Mar 15, 2019

Following the deadly mining dam collapse in January that buried alive 186 workers and residents of the town of Brumadinho, Brazil, and concurrent legislative attacks on worker rights, unions representing members across Brazil are requesting the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) investigate and address both issues.

The Vale-owned dam, which sat above Brumadinho, was held back by little more than walls of sand and silt, and is among 87 similarly constructed mining dams in the country. More than 131 people have not been found, and the “tidal wave of waste and mud that engulfed homes, businesses and residents” also wreaked enormous damage to the environment. The United Nations has said the disaster “must be investigated as a crime.”

The Brumadinho collapse, one of the worst mining disasters in the country’s history, follows a 2015 iron-ore dam collapse at another Vale mine that killed 19 people. Both catastrophes are the direct result of the privatization of Brazilian companies, a process that often results in precarious and dangerous working conditions, says Maximiliano Nagl Garcez, an attorney representing the unions.

Privatization in Brazil’s strategic sectors “means disrespect for international treaties, a threat to the country’s national and energy sovereignty and, above all, an enormous risk to the health and safety of thousands of workers at risk with negligence to their condition, to the detriment of an ever-increasing profit in the interests of large multinationals,” he says. Garcez will present the unions’ requests for investigations during the IACHR meeting in Jamaica in May.

Attacks on Worker Rights, Environment Connected

The mining collapse took place in an environment of stepped-up legislative attacks on land, community and worker rights, including the abolition of Brazil’s Labor Ministry and the transfer of oversight of indigenous lands and the forestry service to the Agriculture Ministry.

Most recently, the government enacted a “temporary law,” a measure typically reserved for emergencies, that changes the process of union dues collection. The impact of the new law is clear, says Garcez: It will destroy the financial viability of trade unions, undercutting their ability to effectively oppose the anti-worker government. These and other measures are a direct threat to workers’ right to freedom to form unions, he says.

The Central Union of Workers in Brazil (CUT) and other unions and organizations are requesting the IACHR address the attacks on worker rights, and Garcez requested hearings during upcoming IACHR investigations.

The Brazilian Bar Association this week challenged the measure to change union dues collection, and the country’s supreme court will hold a hearing on its constitutionality next week.

Mar 11, 2019

Women trade unionists in Indonesia and in Honduras and other Central American countries who are tackling gender-based violence at work often start by changing a culture of patriarchy within their own unions, according to speakers at a Solidarity Center-sponsored panel today in New York City.

Alexis de Simone, Robin Runge, Nurlatifah and Izzah Inzamliyah discussed strategies for ending gender-based violence at work. Credit: Solidarity Center/Tula Connell

“Unions in the past only focused on economic issues—gender-based violence issues have never been our priority,” says Nurlatifah, board member of the 341,000-member National Industrial Workers Union Federation (SPN–NIWUF) in Indonesia. But after she and other union leaders conducted an in-depth research project among women members that showed 81 percent had experienced gender-based violence, “the union tries to mainstream this issue into every activity the union conducts.”

Nurlatifah spoke on the panel, “Gender-Based Violence at Work and Social Protections,” co-sponsored by the Global Fund for Women, one of dozens of parallel events taking place this week in conjunction with the 63rd session of the United Nations Commission on the Status of Women (CSW) meeting March 11–22. The CSW, a global policy-making body dedicated to promoting gender equality and the empowerment of women, this year is focusing on social protection systems, access to public services and sustainable infrastructure for gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls.

Alexis de Simone highlighted how women in Honduras have addressed gender-based violence in garment factories and farm fields,

In highlighting how workers are organizing and building power to confront gender-based violence in Central America, Alexis de Simone, Solidarity Center senior program officer for the Americas, says years of leadership training among women union members in Honduras’s garment and agriculture sectors has led to more than 80 women becoming union leaders. They now negotiate contracts that address key women’s issues like maternity leave, and in the agriculture sector, have developed a cross-border network that shares contract language that benefits working women.

The Solidarity Center assisted many of those programs in Central America “and now is working with our partners in 17 different countries to support women worker efforts to define gender-based violence at work and to make it a priority with their unions,” says Robin Runge, Solidarity Center senior gender specialist and panel moderator.

Runge described the global union effort to secure passage of an International Labor Organization standard (convention) that would address violence and harassment at work, with a special emphasis on gender-based violence. Final negotiations are slated for June.

Expanding the Campaign to End Gender-Based Violence at Work

The Solidarity Center is supporting training that addresses gender-based violence in 17 countries—Robin Runge. Credit: Solidarity Center/Tula Connell

Women union leaders’ work challenging and addressing gender-based violence at work by focusing first on educating members and shifting union power dynamics that long favored men plants the seed for broader outreach.

Union leaders and members are now working toward passage of legislation in Honduras to address gender-based violence, says de Simone. And in Indonesia, SPN–NIWUF partners with some 50 organizations and unions in a nationwide campaign seeking government support for the ILO convention on gender-based violence at work. Meanwhile, the Indonesian Parliament “is actively supporting a campaign on gender-based violence because of the work the campaign has done to build consciousness,” says Izzah Inzamliyah, Solidarity Center program officer in Indonesia, who also helped translate for Nurlatifah.

Lawmakers would not have even considered such legislation before women across the nation raised their voices to end gender-based violence, she says.

Mar 11, 2019

Suthasinee Kaewleklai, coordinator for Migrant Workers Rights Network (MWRN) in Thailand, recently was honored for her work by the National Human Rights Commission of Thailand (NHRCT).

Suthasinee Kaewleklai, MWRN coordinator, recently was honored for her work by the National Human Rights Commission of Thailand (NHRCT). Credit: Solidarity Center/Robert Pajkovski

“Migrant workers are among the most vulnerable and abused workers in every country,” says Kaewleklai. “Worker rights are human rights, and migrant workers are entitled to fundamental rights without discrimination, including the freedom of association and collective bargaining. We will fight shoulder to shoulder with our sisters and brothers.”

Kaewleklai received the award during an NHRCT seminar last week, held in conjunction with International Women’s Day to honor women human rights defenders. The nonprofit MWRN, a Solidarity Center partner, has provided a crucial bridge between workers and access to legal redress for unpaid wages, occupational injuries and other forms of workplace abuse since it was founded in 2009.

“Whether they are protecting rights in the judicial process, fighting against impunity for rights violations, protecting democratic freedoms and the rights of communities and migrant workers, or fighting for freedom of expression, equality and the reduction of gender biases, their courageous stories are models and inspirations for future generations to learn and remember,” Angkana Neelapaijit, National Human Rights commissioner, said during the award ceremony.

Risking Physical, Verbal Assaults to Support Workers

Kaewleklai, a long-time trade unionist, began championing worker rights in the 1990s, when she worked at a factory in the Rangsit district, north of Bangkok. A co-founder of the factory’s union, she and other workers successfully challenged their employer’s refusal to regularly pay wages, and she successfully took legal action after the employer fired her and other union activists.

She later worked as coordinator for the Thai Labor Solidarity Committee, another Solidarity Center partner, and has championed the issues of working women, successfully campaigning to make International Women’s Day a national holiday.

At the MWRN, Kaewleklai advocates for the rights of migrant workers to form unions, negotiate with their employers for better working conditions, and urging lawmakers to ratify International Labor Organization standards on freedom of association and collective bargaining. She has helped migrant workers on chicken farms and elsewhere recover unpaid wages and attain safe working conditions.

She repeatedly has been verbally threatened, physically attacked and put under surveillance by state and non-state actors for her work to protect and promote labor rights and the rights of migrant workers. Currently, Kaewleklai, along with 14 migrant workers and other human rights defenders, is challenging criminal and civil charges filed by the poultry company, Thammakaset Company, following her advocacy on behalf of the company’s underpaid migrant workers.

Despite rulings by authorities and the courts against Thammakaset—including a January Supreme Court decision upholding a lower court ruling ordering Thammakaset to pay $53,600 to 14 former migrant workers for violations of the Labor Protection Act—the company continues to pursue charges against Kaewleklai and the others. Human rights defenders believe the charges are part of a strategy to harass human rights defenders and migrant worker rights advocates.

Mar 8, 2019

An independent,12-month monitoring program by a coalition of worker rights advocates in Kyrgyzstan found that the lives and safety of working people are at significantly higher risk than official data indicates—requiring urgent changes to the country’s occupational safety and health (OSH) monitoring system.

“I am asking government to take OSH issues into consideration because they envelop the lives of our workers,” said Eldiyar Karachalov, deputy president of the Kyrgyz union representing construction workers, at a roundtable briefing last month.

The event—which convened worker rights advocates, lawmakers, government administrators and employers for discussions on worker safety—highlighted data collected in 2018 by monitors from Kyrgyz metallurgy and mining, construction, garment and food processing unions and local NGOs Bir Duino Kyrgyzstan and the Insan Leilek Foundation.

According to official labor inspection statistics, 3,808 OSH violations and incidents occurred in 2018. However, the unions’ independent monitoring program found 500 previously unreported OSH violations and incidents—including 155 injuries and 15 deaths. Because most of the unreported OSH incidents occurred in informal-sector workplaces, unions are requesting that the country’s labor monitoring system be expanded into that sector. More than 70 percent of Kyrgyz workers are informal and so have little protection by trade unions or labor laws.

The entity with legal jurisdiction over Kyrgyzstan’s safety inspection system, StateEcoTechInspection, reports limited ability to collect data due to scarce resources. Since 2012, the number of full-time labor inspectors in Kyrgyzstan has fallen from 62 to 23.

“It is absolutely necessary to enlarge the labor inspection authorities and staff,” said Karachalov.

The unions and their NGO partners hope to present their data and recommendations to Parliament during an upcoming hearing on OSH reform. Union recommendations will include a call for adequate funding, an increase in the number of labor inspectors, better training of inspectors, employer-funded safety training for workers and employer-provided personal protective equipment for workers.

According to International Labor Organization (ILO) data, some 2.3 million women and men around the world succumb to work-related accidents or diseases every year, including 340 million victims of occupational accidents and 160 million victims of work-related illnesses. The ILO reports 11,0000 fatal occupational accidents annually in the 12-member states comprising the Commonwealth of Independent States—Azerbaijan, Armenia, Belarus, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, Russia, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan—but points to “gross underreporting” of occupational accidents and diseases in the region.

Kyrgyzstan is one of the region’s poorest countries. Although the official unemployment rate hovers around 8 percent, more than 1 million Kyrgyz nationals are estimated to be working abroad, particularly in Russia and neighboring Kazakhstan, where wages are higher but conditions for migrant workers can be dire. In Kyrgyzstan, the Solidarity Center aims to strengthen union representation to protect workplace safety and health and secure protections for Kyrgyz workers who migrate for jobs.

Mar 7, 2019

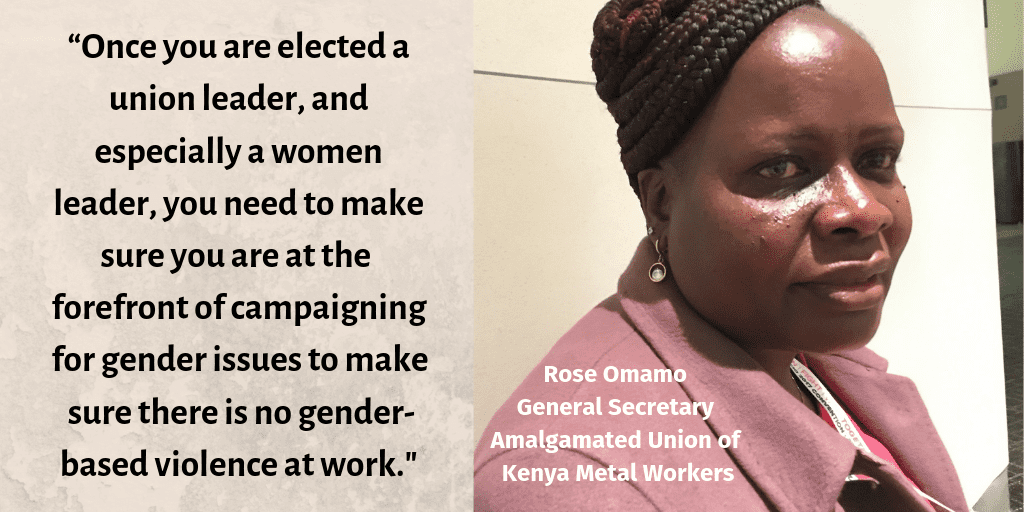

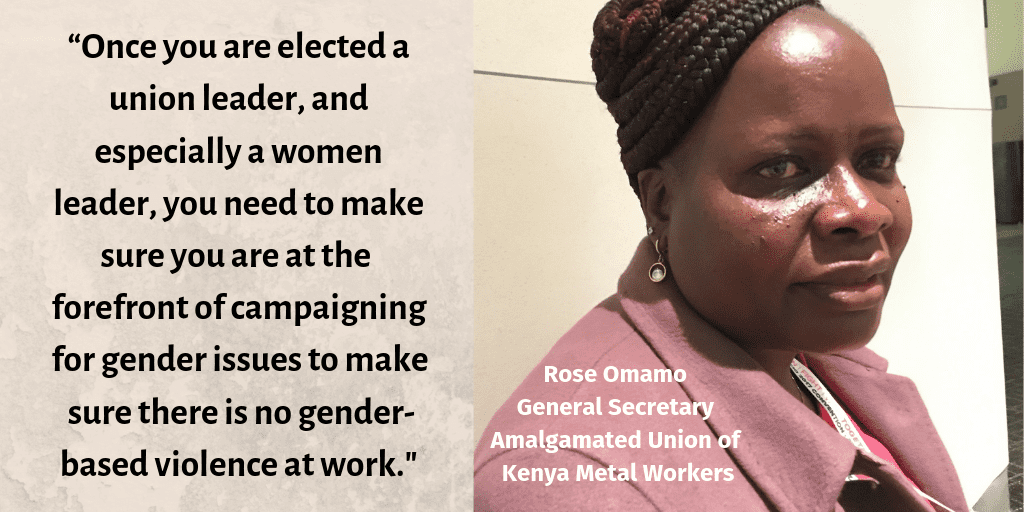

As the international community celebrates March 8, International Women’s Day, Kenya union leader Rose Omamo is meeting with union leaders and government officials across Africa to help propel passage of a proposed global standard that would address gender-based violence at work.

The convention (standard) under consideration by the International Labor Organization (ILO) would end violence and harassment in the workplace. Workers and their unions are championing its adoption with a strong focus on gender-based violence and harassment. Released last week, the most recent draft language of the proposed instrument, “Ending Violence and Harassment in the World of Work” builds on high-level talks in early 2018 among representatives of workers, government and business.

Rose Omamo discussed gender-based violence at work on a Kenya television station in February. Credit: NTV

“We believe we will be able to convince the governments and even some of the employers to support the convention,” says Omamo, general secretary of the Amalgamated Union of Kenya Metal Workers and national Women’s Committee chair of the Congress of Trade Unions–Kenya (COTU-K), a Solidarity Center partner.

In June, representatives of workers, government and business will negotiate final language on a binding convention and recommendation at the International Labor Conference (ILC).

“Our job is to lobby, lobby, lobby and make sure we get support,” says Omamo, who will be among worker representatives at the ILC discussions. She will be joined by union leaders from other Solidarity Center partner unions, including Eulogia Familia, vice president of the Confederación Nacional de Unidad Sindical (National Confederation of Labor UnionUnity, CNUS) from the Dominican Republic, and Fiona Gandiwa Magaya, coordinator of the Zimbabwe Confederation of Trade Unions (ZCTU) Gender Department.

Unions Drive Campaign to End Gender-Based Violence at Work

Unions around the world took the lead in spearheading the multi-year effort to secure passage of an ILO convention covering gender-based violence at work, with the Solidarity Center taking a key role in helping and supporting unions in leveraging their collective power. Unions, through which workers can take collective action to overcome barriers to preventing and addressing gender-based violence and harassment at work, are especially well-positioned to take the lead on this issue, says Solidarity Center Senior Gender Specialist Robin Runge.

Unions around the world took the lead in spearheading the multi-year effort to secure passage of an ILO convention covering gender-based violence at work, with the Solidarity Center taking a key role in helping and supporting unions in leveraging their collective power. Unions, through which workers can take collective action to overcome barriers to preventing and addressing gender-based violence and harassment at work, are especially well-positioned to take the lead on this issue, says Solidarity Center Senior Gender Specialist Robin Runge.

Workers and their unions are seeking a definition of violence at work in the final convention that would encompass transportation to and from work, an area in which employer groups are resisting. But Omamo believes it is imperative to include the time in which a worker commutes.

“For example, there was a company where workers reported very early in the morning. When the lady was going to work very early in the morning, when she was just crossing the railroad tracks, she was raped,” says Omamo. “These things are happening to us and are affecting us.”

Other issues include ensuring the final convention encompasses broad definitions of who is covered and what constitutes “violence and harassment.”

The International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC), which has helped coordinate and guide the campaign to end gender-based violence at work, offers information and tools to assist unions and organizations in taking action.

Building Support to End Gender-Based Violence at Work

Omamo and her sisters have been working doggedly over the past year to create awareness of and build support for passage of the convention. Omamo has traveled across Kenya to educate union members, such as engineers in glass, metal and petroleum, about the draft proposal.

As a representative on the gender commission of the Organization of African Trade Union Unity (OATUU), Omamo has met with government officials in Uganda and elsewhere to push for their support of the convention. In April, COTU-Kenya is hosting a meeting of women union unionists from the 18 OATUU member countries who will share input from their discussions with government officials, so the group can determine the level of government support for the convention and identify potential stumbling blocks going into the June ILC meeting.

When meeting individually with government leaders, Omamo says she describes the far-reaching consequences for workers experiencing sexual harassment and other forms of gender-based violence at work. “Some people even leave jobs because of the kind of harassment they go through at work—not because they don’t want to work, but because the bosses they have are sexually harassing them,” she says.

“Once you are elected a union leader, and especially a women leader, you need to make sure you are at forefront of campaigning for gender issues, make sure there is no gender-based violence at work, and make sure women are working in a safe environment,” says Omamo, who became the first woman to lead her 11,000-member union.

“This is a convention is very close to our hearts.”

Unions around the world took the lead in spearheading the multi-year effort to secure passage of an ILO convention covering gender-based violence at work, with the Solidarity Center taking a key role in helping and supporting unions in leveraging their collective power. Unions, through which workers can take collective action to overcome barriers to preventing and addressing gender-based violence and harassment at work, are especially well-positioned to take the lead on this issue,

Unions around the world took the lead in spearheading the multi-year effort to secure passage of an ILO convention covering gender-based violence at work, with the Solidarity Center taking a key role in helping and supporting unions in leveraging their collective power. Unions, through which workers can take collective action to overcome barriers to preventing and addressing gender-based violence and harassment at work, are especially well-positioned to take the lead on this issue,