Jun 2, 2017

Hundreds of garment workers in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, staged a peaceful demonstration this week to protest the firing of some 45 union leaders from the Haitian garment workers’ federation, GOSTTRA, and to push for a badly-needed minimum wage increase.

Hundreds of garment workers in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, staged a peaceful demonstration this week to protest the firing of some 45 union leaders from the Haitian garment workers’ federation, GOSTTRA, and to push for a badly-needed minimum wage increase.

According to GOSTTRA, the union leaders were fired to intimidate workers and discourage further demonstrations. A series of protests began May 19 when thousands of Haitian garment workers took to the streets in a peaceful response to dramatic increases in transportation and food costs spurred by a 20 percent rise in fuel costs earlier this month.

Unions are demanding a garment sector minimum wage increase to 800 gourdes ($12.50) a day to keep up with inflation, which was sparked by the weakening of the Haitian gourde against the U.S. dollar. Workers are currently paid 300 gourdes per day ($4.50) while paying exponentially higher prices for basic expenses.

Garment workers also are calling for food subsidies, paid transportation to work and subsidized housing, seeking fundamental economic stability to enable them to provide food, shelter and other basics for their families.

Garment Workers Find It Harder and Harder to Get by over the Years

A 2014 Solidarity Center survey of Haitian garment workers found that after insurance and social security deductions, most export apparel workers spent more than half of their salaries on transportation to and from the factory and a modest lunch, leaving little to sustain a family or keep a roof over their heads. Since then, the plight of Haitian garment workers has worsened, as wages have not kept up with soaring living costs.

Although the country’s Superior Council of Wages, which includes a labor representative, is currently considering an increase in the garment sector minimum wage, observers say it likely will not be high enough to cover garment workers’ basic living expenses.

In response to worker demonstrations, the Association of Industries of Haiti (ADIH) closed all garment factories at the SONAPI industrial park in Port-au-Prince on May 20 and 22, effectively locking-out workers. In announcing its decision, ADIH cited concerns of safety and security of personnel, equipment and property. In the following days, garment workers at two industrial parks in northern Haiti (CODEVI and Caracol) organized solidarity demonstrations.

Jun 2, 2017

In Cambodia’s booming construction industry, where up to 250,000 workers toil on building projects during peak season, laborers wear sandals or flip-flops and cloth gloves, if they have gloves at all, their heads covered only with towels or soft hats they bring to work.

One-third are women, who receive lower wages and are limited to the least skilled tasks that offer no opportunities for training and advancement. These construction workers risk their lives each day on the job, scaling tall structures without harnesses, helmets or other safety equipment and often are not paid for weeks. Their wages are disproportionately lower than the wages of foreign workers. At one site, for instance, a foreign worker receives $1,000 per month with a $300 allowance while his Cambodian colleagues receive between $160 and $240 a month.

Cambodia’s construction industry is one of the fastest growing sources of employment. In 2015, construction became the most dynamic driver of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP), outpacing the country’s garment and footwear industries. Corporations from China, South Korea, Japan, and Thailand—at least 18 countries in all—have directed 284 projects, a construction area nearly five square miles worth $4.3 billion, between 2000 and August 2016.

Cambodia Workers Have Little Freedom to Form Unions

The country’s lack of a labor inspection system to ensure compliance with national labor law allows employers to avoid receiving fines or other punitive measures when workers are injured on the job or are paid subminimum wages. As a result, construction workers do not have access to fundamental workplace rights like safety equipment, as stipulated in the country’s labor laws. Workers also receive little or no safety training.

“Based on a report we conducted in 2015, we discovered that more than 2,000 construction workers have been injured on construction sites,” says Yann Thy, secretary-general of Building and Wood Workers Trade Union Federation of Cambodia (BWTUC). “Out of this figure, 36 died.”

Yet when they seek to form unions and improve their working conditions, they often suffer retaliation, violence and imprisonment, as do garment workers and other workers across Cambodia, according to the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC).

A 2016 trade union law further limits workers’ ability to negotiate over their working conditions and pay. Cambodia is now one of 10 countries ranked the worst for working people, according to the ITUC’s annual Global Rights Index.

Despite the obstacles, BWTUC, assisted by the global union, Building and Wood Workers International (BWI), the Solidarity Center and other international rights organizations, assist construction workers across Cambodia to form unions, enabling workers to break the cycle of poverty perpetuated by low-wage, dangerous jobs.

From $1 a Day to $15 a Day with a Union

Angkor Archaeological Park generates $63.6 million in ticket sales but reconstruction workers are paid as little as $1 a day. Credit: Solidarity Center/Jennifer Bogar

When tourists enter Cambodia’s massive Angkor Archaeological Park, they are greeted by stunning temples carved with intricate sculptures built for the Khmer Empire, ruler of a large portion of Southeast Asia between the ninth and 15th centuries. Spreading over 154 square miles, the complex contains hundreds of buildings and monuments that had long decayed in disrepair.

Many buildings have now been restored, and while tourists encounter ancient structures resembling their original state, they are less likely to notice the construction workers laboring in often brutally hot conditions to make tourists’ trips Facebook friendly.

As a World Heritage site, Angkor is covered by United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) restoration and conservation guidelines which provide for architectural and environmental safeguards—but include no such protections for workers.

Chhen Sophal worked for years on the massive Baphuon Temple, eating little for lunch and dinner so he would have enough money to support his family.

With support of a union federation that later merged into BWTUC, and the global union movement, the workers held an official union election and ultimately negotiated with their employer, raising wages to $15 a day and securing payment in dollars, which are more easily exchangeable than the Cambodian riel. Through ongoing pressure, they also ensured their employer keep its commitments to provide health care, workplace safety improvements and full implementation of 18 days paid annual leave.

Yet Chhen Sophal, who was a union leader at the site, knows that hundreds of thousands of construction workers across Cambodia still receive below-poverty wages, and he seeks to improve conditions beyond his workplace.

“In the future, I hope that we will be able to push for a sector minimum wage for the restoration workers,” he said through a translator. “I want to stand up for wages for next generation—even outside of restoration and construction sector.” Chhen Sophal says he wants to ensure that if his children become construction or restoration workers, they will receive decent wages and their workplaces will be safe.

May 25, 2017

The Colombia Port Workers’ union is calling on the Ministry of Labor to follow up on promises it made during a congressional hearing this week and resume discussions with the union and the Buenaventura Port Society over formalizing 3,500 illegally outsourced workers in Buenaventura, Colombia’s largest port.

Solidarity Center union partners, organized within the Mesa Inter-Sindical coordinating body in Buenaventura, facilitated this week’s meeting in the Senate. The Solidarity Center has helped union partners to establish and build relationships with congressional allies, including Sen. Antonio Navarro, who visited the port in Buenaventura at the invitation of the port workers’ union in February.

The union (Unión Portuaria) is seeking an accord with the Port Society and government that establishes direct, indefinite employment contracts that include family-supporting wages, health care, severance, pension benefits and coverage by the union’s collective bargaining agreement.

Like the port workers, most workers in the city are classified as informal economy workers and excluded from the country’s labor protections, toiling in jobs that lack a minimum wage, workplace safety and other fundamental protections.

400,000 Residents Lack Clean Water, Electricity

Buenaventura accounts for 60 percent of the country’s maritime trade and in 2014, generated $2 billion in tax revenue. Yet the 400,000 residents, more than 90 percent of whom are of African descent, live in grinding poverty. Buenaventura residents lack even the most basic services, including access to clean water, reliable electricity and functioning sewage systems. Health care, housing and the education system are also substandard. The city’s three past mayors are in prison for embezzling public funds.

The port workers’ union, in coalition with 66 civil society organizations in Buenaventura, are also calling on the Colombian government to fulfill promises it made to residents in 2014 regarding access to basic services and decent employment. Residents have waged a civic strike in response to government inaction, bringing commerce and port operations to a halt.

Since May 16, tens of thousands of peaceful protesters have taken to the streets to demand dignity and peace. Over the weekend, police attacked the peaceful protesters, killing at least one demonstrator and injuring dozens more, including children.

Protesters vow to continue the strike until the government meets their demands, including:

- Access to basic sanitation, infrastructure, and community-run public utility services.

- Access to preventative healthcare, quality treatment and traditional medicine.

- Passage of legal and political measures to generate decent jobs, labor formalization with direct hiring relationships, and the elimination of outsourcing and employment insecurity.

May 22, 2017

Knowing that conditions in garment factories around the world should be improved is not the same as seeing those workplaces firsthand and talking with garment workers about their daily experiences on the job, as three Parsons Design students found out when they traveled from New York City to Cambodia.

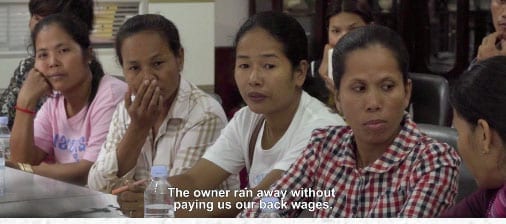

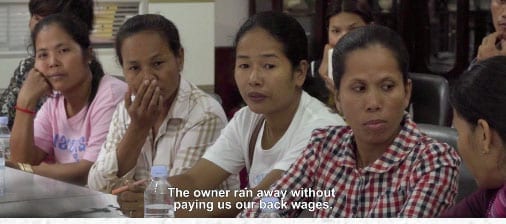

“Hearing their stories, and seeing that they are more than just a number, was something that was really eye-opening,” says Allison Griffin, a dual fashion-journalism major who took part in a video project by Re/Make, a U.S.-based non-profit organization focused on ethical production of clothes and other other garments.

Griffin, Casey Barber and Anh Le, all of whom graduated last week, met last fall with garment workers like the woman who described the high penalty she faces for making a mistake when assembling garments.

“If there are 12 pieces and I forget to put a code on one piece, they don’t pay me for any of them,” she says. “I get nothing for that day.”

She is among some of the more than 200 women whose employer last July abruptly closed the knitwear plant where some of them had worked for up to 18 years, leaving the workers without jobs or the more than $500,000 in compensation owed them.

Low Wages, Unsafe Conditions for Workers in Global Supply Chain

The tragedy of their story goes beyond a single knitwear plant in Phnom Penh. Workers throughout the global supply chain that fuels multinational corporations often face poverty wages, dangerous and unsafe working conditions, eroding rights on the job—and employers who find it all-too easy to abandon a plant in one country, only to open another elsewhere.

The students also met Sreyneang, a garment worker who invited the students to her home, where they met her two daughters whom she is supporting because her husband is unable to work.

“Every day when I finish my work (at one factory), I have to work at other factories until 9 or 10 p.m.,” says Sreyneang. “I walk home late.”

Sreyneang expressed hope the video can help improve the working conditions of Cambodia’s garment workers.

“It’s a lot to handle,” says Barber, speaking through tears on the video. “But hopefully we can make people understand and make change.”

May 19, 2017

Workers in Buenaventura, Colombia, who are waging an indefinite work stoppage to call attention to the lack of jobs, good wages and basic public services in their community, have brought port operations and local commerce to a halt.

As the country’s largest seaport, Buenaventura accounts for 60 percent of the country’s maritime trade and in 2014, generated $2 billion in tax revenue. Yet residents, more than 90 percent of whom are of African descent, live in grinding poverty. The vast majority of workers toil in the city’s informal economy, most in jobs that lack a minimum wage, workplace safety and other fundamental protections, in large part because their jobs are illegally subcontracted and so excluded from the country’s labor protections. (Follow the protest on Twitter at #SomosBuenaventura)

Buenaventura residents lack even the most basic services, including potable water, reliable electricity and functioning sewage systems. The city’s already weak health system worsened in 2014 when its only public hospital closed, and now the nearest hospital for the city’s 400,000 residents is a three-hour drive away, in Cali. Housing and the education system are also substandard. The lack of economic opportunity and investment in the city have fed an environment of violence as the country attempts to emerge from a 50-year armed civil war.

Workers who attempt to form unions to improve their wages and working conditions often are threatened and fired, and unions report receiving phoned death threats from men claiming to belong to paramilitary organizations.

The current work action arises from the community-building efforts of a coalition of unions and Afro-Colombian, indigenous and student groups. In 2014, the groups first mobilized for dignity and peace.

Protests in Buenaventura coincide with work stoppages and demonstrations across Colombia, in which at least half a million people , including oil workers and salt miners in Meta and Manuare, are protesting broken promises by the national government to alleviate rampant state neglect, poverty, violence and corruption.

Hundreds of garment workers in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, staged a peaceful demonstration this week to protest the firing of some 45 union leaders from the Haitian garment workers’ federation, GOSTTRA, and to push for a badly-needed minimum wage increase.

Hundreds of garment workers in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, staged a peaceful demonstration this week to protest the firing of some 45 union leaders from the Haitian garment workers’ federation, GOSTTRA, and to push for a badly-needed minimum wage increase.