Mar 28, 2018

After years of hardship for workers due to illegal corporate employment practices and a lack of recognition of their rights, a Colombian union of subcontracted palm workers won direct employment contracts for 730 of its members. Successful negotiations followed a 20-day strike earlier this year that brought management of the largest palm oil producer in the country, Indupalma, to the table.

Jorge Castillo, UGTTA president, conducts the ratification vote for the accord. Credit: Digna Palma

Last year, the palm oil workers formed the General Union of Third-Party Agribusiness Workers (UGTTA). Despite the region’s history of threats and violence against workers who form unions, the UGTTA has grown from 248 to some 1,010 members. The union reports four members received death threats in 2018.

The Ministry of Labor determined in 2016 that Indupalma illegally subcontracted the majority of its 1,200-person workforce. The company imposed a model of phony cooperatives, essentially classifying workers as owners without labor rights or decent working conditions. As subcontracted workers, the palm oil workers had no rights under Colombia’s labor laws, including the minimum wage, freedom of association and the right to negotiate working conditions. They walked off the job outside San Alberto January 25 to demand formal work status.

Beginning in 2017, a broad coalition of palm workers’ unions known as the Worker Pact (Pacto Obrero) provided critical organizing and advocacy support, which, in addition to a sound legal strategy and international pressure, prompted the Ministry of Labor to intervene and facilitate a negotiation that led to a formalization accord between UGTTA and Indupalma.

The accord finalized on March 15 calls for the creation of two new affiliate companies (with sufficient capital and investment to meet legal obligations to the workforce) that will directly employ workers from two Indupalma work sites in the Magdalena Medio region. The accord also explicitly abolishes the use of the cooperative model. This process is to be completed by August 2018.

The union unanimously ratified the accord and has expressed deep gratitude for the solidarity it has received. The 730 members who will become direct employees will enjoy the full protection of the labor law and will be entitled to the minimum wage, social security benefits, health and safety standards, and organizing and collective bargaining rights. This win has lifted the entire San Alberto community, as families anticipate that improved wages and job security will provide additional resources that benefit their households and help educate their children.

The Solidarity Center will continue to work alongside the UGTTA and Pacto Obrero to monitor enforcement of the accord.

Mar 27, 2018

Georgia’s new workplace safety and health law is a step forward but does not include sufficient enforcement mechanisms and only covers workers in a few industries, according to the Georgia Trade Union Confederation (GTUC).

“What Georgia’s workers desperately need are laws to force employers to take their safety seriously, and hold them criminally responsible when they do not,” says GTUC Vice President Raisa Liparteliani. For the current labor laws to have any effect, “we first need an inspection department with the clout to back them up,” she says.

Some 455 workers died and 793 were injured on the job between 2007 and 2017, according to the GTUC, using data from the Georgia Ministry of Internal Affairs. Already this year, 12 workers have died. These figures do not include workers who have died or were injured because of occupational illnesses like black lung disease, a common and often fatal workplace hazard for miners, or other on-the-job injuries that manifest after the immediate incident. Also, according to the GTUC, some industrial accidents are not reported in part because employers threaten or blackmail workers into remaining silent.

The law, in effect March 21, covers only workers in high risk, hazardous and dangerous work, and stipulates that workplaces may be inspected only at the invitation of the owner, who must be given at least five days notice.

“The law does not provide regulations that create an efficient, fully fledged labor inspection system in compliance with the International Labor Organization (ILO) convention on labor inspection (Convention 81), in which inspectors have unlimited, free access to all public and private workplaces without the permission of employers or other officials,” according to the GTUC.

Restoring Labor Rights

Under a previous government, Georgia’s labor laws in 2006 were replaced with a labor code focused on the rights of employers. A new government in 2015 created a labor inspection department in line to meet the requirements of an Association Agreement with the European Union. Yet since then, says Liparteliani, the number of people dying and being injured in the workplace has instead increased.

A major shortcoming of the new labor inspection department is that it says “nothing of other areas of labor rights,” she says.

“Labor rights are inseparable from safety issues; a vast majority of workplace accidents occur due to physical fatigue, which is understandable when workers can’t take holidays, can’t take days off when they’re ill, and are forced to work extra hours.”

As it works to establish a labor inspection system in compliance with ILO standards, the GTUC plans to bring the issue to the Tripartite Social Partnership Commission that oversees the European Union-Georgia Association Agreement.

Mar 23, 2018

Two union activists were murdered in Guatemala and one in Honduras, while dozens of others were targets of violence—including threats of murder, kidnapping and stalking—over the past year, according to two reports released this week.

In Guatemala, “where the unionization rate is less than 1 percent, intolerance and violence against workers highlights, precisely, the mechanisms of terror to limit and, in many cases, to ignore those rights on the part of employers,” according to the Annual Report on Anti-Union Violence. The report, by the Network of Labor Rights Defenders of Guatemala (REDLG), found two more instances of violence in this reporting year (February 2017–February 2018) than in the previous period.

Since 2004, 87 union leaders and activists have been killed in Guatemala, one of the most dangerous nations in the world for union rights activists.

In Honduras, many of those targeted in the 39 documented instances of violence were organizing unions or seeking collective bargaining agreements in the agro-industrial palm oil sector in Colón, according to the report, “Freedom of Association and Democracy” by the Anti-Union Violence Network. Both networks are Solidarity Center partners. (The report is available in English, including an Executive Summary, and Spanish.)

Honduran Union Activist Targeted after Report Released

Isela Juárez is among Honduran union activists targeted with death threats. Credit: Anti-Union Violence Network of Honduras

Two days after the report on Honduras was released this week, union leader Isela Juárez, who has received death threats for her worker rights activism, was followed in a high-speed chase by two men on motorcycles before she took refuge inside the San Pedro Sula City Hall. Juárez, president of the Union of Workers of Municipal, Common and Related Services, (SITRASEMCA), also had been honored for her defense of human rights over the weekend.

The report on Honduras finds that 51 percent of the alleged perpetrators are public officials, including the military police, along with municipal authorities who harassed, coerced and fired nine workers to prevent them from forming unions.

Some 100 unionists and other members of civil society took part in the report’s launch, and several people violently targeted for their activism described their experiences. Since the network in Honduras began documenting cases of anti-union violence in 2015, 69 union activists have been targeted with violence, including seven who were murdered.

The report on Honduras also highlights a correlation between increased violence and the growing role of women in union leadership, and documents cases of unionists attacked during the post-election violence as they sought democracy.

In both countries, poverty and extreme poverty is high, with the World Bank estimating that in 2016, 65 of every 100 Hondurans lived in poverty, and 43 of every 100 in extreme poverty. In Guatemala, despite a growing economy, poverty rose to 59.3 percent in 2014.

The U.S. government has declined to consider anti-union violence in Central American Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA) complaints filed by the AFL-CIO and Guatemala and Honduran trade unions.

Mar 16, 2018

Women farm laborers are among the most exploited workers around the world—forced to endure long days in harsh conditions, paid subsistence wages and often subject to physical and psychological violence on the job. Yet they are standing up for their rights and demanding workplace justice through their unions and worker associations, as two Solidarity Center panels highlighted yesterday in New York City.

Hind Cherrouk says women farm workers in Morocco were key to winning a bargaining agreement that addressed gender inequality. Credit: Solidarity Center/Tula Connell

“The inability to access proper union representation and collective bargaining rights undermines women’s opportunity to advance themselves,” says Hind Cherrouk, Solidarity Center country program director for the Maghreb Region. Through empowerment and leadership training with the Democratic Labor Confederation (CDT) and Solidarity Center, Cherrouk says women farm workers in Morocco overcame social and cultural norms that repressed them and “actually sat at the negotiating table across from employers” and negotiated the region’s first-ever collective bargaining agreement covering farm workers.

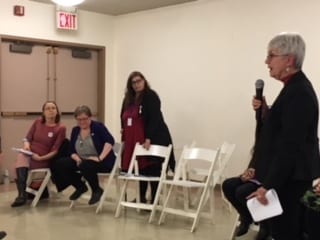

Cherrouk joined workers and Solidarity Center representatives from Jordan and Peru on the Solidarity Center panel, “Rural Agricultural Women Workers Organizing to Increase Equality and Empowerment.” The panel, moderated by Robin Runge, Solidarity Center senior gender specialist, is among dozens of parallel events taking place this week in conjunction with the 62nd session of the United Nations Commission on the Status of Women (CSW). The CSW this year is emphasizing the challenges and opportunities in achieving gender equality and the empowerment of rural women and girls.

Women farm workers in Peru are negotiating contracts that enable them to care for their families. Samantha Tate Credit: Solidarity Center/Tula Connell

In Peru, women farm workers who participated in Solidarity Center gender equality and leadership training have gone on to negotiate child care at the workplace and enforcement of laws like paid time for breastfeeding and guaranteed jobs following maternity leave, says Samantha Tate, who headed up the program there.

“The really exciting, transformative piece of this work is that we have been able to take women who are very isolated to start to begin to feel connected,” she says. The women farm workers, many of whom work in the export agriculture industry planting and harvesting avocados, grapes, and asparagus, go on to train other women.

Women Farm Workers Vulnerable to Abuse on the Job

Some 564 million women work in agriculture, and those in commercial agriculture are predominantly concentrated in temporary, informal and seasonal jobs, where they receive low wages and few or no benefits, and are exposed to dangerous and unsafe working conditions.

Ayat Al Bakr, a farm worker in Jordan, says she joined the union because women farm workers are forced to work long hours with low pay in scorching sun. Credit: Solidarity Center/Tula Connell

“When I talk about women farm workers in Jordan, it is considered to be a huge army. There are tens of thousands of them,” says Ayat Al Bakr, a farm worker and union organizer in Jordan. “But it is suffering from low wages and inability to earn a decent livelihood.”

Al Bakr says she joined the union because of “oppression, long working hours in the sun, very high temperatures, wages very low” and safe transportation for the workers to and from the fields. But just as important, she says, speaking through a translator, she and other women farm workers want their employers to treat them with respect.

“When woman workers are talking to each other, the employer may yell at them, just because they are talking, insulting them, calling them names just because they are women,” she says.

Such verbal bullying and harassment is one manifestation of gender-based violence at work, which also includes physical and sexual abuse, as speakers discussed at the panel “#MeToo: Rural Women, Migrant Women, Sexual Assault, Access to Justice.”

Lupe Gonzalo describes a landmark agreement tomato farm workers won in Florida. Credit: Solidarity Center/Tula Connell

“For decades, women working in the fields carried the weight of disrespect” knowing they would be physically and psychologically abused on the job, says Lupe Gonzalo, a tomato farm worker and union organizer with the Coalition of Immokalee Farmworkers in Florida. “We couldn’t enjoy our time with our children at night because we knew we would go to the fields the next day and face the abuse again,” she says, speaking through a translator.

Gonzalo, who shared her story on both panels, described how the coalition succeeded in winning landmark agreements with corporate brands that enforce a code of conduct for growers who provide tomatoes. Through a 10-year campaign, 90 percent of Florida’s tomato fields now are covered by the code, which includes a zero tolerance policy for sexual abuse and other forms of gender-based violence.

“Now we can enjoy our time with our children with no shame or guilt and know we will go to the fields and be safe,” says Gonzalo.

‘Women Need the Space to Be Leaders’

Sponsored by United Methodist Women, Women in Migration and the Solidarity Center, the panel also highlighted efforts of unions and other civil society organizations to ensure the United Nations Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration now being drafted make gender a key part of the final document, which will be adopted in December.

Nalishha Mehta from the Solidarity Center discusses the campaign for passage of a an ILO standard on gender-based violence at work. Credit: Solidarity Center/Tula Connell

“Migrant women without status don’t have access to justice,” says Cathi Tactaquin with the Women in Migration Network and the National Network for Immigrant and Refugee Rights.

“Simply saying women cannot migrate is not a solution,” says Nalishha Mehta, Solidarity Center program officer. “Women do not need protecting. Women’s rights need to be protected. Women need the space to be leaders.”

Mehta discussed the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC) campaign for passage of an International Labor Organization (ILO) convention (standard) covering gender-based violence. Workers around the world could have access to a binding international standard covering gender-based violence at work after it is finalized. The Solidarity Center is among unions and other organizations around the world that have joined the campaign.

Despite their struggles, the women farm workers who took part in the panels say they are determined to continue working to ensure decent working conditons and dignity on the job for their sisters in the fields.

“All of the work we are doing is the beginning to end decades and decades of abuse and modern day slavery,” says Gonzalo. “We continue with our struggle because we now there are thousands and thousands of women who continue to be abused.”

Mar 15, 2018

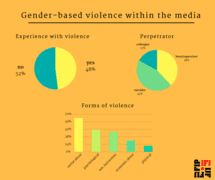

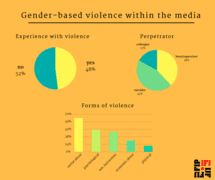

Nearly one in two women journalists have experienced sexual harassment, psychological abuse, online trolling and other forms of gender-based violence (GBV) while working—yet “up to three-quarters of media workplaces have no reporting or support mechanism,” says broadcast journalist Mindy Ran, citing results of a survey survey released this month by the International Federation of Journalists (IFJ).

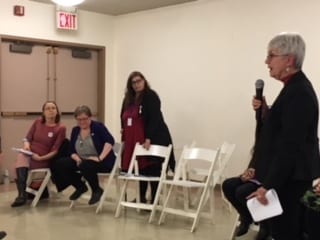

Ran, IFJ Gender Council co-chair, overviewed the survey findings yesterday at the panel, “Challenging Impunity and GBV against Women Journalists and Media Workers,” one of dozens of parallel events taking place this week in conjunction with the 62nd session of the United Nations Commission on the Status of Women (CSW) in New York City.

Credit: IFJ

Without safe and structured systems for reporting gender-based violence at work, employees are less likely to seek assistance—and, as the survey found, 66 percent of journalists who had experienced some form of gender-based violence said they had made no formal complaint.

“It is clear that the current approaches have had limited impact. We’re here to get practical,” says Ran, who opened the panel which included six experts in media and gender-based violence from around the world.

Journalists, like other workers, also experience gender-based violence outside their workplace while doing their jobs. The IFJ survey of 400 women in 50 countries found that 38 percent of perpetrators were a boss or supervisor and 45 percent were people outside of the workplace (sources, politicians, readers or listeners). Thirty-nine percent were anonymous assailants, such as through cyber bullying.

Gender-based Violence at Work: Global Issue Needs Global Solution

Mexico, one of the most dangerous countries in the world for journalists, has seen a “severe increase in violence against women journalists both online and offline,” says Aimée Vega Montiel, a research specialist in feminist communications at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México and vice-president of the International Association for Media and Communication Research (IAMCR). Yet there is a “cycle of impunity” and “media companies are not ensuring safety for women journalists,” she says.

Zuliana Lainez Otero, president of the Latin American Federation of Journalists and IFJ executive council member, agrees. “Media owners, at least in Latin America, don’t offer protection,” says.

Marieke Koning from the ITUC and the CLC’s Vicky Smallman joined the IFJ discussion on gender-based violence at work. Credit: Solidarity Center/Tula Connell

Gender-based violence occurs around the world, and is one of the most prevalent human rights violations. Yet few laws address even some forms of gender-based violence at the workplace, and those are not enough or not enforced, further enabling employers to ignore the issue. Marieke Koning, International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC) policy advisor for gender equality, discussed how union activists, women’s rights champions and their allies can take action by joining the ITUC campaign for passage of an International Labor Organization (ILO) convention (standard) covering gender-based violence. Workers around the world could have access to a binding international standard covering gender-based violence at work after it is finalized.

The Solidarity Center has joined the campaign, which Koning says can give momentum to gender equality activists around the world, as did the years’ long effort leading to passage of the 2011 ILO Convention on domestic workers’ rights. Like the domestic workers’ campaign, which built powerful support networks around the world, Koning says, “we want to build alliances to pass the gender-based violence convention.”

Male Media Control ‘Should Be Next on Feminist Agenda’

Domestic violence also impacts those at the workplace, and Vicky Smallman, director of Women’s and Human Rights, Canadian Labor Congress (CLC), shared details of a CLC survey of more than 8,000 union members that found 67 percent had experienced domestic violence. Of those, 47 percent say they were prevented from going to work by their abuser and eight percent lost their jobs because of ramifications from their abuse.

Following the survey, the CLC went on help unions negotiate contracts with paid leave for workers experiencing domestic violence, and successfully lobbied two Canadian provinces to pass similar protections. Smallman credits the Australian union movement for taking the lead on the issue.

Several panelists discussed how the lack of data on women’s experiences in the workplace, and the rates of specific forms of gender-based violence at work hamper efforts to define and address the issues. Carolyn Byerly, chair of the Howard University Department of Communication, Culture and Media Studies, described the lack of representation by women in the media documented in Global Report on the. Status of Women in the News Media. As principal investigator of the report, Byerly says the gender imbalances are still valid 10 years after the report was published.

Byerly and others also warned that media consolidation is creating a global web of male structural power that further exacerbates inequities and inequalities in newsrooms and in media coverage.

“The challenge we face is men’s control of media industries. The problem of media conglomerate is rampant around the world and is growing. We must put media ownership control on global feminist agenda,” she says.

Gunilla Ivarsson, former president of the International Association of Women in Radio & Television, discussed the association’s security handbook developed with a focus on women journalists, and ended the program, saying:

“I think we all have been affected in one way or another. It’s important for us to go to action for change.”