Nov 1, 2016

In 2003 as the Iraq War began, Wesam Chaseb, a young man with a college degree in physics, chose a job with the Iraq Federation of Trade Union (IFTU) Department of Training. His father had been involved in the labor movement until 1981, two years after Saddam Hussein took power. Under his 24-year reign, the rights of workers to form unions were rolled back, including a 1987 ban on collective bargaining, and union leaders were targeted and often killed. His deposition left uncertainty and potential for the future of worker rights in Iraq.

Despite the social divisions that the Iraq war has brought into focus, the Iraqi labor movement has built unity and solidarity among working people throughout the conflict. Merging with two other labor federations, the IFTU became the General Federation of Iraqi Workers (GFIW), and in 2015—after 12 years of movement-building and three years of collaboration with Parliament—the labor movement pushed a new labor code that defines the right to strike and includes the country’s first legal protections for victims of workplace sexual harassment. The law went into effect in February 2016.

Chaseb, who has managed the Solidarity Center’s work with Iraqi unions and workers since 2011, is particularly proud of the law’s prohibition on sexual harassment and discrimination in the workplace; its protection against arbitrary dismissals and the freedom to bargain collectively and strike.

“The first time, some said, ‘No,’ we don’t have sexual harassment in Iraq, we are not like other countries,” explains Chaseb. But after hearing back from women’s committees in several unions that had been established to review the labor code, union leaders became convinced legal protection of women union members against sexual harassment on the job was necessary.

“The leaders listened to the women,” he said.

The outcomes of Chaseb’s labor organizing may depend on lots of external factors, but he feels certain that his work is supporting one of Iraq’s best hopes for peace and social cohesion.

“I keep working with Iraqi unions,” he said, “because I’ve seen that they are the real face of Iraq. There is no discrimination among workers. They ask for an Iraq without violations of human rights.”

As a result, Chaseb says, “the change will start from unions.”

Passage of a new labor code was a significant step forward, but Chaseb is working with Iraqi unions on several other initiatives, including application of the new labor code to public-sector workers, as well as a Freedom of Association law that will bring the country in compliance with International Labor Organization (ILO) standards.

Oct 31, 2016

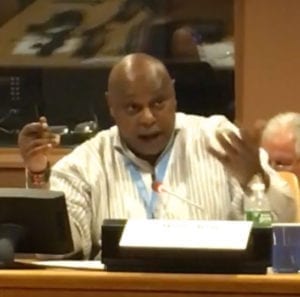

Millions of workers in the global economy have been disenfranchised from their rights, either tacitly or deliberately by governments, exacerbating “global inequality, poverty, violence and child and forced labor,” says Maina Kiai, United Nations Special Rapporteur on the rights to freedom of assembly and of association, in a frank report presented last week to the United Nations General Assembly in New York.

UN Special Rapporteur Maina Kiai says without freedom to form unions, workers have little power to change economic inequality. Credit: Solidarity Center

The Special Rapporteur also launched the report on workplace rights at a side event at UN headquarters, where he warned of “an assault on labor” that has been going on for years. The side event was co-sponsored by the Solidarity Center, AFL-CIO, Ford Foundation, Human Rights Watch and the International Trade Union Confederation. Shawna Bader-Blau, executive director of the Solidarity Center, facilitated the discussion.

Kiai’s report reveals that the majority of the world’s workers are sidelined, particularly women, migrant workers and people laboring at the bottom end of supply chains, without legal protections and denied a voice. Lacking assembly and association rights, he says, workers have little leverage to change the conditions that “entrench poverty, fuel inequality and limit democracy.”

Speakers at the side event confirmed that the erosion of rights in the workplace is a reality around the world. Over the course of four hours, panelists discussed freedom of assembly and association (FOAA) as it relates to fundamental human rights, working women, migrant workers and supply chains, business and human rights. Watch the video here.

Union Leaders, NGOs Describe Assaults on Worker Rights

Union leaders and other human rights defenders discussed freedom of assembly and association and its connection to basic human rights. Credit: Solidarity Center

Kyoung-Ja Kim, vice president of the Korean Confederation of Trade Unions, (minute 5:15) told the packed meeting room that workers in Korea who exercise their rights “are often treated as criminals.” She described a July 2016 march in support of worker rights, which ended with a violent police response that left a 69-year-old protester dead. Police were given immunity, yet the organizer of the protest was jailed, said Kim. In addition, when crane workers tried to negotiate with their employer and were refused, they went on strike. Their union was charged with a crime and leaders were convicted.

Swaziland, Africa’s last absolute monarchy, has lost access to the Africa Growth and Opportunity Act due to non-compliance with internationally recognized worker rights, said Vincent Ncongwane, secretary general of the Trade Union Confederation of Swaziland (min. 15:12). In addition, people are losing access to land. They are being evicted for their exercise of freedom of speech. And the right to protest is limited, he said.

Monserrat Mir Roca, confidential secretary of the European Trade Union Confederation, (min. 24:16) said that the right to strike is recognized in the constitutions of many European countries, and trade unions are recognized as legal actors to negotiate for better conditions for workers.

However, “Europe is in a crisis moment, and the first thing that governments try to do is reduce the right to freedom of association, the freedom to be in a trade union and to engage in collective bargaining actions.” Globalization, she said, has also globalized the response by governments and companies to economic downturns, to the detriment of workers. Strike leaders are threatened with criminal charges and long jail sentences in Spain, for example. In response, “we are engaging all our members to defend, in national parliaments, the right to freedom of association,” she said. “Democracy is in danger the moment trade union rights are not recognized.”

It is important that Paragraph 56 of the Special Rapporteur’s report “unambiguously defends the right to strike,” including as a matter of customary international law, said Jeff Vogt, (min: 32:30), director of the legal unit at the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC). He said attacks on freedom of association rights are increasing in frequency and come from surprising quarters, including the Employers Group at the International Labor Organization (ILO).

“In many nations of the world … domestic workers have not been recognized as workers … or even as human beings”—Elizabeth Tang Credit: Solidarity Center

“Since 2012, we have been in a pitched battle with the Employers Group at the ILO regarding the existence—the mere existence—of the right to strike. We have all assumed that the right has existed at the international level for a very long time and, at the very least, with the entry into force of Convention 87 of the ILO, which is the convention on freedom of association.” The right to freedom of association at work assumes the right to gather together, form organizations, bargain collectively and to strike, he said. Without all of those elements together, “the right is meaningless.” Indeed, a German legal decision said that “the right to collective bargaining without the right to strike is collective begging.”

Meanwhile, domestic workers are among the least protected of workers around the world, said Elizabeth Tang, general secretary of the International Domestic Workers Federation (min. 40:16). “In many nations of the world, for generations, domestic workers have not been recognized as workers … or even as human beings,” she said. “Ninety percent of the 60 million domestic workers lack effective social protections—and that is no accident. Where domestic workers are not recognized as workers, they cannot form trade unions.”

The participation of women in the labor market has increased—but has not been the often touted panacea for economic growth or women’s economic empowerment, according to Chidi King, director of the ITUC equality department, who moderated the panel examining issues related to working women and freedom of association (min. 49:30). On the contrary: The majority of jobs for women around the world are informal, precarious, pay poverty wages and are exploitative, with violence on the job a serious issue, she said.

Evangelina Argueta said women garment workers in Honduras have made some gains—through their unions—in boosting wages and making workplace safer, but women in export agriculture sometimes risk their lives when exercising their rights at work. Credit: Solidarity Center

Evangelina Argueta, who coordinates maquila organizing for the General Workers Confederation (CGT) of Honduras, (min. 57:24), said that while women garment workers—through their unions—have made some gains in terms of wages and safer workplaces in Honduras, women in export agriculture are caught in more challenging and dangerous circumstances. Pregnant women have been dismissed, worker rights advocates are blacklisted and protests are criminalized. Some companies overtly thwart the formation of unions by firing labor leaders. And around the country, women organizers are receiving death threats while the state does little to protect activists.

Purna Sen, director of policy at UN Women, (min: 1:06:52), said human rights features in all the work of the organization. The issues raised in the report, she said, are particularly timely as women’s economic empowerment is the theme of the 2017 Commission on the Status of Women meeting in New York. “The interconnections of human rights, labor rights and women’s economic engagement are absolutely critical,” said Sen.

All Workers Have the Right to Collectively Bargain

Gloria Moreno-Fontes Chammartin, ILO, says the right to collective bargaining applies to all workers regardless of status for ILO member countries. Credit: Solidarity Center

Opening the panel on migration and freedom of association, Gloria Moreno-Fontes Chammartin, ILO senior labor migration specialist, (min. 1:31:22), reminded the audience that freedom of assembly and association (FOAA) are core values of the ILO, and that FOAA is included in its constitution and Declaration of 1944. She outlined the various conventions and UN declarations (e.g., the 1998 ILO Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work, which commits ILO member states to respect and promote the four categories of principles and rights at work whether or not they have ratified the relevant eight conventions on freedom of association and the right to collective bargaining, the elimination of forced or compulsory labor, abolition of child labor and the elimination of discrimination in respect to employment and occupation) that reaffirm migrant workers’ rights, regardless of migration status or nationality. For example, the right to collective bargaining applies to all workers regardless of status in ILO member countries.

Despite international labor standards and agreements, the situation for migrant workers is often dire on the ground. For example, “migrant workers make up nearly 90 percent of workers in some Gulf states, but enjoy few to no labor rights,” said Sarah Leah Whitson, Middle East director for Human Rights Watch (min. 1:39:49)). She said that 15 million to 20 million people are migrant workers in the Gulf and cover every job, skill and education spectrum, with the largest concentration of migrant workers in construction and domestic work.

Most of these workers face “a triangle of oppression:” a kefala (sponsorship) system that puts the power in the hand of a private employer; the near-universal practice of employers confiscating workers’ passports of workers as “insurance”; and recruiting fees that are often a financial hardship for workers and keeps workers in bad jobs. Workers can spend two to three years working just to repay loans taken out to cover recruiting fees.

At the same time, many of the 9 million guest workers in the United States, who enter the country on special visas, are in “industries excluded from labor law, de jure or de facto,” and industries that “are of a direct lineage to slavery and are enmeshed in the same political economy of race,” said Saket Soni, director of the National Guestworker Alliance, (min. 1:49:15). Like the kefala system, a guest worker’s visa in the United States is tied to the employer, which leaves them vulnerable to abuse. Workers in seafood processing, for example, have reported grueling work conditions, forced overtime, harassment and exploitation.

In one case, Soni said, forced compulsory overtime coupled with the threat of retaliation was so severe that workers “developed the motor capacity to work while sleepwalking for entire shifts at night.” If they complained, the employer reported them to Immigration Services. In at least one case, the level of exploitation was deemed forced labor by U.S. courts.

Meanwhile, the creation of the “Asia global factory” has led to the largest rural-to-urban migration in the history of mankind, said Sanjiv Pandita, Asia regional representative for Solidar Suisse (min. 1:59:14). The global supply chain relies on an “institutionalized mechanism that harvests cheap labor,” pulling people from rural areas to factory zones.

He said workers move to escape poverty, but wind up on the lowest tier of the supply chain. They work long hours in dangerous workplaces for subsistence wages because they lack FOAA rights, while multinational corporations profit. “Asia has the largest population of working poor people. This is why we have a huge crisis of democracy because workers do not have rights to form unions and demand their fair share of the wealth being created,” he added.

‘We need to challenge the idea that supply chains are too complex to handle’

For the fourth and final panel—Supply Chains, Business and Human Rights—Cathy Feingold, director of the AFL-CIO’s international department, opened the session (min. 2:11:35) by issuing a call for a new global standard to address the more complex problems workers face, the agreements and standards that have been set aside, and the rules that were not designed for worldwide supply chains.

“How do you exercise rights when you don’t know whom you work for or if you are made invisible?” she asked. “We need mandatory due diligence in supply chains. We need to extend judicial remedy through supply chains. We need to take this out of legal and policy discussions and make sure workers know how to use remedies. We must have new, innovative, worker-driven approaches. … And we need to recognize that we are in one, single movement.”

Amol Mehra (image in video, above), director, International Corporate Accountability Roundtable (ICAR), agreed (min. 2:22:06). “We need to challenge the idea that supply chains are too complex to handle. There are inflows and outflows, and governments can set controls to protect rights,” he said. “Communities must come together to demand the rights they deserve. To build that power, we need to tackle global power,” he said. Mehra added that governments have a duty to protect human rights—and should start conditioning benefits to companies on how those companies respect these rights, including freedom of association.

Jo Becker, Human Rights Watch, says children produce 15 percent of world’s gold but suppliers don’t ask if child labor is involved. Credit: Solidarity Center

When it comes to supply chains and violations of human and worker rights, “the laissez-faire system of enforcement is not working. Companies intentionally go to countries with weak labor laws and weak enforcement,” said Jo Becker, (min. 2:30:52), advocacy director for Human Rights Watch’s children’s rights division, which focuses on supply chains in three sectors: clothing produced for major brand names, gold mining and tobacco. Children produce 15 percent of the world’s gold, for example.

“They climb down shafts, are involved in many dangerous processes, handle mercury causing brain damage,” she said. However, “we cannot know if a particular gold product is made with child labor. The chain of production and sale is long and complex. We find that due diligence breaks down in the earliest stages of this process. Company representatives don’t ask suppliers how gold was produced or if children were involved.” Without binding rules, some companies try to follow the Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, others do not fully understand them and still others ignore them. “We believe the rules should be mandatory,” she said. “It would eliminate the race to the bottom.”

Alejandra Ancheita says Mexico sees violations of human rights every day. Credit: Solidarity Center

Closing the session, Alejandra Ancheita described obstacles to freedom of association in Mexico (min. 2:38:47). The executive director of the Project of Economic, Cultural and Social Rights (ProDESC) said the country sees violations of human rights every day. For workers, “one big obstacle to freedom of association rights is protection contracts,” she said. “These are signed between companies and a management-controlled union. A real union cannot gain recognition because of this. And company profits go up by reducing pay and benefits of workers under these contracts.” Protection contracts protect companies, not workers, she said. “Good will is not enough. We must understand the ties between supply chains and joint liability” and work “to make rights a reality.”

Special Rapporteur Maina Kiai ended the discussion (min. 2:49:27) by exhorting participants to join together, to meld worker rights activism with human rights activism, including working together to ensure the right to strike is included in the general comment of the UN Human Rights Committee. “Let’s figure out a summit to bring together the human rights groups and labor. We can only succeed by coming together. … We have to protest and protest and protest,” he said. “Human rights are not neutral. They are very clear.”

Oct 28, 2016

In the past month, journalists and human rights activists in Uzbekistan have been arrested, interrogated and even beaten for documenting conditions of forced labor and raising awareness among workers about their rights during the country’s annual cotton harvest.

Every year, Uzbekistan mobilizes more than 1 million workers to pick cotton through a coercive system of forced labor. Most of those forced to work are students, teachers and health care workers, whose work, studies and services are disrupted for up to two months so they can pick cotton for the state.

From September through October, many schools and universities in Uzbekistan shut down, while health clinics and hospitals are understaffed or even closed as most of their employees are bused into rural areas to pick cotton.

“The cotton harvest policy is getting worse. It is not like it was before,” says one student in Jizzakh, explaining that now even high school students are helping with the harvest.

Political uncertainty following the death of President Islam Karimov and a poor growing season have made this year’s forced mobilization of workers “particularly aggressive,” according to the Uzbek-German Forum.

The government has set impossibly high production quotas—40 tons of cotton per district, when some districts only produce 10 tons per season. The attempt to maximize production is bad news for workers, who must face long hours in the fields harvesting more than 100 pounds of cotton per person every day.

Human Rights Activists Detained, Harassed

Human rights activists have been going into the fields, distributing leaflets about worker rights and taking pictures to document working conditions during the mass mobilization. The Uzbek-German Forum reports that several activists have been detained and harassed by police.

With annual revenues of more than $1 billion—almost all the earnings going to the central government—cotton is one of Uzbekistan’s chief exports, feeding into global supply chains that produce textiles and garments around the world. In fact, much of the cotton is shipped to Bangladesh, where garment workers often toil in unsafe conditions for low wages.

Workers report that living conditions during the mass mobilization are abysmal. They tell monitors working for the Uzbek-German Forum they work upwards of 12 hours a day and often are forced to pick cotton late into the night in the glare of tractor headlights. They are housed in empty, poorly insulated schools, where they must sleep on a cold floor without access to showers or bathroom facilities.

Those forced to toil in the cotton fields are expected to pick between 100 and 200 pounds of cotton per day, for which they are told they will receive between 120 and 150 Uzbekistani Som (less than 5 cents) per pound. Many workers report not receiving these wages and in fact, spend much of their own money buying warm clothes, decent food and transportation to the fields. Preparing for the harvest puts some workers, particularly students, into debt.

(For updates on the 2016 cotton harvest, follow From the Fields, a blog by the Cotton Campaign, a coalition of labor and human rights organizations that includes the Solidarity Center.)

Workers’ Lives at Risk

Many workers worry about what will happen if they get sick during the harvest, because they have neither enough money nor proper access to health care. At least one person has already died this harvest season, and one woman suffered a miscarriage after being forced to work while six months pregnant.

Before the harvest begins, workers are coerced into signing statements of voluntary participation that the government uses to deny accusations of forced labor. Students, doctors and teachers say local officials threaten to punish them if they refuse to sign the statements. Students risk getting kicked out of university, while health care workers and teachers are told they will lose their jobs if they do not participate “of their own free will.”

Uzbekistan was recently downgraded to the lowest ranking in the U.S. State Department’s 2016 Trafficking in Persons Report.

The government of Uzbekistan advertises cotton as a symbol of national pride, but as one student who toiled this year picking cotton says, “You work like a slave from morning ’til night. I have no strength left.”