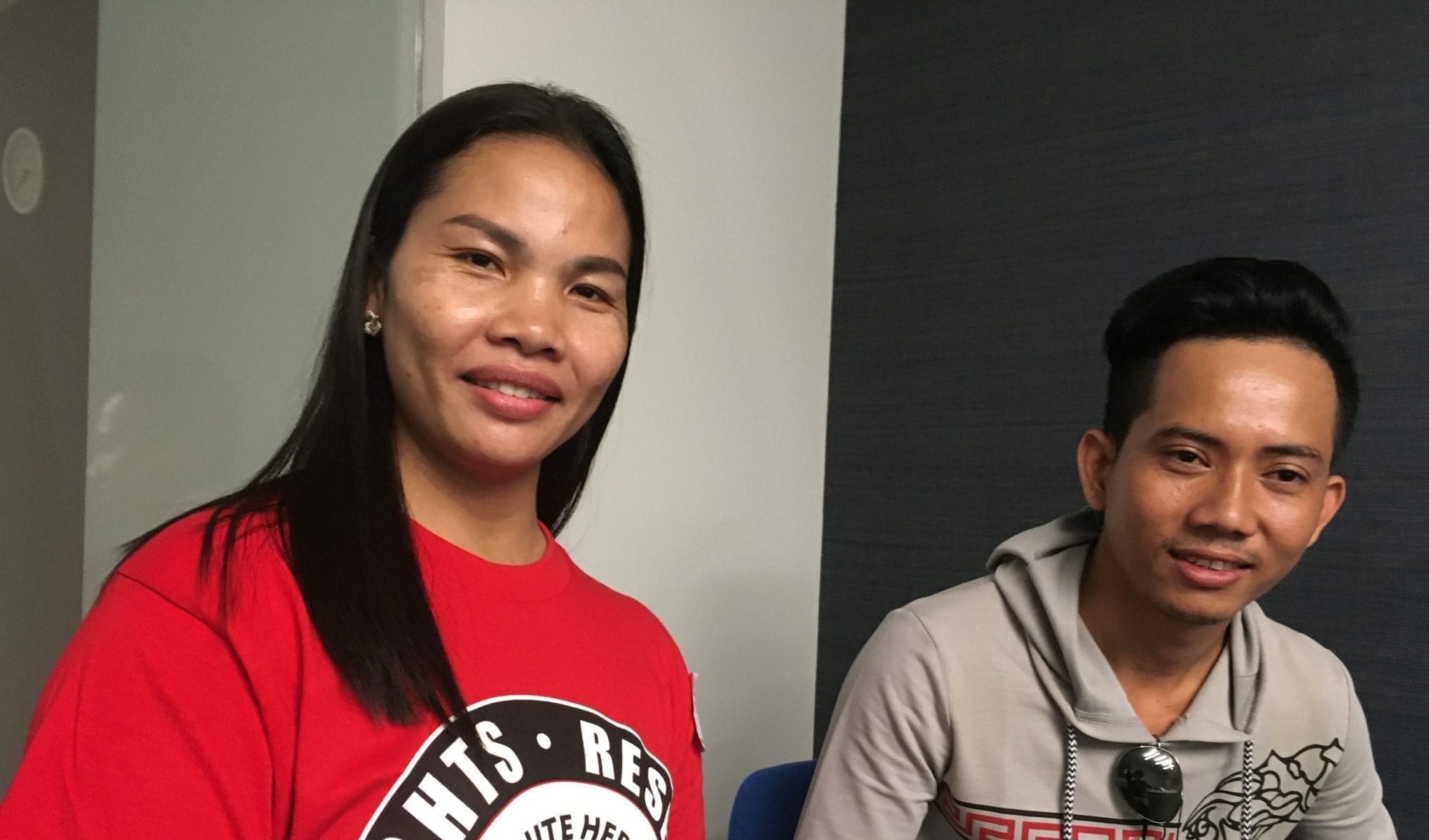

“I want the employer to give a better base wage for employees,” says Phat Saroun, president of a newly formed union at the hotel. “I want to increase the base wage to $85 a month,” he says, speaking through a translator. Phat’s union is part of the Sofitel Phnom Penh Phokeetra Hotel Independent Solidarity Union (SPPHISU).

Phat and five other Cambodian hotel workers traveled to Washington, D.C., in recent days as part of a Solidarity Center delegation to meet and strategize with hotel union activists and other leaders in the U.S. union movement.

A Union Makes a Big Difference

Tourists to Angkor Wat can pay high prices for hotels, even as workers barely earn a living wage. Credit: Wikipedia

With no legal minimum wage in Cambodia’s service sector, the nearly 1.2 million jobs in travel and tourism offer low pay and precarious employment—unless workers succeed in forming a union.

“There are two Sofitels in Cambodia and at the one in Siem Reap, they have a collective bargaining agreement. At my hotel in Phnom Penh, working conditions are very different,” says Phat, who is working to achieve a single contract with both hotels.

In Siem Reap, where nearby Angkor Wat is Cambodia’s biggest tourist draw, Mao Vanda has been part of her 235-member hotel union since its formation 12 years ago. Now a union secretary and shop steward, Mao describes the many improvements workers have negotiated at the luxury Raffles Grand Hotel.

“Working conditions are better than before,” she says, speaking through a translator. “Monthly salaries now average between $160 and $170 in the off-peak season, and around $350 during the five busiest tourist months.

“For instance, before we had a collective bargaining agreement, women were paid only 50 percent of their base salary during the [legally mandated] 90-day maternity leave. After the collective bargaining agreement, women are paid their full salary and full guest service charge for 100 days after giving birth. If they require a surgeon, the employer gives them $500.”

Workers Fear Losing Their Jobs if They Form a Union

Yet despite the significant improvements in wages, benefits and working conditions for unionized hotel workers, challenges to forming unions means union only represent between 4,000 hotel workers and 5,000, says Nimol Vorng, Solidarity Center program officer in Cambodia.

Hotels frequently hire workers on five-to-six month contracts and as a result, “Workers are afraid to join a union because after the contract is finished, the employer won’t hire you any more,” he says.

Although workers in the travel and tourism sector account for 13.6 percent of total employment, “unions don’t have strong voice or the power to negotiate with employer,” he says.

Yet Phat, Mao and other workplace-level union leaders who met with U.S. union activists are striving to strengthen their unions at the workplace and throughout the country’s hotel industry, and they plan to take back to their unions the lessons and experiences they gleaned in the United States.

For Mao, that means planning big. “For every hotel, we want to have a standard [national] minimum wage,” she says.

Solidarity Center Exchange Programs are funded by a grant from the U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs.