Dec 5, 2014

Inequality around the world has its roots in the labor market, according to this year’s International Labor Organization’s (ILO) “Global Wage Report.” ILO research shows that increased worker productivity–particularly in developed economies, where inequality saw its widest increase—has had little effect on boosting wages. However, some emerging and developing economies, especially those focused on poverty reduction, did see inequality decline through a greater focus on more equitable wage distribution and increased paid (as opposed to self-) employment.

The ILO found that minimum wages contribute effectively to reducing wage inequality—and collective bargaining is “a key instrument for addressing inequality in general and wage inequality in particular.”

Some of the blame for flat wage growth can be laid on the 2008 financial crash, which pushed workers out of jobs and lowered growth rates in many economies. The long-term forces of globalization, technology and the decline of unions also have contributed to the problem.

“Average monthly real wages grew globally by 2 percent in 2013, down from 2.2 percent in 2012,” according to the report. Developing and emerging economies drove this growth: Asia saw a 6 percent increase, Eastern Europe and Central Asia nearly 6 percent and the Middle East saw real wages rise by almost 4 percent. Wages in Latin America and the Caribbean rose by less than 1 percent. Average wages in developed countries grew just 0.4 percent since 2009, despite a 5.3 percent increase in worker productivity.

Inequality fell most in Argentina and Brazil. Workers’ real wages in industrialized countries like Japan, Spain and the United Kingdom are less than they were in 2007.

In almost all countries surveyed, wage gaps remain between women and men, between national and migrant workers and between workers in the formal and informal economy.

According to the ILO, the gender “wage penalty” occurs despite education, experience and productivity, and often as a result of discrimination. Indeed, women’s average wages are between 4 percent and 36 percent less than men’s, and the gap widens for higher-earning women. Closing that gap will require policies to combat discrimination and gender-based stereotypes, and improve maternal, paternal and parental leave, says the report.

The ILO was created in 1919, as part of the Treaty of Versailles that ended World War I, to reflect the belief that universal and lasting peace can be accomplished only if it is based on social justice.

Read a summary of the full Global Wage Report.

Check out the Global Wage Report in Short (video).

Oct 31, 2014

Workers across Asia are taking to the streets this fall with protests against proposed World Bank policies that fall short of ensuring fundamental worker rights, like freedom of association and collective bargaining.

Worker right activists rallied outside World Bank meetings in the Philippines this fall. Credit: Alyansa Tigil Mina

In July, the World Bank released drafts of its revised Environmental and Social Safeguard Policies, a set of guidelines aimed to ensure that World Bank-funded projects do not harm communities or the environment.

The proposed safeguards for the first time would include a section on labor. But unlike international finance institutions such as the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, the World Bank would not require borrowers to adhere to International Labor Organization (ILO) core labor standards. Further, labor protections would extend only to workers employed directly by borrowers and exclude all employees of contractors or sub-contractors, who generally account for the vast majority of workers on World Bank-funded projects.

“The current draft of the safeguards … leaves especially vulnerable workers open to exploitation and abuse,” AFL-CIO President Richard Trumka said, noting that contract workers already disproportionately suffer from discrimination and unsafe working conditions.

Other proposed safeguards also fall short. As the AFL-CIO notes, “there is no enforceable provision to protect human rights, troubling exceptions to protections for indigenous rights and no clear process or procedure for individuals and communities seeking redress if things go wrong.”

Although the World Bank is consulting with governments, corporations and some non-governmental organizations, activists say the most vulnerable people—such as informal economy workers and indigenous populations—have been left out of the discussions.

“Instead of creating safeguards that favor corporations, what we actually need are provisions that will empower and strengthen the bodies that make up the labor forces. We don’t see that in the draft that is being circulated right now,” said Edsil Bacalso, coordinator of NAGKAISA, a network of labor groups in the Philippines and a Solidarity Center ally.

During a World Bank meeting discussing the safeguards in Washington, D.C., this month, a coalition of activists advocating for workers, human rights and the environment presented a statement signed by more than 170 groups demanding the safeguards be strengthened. As Soumya Dutta from the Indian Peoples’ Science Campaign read the coalition statement, activists in the audience took off jackets to reveal t-shirts saying: “Safeguard people and the planet, not corporate profits and human rights abuses!”

Solidarity Center staff from Thailand, Indonesia and Washington, D.C., took part in a forum in September to help craft the statement’s section on labor. Worker rights activists say that if the World Bank adopts the safeguards as currently written, it would set off a cascading effect, spurring multilateral development banks to weaken their labor requirements for borrowers and harming workers.

Activists are holding rallies around the world, including in Bangladesh, India ad Japan, timed to coincide with World Bank meetings in each country on the proposed safeguards. The World Bank is seeking to present the final draft safeguards during its meeting next fall.

Oct 20, 2014

A new data-driven online index launched by JustJobs Network, a nonpartisan global policy and research institute, highlights the need for sustainable employment and offers policymakers and other decision-makers worldwide a tool to help generate more and better jobs worldwide.

Created in partnership with Fafo, an independent and multidisciplinary research foundation, the JustJobs Index offers the first-ever index to measure both quantity and quality of jobs. The site includes two indexes with country-by-country data trends between 2000 and 2013. The Global JustJobs Index ranks 148 countries on quantity and quality of employment in 10 areas, such as unemployment and gender equality. The Enhanced JustJobs Index includes 41 countries where more extensive data is available, and offers 17 indicators. The site also provides longitudinal country comparisons, maps and downloadable reports.

The JustJobs Index is anchored in the International Labor Organization (ILO) decent work agenda and Article 7 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights recognizing the right of everyone to just and favorable working conditions. An accompanying report details the methodology underlying the data.

More than 200 million workers around the world are jobless, nearly 40 percent of them young workers, and many more—approximately half the global workforce—labor in the informal sector, where they lack basic protections. And even formal sector workers increasingly find their wages stagnant and their benefits stripped away.

JustJobs says the index should “provide a strong empirical basis for policy dialogue and formulations” as more policymakers and leaders around the globe recognize that high inequality is a sign that a country’s labor market is not producing enough good jobs and that work “is fundamental to the well-being of economies.”

Aug 7, 2014

Full employment should be a policy goal for all countries, regardless of level of development, according to the latest United Nations Development Program (UNDP) report. The report emphasizes the importance of meaningful, decent work for developing a worker’s dignity and creating community cohesion.

Full employment should be a policy goal for all countries, regardless of level of development, according to the latest United Nations Development Program (UNDP) report. The report emphasizes the importance of meaningful, decent work for developing a worker’s dignity and creating community cohesion.

“Sustaining Human Progress: Reducing Vulnerabilities and Building Resilience” also emphasizes that young people are especially at risk for unstable work because of lack of job experience and financial instability. Even employed young people are vulnerable, experiencing lay-offs and pay cuts during economic downturns. Despite the challenges, the report says, the growing youth population can potentially bring more educated and more productive workers into the economy.

According to the report, South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa have the highest rates of vulnerable employment—some 77 percent of the total workforce in 2011. The same regions have the highest rate of working poor. As far back as 1993, UNDP identified jobless growth, where output increases, but employment lags behind. In addition, even as productivity increased, workers’ wages remained fairly stagnant.

The report highlights South Africa among three countries experiencing improvements in equality of marginalized groups. Because apartheid left the workforce divided by race, leaving only unskilled jobs for minorities, the country introduced an Employment Equity Act in 1998. This act encouraged women and members of minority groups to participate in the workforce, reducing unemployment and poverty. The act, in conjunction with other more specific efforts, has helped change the racial distribution of South Africa’s workforce and included historically disadvantaged groups.

In a special contribution to the report, Juan Somavia, former director general of the International Labor Organization, says modern economic thinkers see work as “only” a production cost.

“Nowhere in sight is the societal significance of work as a foundation of personal dignity, as a source of stability and development of families or as a contribution to communities at peace,” he writes. Somavia then outlines his policy recommendations: living wages, respect for worker rights, gender equality, workers organization and collective bargaining and pensions, among others.

Stable, decent employment not only provides workers and their families with financial security but can also boost a sense of dignity and status within the community. Higher rates of female employment can also widely benefit communities, in part by changing the perception of the “value” of girls, increasing female education and reducing poverty.

Read the full report.

May 21, 2014

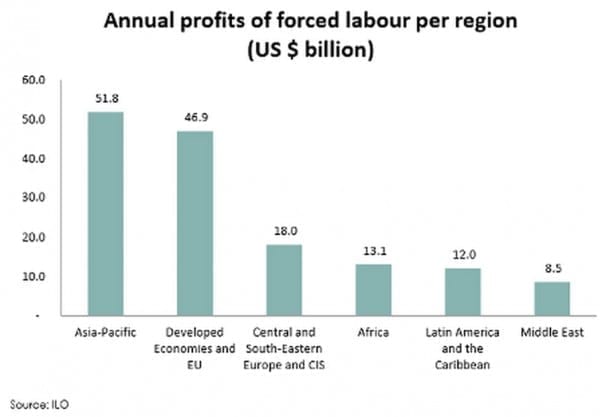

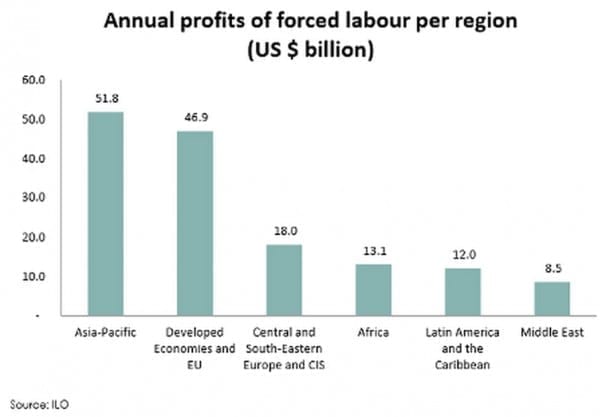

Some 21 million women, men and children are in forced labor, trafficked, held in debt bondage or work in slave-like conditions worldwide, and their toil generates an estimated $150 billion in illegal profits in the private global economy, according to a new report by the International Labor Organization (ILO). The $150 billion in illegal profits is three times more than the previous ILO estimate.

he majority of those in forced labor are women and girls, who make up 55 percent of the total, compared with 9.5 million (45 percent) men and boys. Many of these women are domestic workers. Of the 52.6 million domestic workers worldwide, the report estimates 3.4 million—6.5 percent—are in forced labor. Further, many domestic workers are migrants, often exploited by labor brokers and employers. The report notes that an estimated $8 billion is literally stolen annually from domestic workers in forced labor who, on average, are effectively deprived of 60 percent of their wages.

Overall, $51 billion of the estimated $150 billion in illegal profits results from forced economic exploitation, including domestic work and agriculture, areas where women make up much or most of the workforce. Commercial sexual exploitation accounts for $99 billion.

“Profits and Poverty: The Economics of Forced Labor” finds solid evidence for a correlation between forced labor and poverty. In countries where the ILO measured “income shocks” and food insecurity, such as Niger and Bolivia, a larger percentage of forced laborers than people who worked freely came from households where income had declined. In Nepal, only 9 percent of workers in forced labor had lived in food-secure households, compared with 56 percent of freely employed individuals.

The report finds the profit from forced labor is generated from three broad areas:

• $34 billion in construction, manufacturing, mining and utilities.

• $9 billion in agriculture, including forestry and fishing.

• $8 billion saved by private households by not paying or underpaying domestic workers held in forced labor.

An individual is considered to be working in forced labor, according to the ILO’s survey guidelines, if his or her recruitment was not free and involved some form of penalty at the time of recruitment, and if that individual works and lives under duress, and faces any penalty or cannot leave the employer because of the menace of a penalty.

• Read a summary of the report.

• Read the full report.

• In this video, ILO Director General Guy Ryder urges immediate action to end forced labor.

May 21, 2014

Uruguay, South Africa and Germany are some of the countries with the best worker rights records in 2013, while Cambodia, Guatemala and Nigeria are among the worst, according the 2014 Global Rights Indexreleased this week by the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC).

Uruguay, South Africa and Germany are some of the countries with the best worker rights records in 2013, while Cambodia, Guatemala and Nigeria are among the worst, according the 2014 Global Rights Indexreleased this week by the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC).

The annual index, which documents violations in 139 countries recorded between April 2013 and March 2014, found that in the past 12 months:

- Murder and disappearance of workers were commonly used practices to intimidate workers in at least nine countries.

- Governments of at least 35 countries have arrested or imprisoned workers as a tactic to resist demands for democratic rights, decent wages, safer working conditions and secure jobs.

- Workers in at least 53 countries have either been dismissed or suspended from their jobs for attempting to negotiate better working conditions. “In the vast majority of these cases,” the report notes, “national legislation offered either no protection or did not provide dissuasive sanctions” to hold abusive employers accountable. Rather, “employers and governments are complicit in silencing workers’ voices against exploitation.”

- Laws and practices in at least 87 countries exclude certain categories of workers from the right to strike. At least 35 countries impose fines or even imprisonment for legitimate and peaceful strikes.

The most frequent violation of worker rights occurred when workers went on strike, followed by violations of the rights of workers who sought to join unions.

The survey notes that because countries such as Qatar and Saudi Arabia exclude migrant workers from labor rights, more than 90 percent of the workforce effectively has no recourse for addressing forced labor practices which exist under archaic sponsorship laws.

“The World Bank’s recent ‘Doing Business’ report naively subscribed to the view that reducing labor standards is something governments should aspire to,” said Sharan Burrow, ITUC general secretary. “This new Rights Index puts governments and employers on notice that unions around the world will stand together in solidarity to ensure basic rights at work.”

The index assigns each country a score ranging from one to 5+, with 5+ indicating no guarantee of worker rights due to a complete breakdown in a country’s rule of law (for example, the Central African Republic and Ukraine), five indicating no guarantee of worker rights (for example, Bangladesh, Colombia, Malaysia) and “one” signaling that collective labor rights are generally guaranteed.

The report also offers a detailed look at six countries, one from each of the rankings: the Central African Republic, Cambodia, Kuwait, Ghana, Switzerland and Uruguay.

The ITUC Global Rights Index ranks the 139 countries against 97 internationally recognized indicators to assess where workers’ rights are best protected in law and practice.