Aug 2, 2018

The Constitutional Court of South Africa determined in a historic ruling late last week that workers placed by labor recruiters must be made permanent after three months at the company where they worked on temporary status, entitling them to the same pay, benefits and job security afforded to full-time employees, but labor organizations expect a protracted fight to enforce the ruling.

Zwelinzima Vavi, general secretary of the South African Federation of Trade Unions’ (SAFTU), described the victory as “unprecedented,” congratulating the National Union of Minworkers of South Africa (NUMSA) for its successful—almost four-year battle—through South Africa’s labor courts and the Constitutional Court.

The ruling puts employers on notice, he said. “Sorry, you are going to have to treat all workers the same” finally giving meaning to the ILO Convention which requires equal pay for work of equal value,” said Vavi in a broadcast interview.

However, the Court stopped short of banning labor recruiting, or broking, outright, for which South Africa’s unions and federations have long advocated. Short of a ban, workers say, trade unions and labor federations expect challenges to ensuring enforcement of the ruling.

Sizwe Pamla, a spokesperson of the Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU), said it was unfortunate that the ruling still “justified” labor brokers, whom he said were “trading in workers.”

NUMSA’s general secretary, Irvin Jim warned that workers “still remain vulnerable” under the new ruling because recruiters “will try to do every trick: They will try to replace the worker before three months [end]; they will try to remove him.”

South Africa’s workers have long argued that employers use so-called “temporary” workers to avoid the higher cost of employing permanent workers, an arrangement from which labor brokers profit.

To enforce the ruling, Vavi said, unions and federations must educate workers about their new rights under this ruling.

The Constitutional Court verdict overturns a 2015 judgment that labor recruiters and their clients are dual employers, thus making employers the direct responsible parties for all workers in their workplace after three months. Temporary workers earning $15,500 per year or less are covered by the ruling.

Labor recruitment in South Africa generated more than 2.5 billion U.S. dollars in 2013, employing over 1 million so-called temporary workers, or 7.5 percent of total employment.

Jul 27, 2018

Aldaberdi Karimov, 42, who lives in a remote Kyrgyzstan village in the Batken region, did not want to migrate from his country to find work to support his family, including his daughter, Ak Maral, now 5 years old.

But like many in Kyrgyzstan, where remittances from workers abroad make up more than 25 percent of the country’s gross domestic product, Karimov faced the heart-wrenching decision to leave his family to find employment. In fact, so few good jobs are available in the country, especially for workers in rural areas, only 24 percent of Kyrgyz workers are employed in the formal economy.

Aldaberdi Karimov escaped from forced labor and is back in his Kyrgyz village with his family, including his daughter, Ak Maral. Credit: Solidarity Center

And when he left his village, Karimov had no idea he would be a target of force labor and human trafficking. Globally, more than 21 million people are in forced labor, according to the International Labor Organization, which on July 30 marks World Day against Trafficking in Persons.

Forced to Live with Cows in the Barn

Karimov first sought jobs in Russia and then migrated to Kazakhstan, where he worked as a market vendor in Almaty, Kazakhstan’s largest city. Karimov thought he would fare better in Kazakhstan because, like Kyrgyzstan, it is a member of the Eurasian Economic Union.

Between 100,000 to 150,000 Kyrgyz were registered in Kazakhstan at the end of 2017, figures that do not reflect many who are not registered, according to a new report by the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH). Most work without written contracts or on contracts that do not adequately protect their rights. Their passports typically are confiscated by employers, making it difficult for them to leave abusive jobs, and they have no access to labor protections like safe working conditions and paid leave.

Karimov could not afford the permit needed to sell goods legally in Kazakhstan—costing between $1,500 and $2,000, a permit is the equivalent of a year’s wage. Through an intermediary, he and his brother, Giyazidin, were led to a job on a Kazakh farm in June 2016 tending 100 cows and 2,000 sheep. The farmer said he would pay them 40,000 tenge ($117) each per month.

“The employer promised to pay us not every month, but once every three or four months,” Karimov says. “After three months, we asked for an advance and our employer became very angry and said that the cows and sheep are very thin, so he is not going to pay yet.”

By October, they each had been paid only $100 for six months’ work. Frost and cold rains began and when the brothers asked to be housed in a warmer environment than their small thatched hut in the field, the employer told them to live with the cows and rams in the barn.

Tens of Thousands of Workers in Forced Labor in Kazakhstan

Essentially trapped in forced labor, the brothers made their escape after Giyazidin became so ill that the farmer took him to the hospital. Tens of thousands of workers are estimated to be victims of forced labor in Kazakhstan, with migrant workers from Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan forced to labor in agriculture, construction and the extraction industry.

Like many migrant workers, neither Karimov nor his brother reported their abuse to the police because they did not trust them. In fact, officers of law enforcement agencies often are the link between migrant workers and “buyers” of labor, according to the FIDH report.

Karimov says lack of a labor contract and no police protection left him and his brother vulnerable to human traffickers and inhumane working conditions. Around the world, most migrant workers are denied the right to form unions and bargain with their employer—a fundamental freedom that enables abuse and exploitation. “The lack of labor agreements entails forced labor and even slavery,” says Aina Shormanbayeva, president of the Legal Initiative, a Kazakhstan-based public foundation.

Now back in his village, Karimov says migrating for jobs is now out of the question, even as he searches for work, still seeking wages that will enable him to support his family

Jul 19, 2018

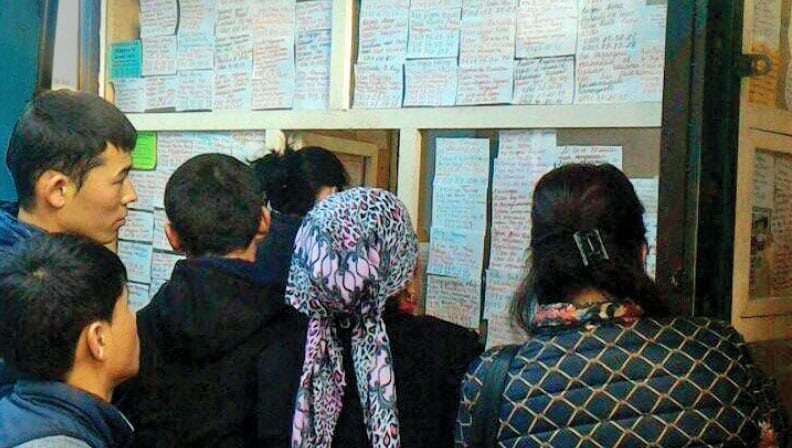

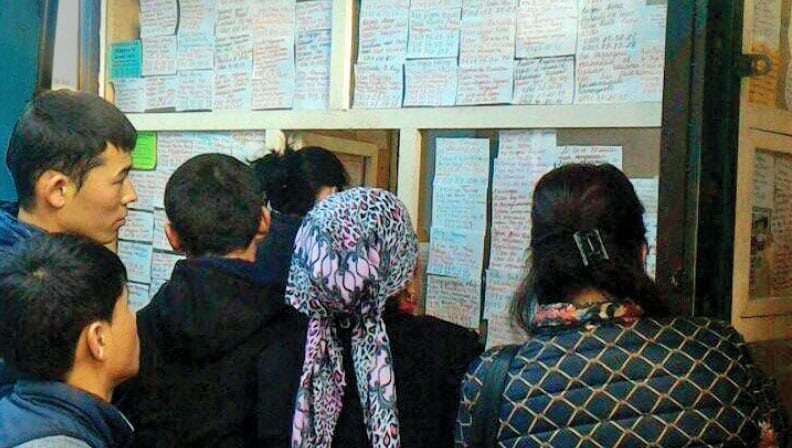

Workers who migrate from Kyrgyzstan to Kazakhstan for jobs often do not receive their wages, are forced to work in unsafe and abusive conditions and even are kidnapped and held against their will in forced labor, according to a new report.

“Invisible and Exploited in Kazakhstan” also found that children are forced to labor, with young girls between ages 12 and 17 working as nannies, and boys working in markets and on farms. The report is based on the findings of a series of missions by the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH) and its partners from September to November 2017 in Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan. The Solidarity Center contributed extensively to the report.

“The right to freedom of association is a core principle of human rights and worker rights, including when workers are migrating for jobs,” says Lola Abdukadyrova, Solidarity Center program coordinator. Abdukadyrova spoke yesterday at a press conference in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan, where the report was released.

Bedroom of five migrant workers in the basement of a construction site in Kazakhstan, November 2017. Credit: FIDH

Between 100,000 to 150,000 Kyrgyz were registered in Kazakhstan at the end of 2017, figures that do not reflect many who are not registered. Most work without written contracts or on contracts that do not adequately protect their rights. Their passports typically are confiscated, making it difficult for them to leave abusive employers, and they have no access to labor protections like safe working conditions and paid leave.

“The lack of labor agreements entails forced labor and even slavery,” says Aina Shormanbayeva, speaking at the press conference, which drew nearly two dozen reporters. Shormanbayeva is president of the Legal Initiative, a Kazakhstan-based public foundation.

Some 81,600 workers were victims of forced labor in Kazakhstan in 2016, according to estimates by the nonprofit Walk Free Foundation, with migrant workers from Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan forced to labor in agriculture, construction and the extraction industry.

Women Migrant Workers Targets of Gender-Based Violence

While some one-third of all migrants were women two to three years ago, the report finds women now comprise half of migrant workers. Women are especially vulnerable, facing gender-based violence in agricultural fields and in employers’ homes when working as domestic workers. They may lack medical care while pregnant and often are fired when employers learn of their pregnancy.

Says one woman migrant worker: “I work as a janitor from 9 a.m. to 9 p.m., and when there are banquets, until 3 a.m. or 4 a.m. Lunch breaks are 30 minutes maximum. There are no days off. I work every day. Some people can’t prove anything when they don’t get paid because nothing is documented. One woman worked at a car wash, they told her they didn’t have money and so they didn’t pay her. This happens to many people.”

Solidarity Center’s Lola Abdukadyrova, (second from left), discussed the plight of migrant workers in Kazakhstan during a press conference in Bishkek. Credit: Solidarity Center

The report finds migrant workers are not aware of their rights on the job, and they rarely appeal for protection of their rights when their employers perform illegal actions. They also do not believe police are able to protect their rights. In many cases, officers of law enforcement agencies are the link between migrant workers and buyers.

“Kazakhstan has not taken effective measures to prevent, investigate and prosecute persons involved in providing illegal intermediary services, and has not ensured effective legal protection for the victims,” the report states. Kazakh authorities argue that it is not their responsibility to protect migrant workers, and that protection of migrant workers is the responsibility of Akims (heads of regional or local authorities).

Kazakhstan was recently rated one of the 10 worst countries for workers by the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC). Union leader Larisa Kharkova was sentenced in 2017 to four years of restrictions on her freedom of movement, a ban on holding public office for five years and 100 hours of forced labor on false charges of embezzlement. Kharkova led the Confederation of Independent Trade Unions of Kazakhstan, which was ordered closed by a court ruling. Independent trade unions in Kazakhstan face ongoing attacks on freedom of association and basic trade union rights.

Over the past five years, the Solidarity Center in Kyrgyzstan has worked extensively to advance migrant worker rights, including holding awareness-raising campaigns for potential migrants and their families; supporting a hotline on labor migration issues; and assisting unions in protecting and promoting migrants’ worker rights.

Jul 19, 2018

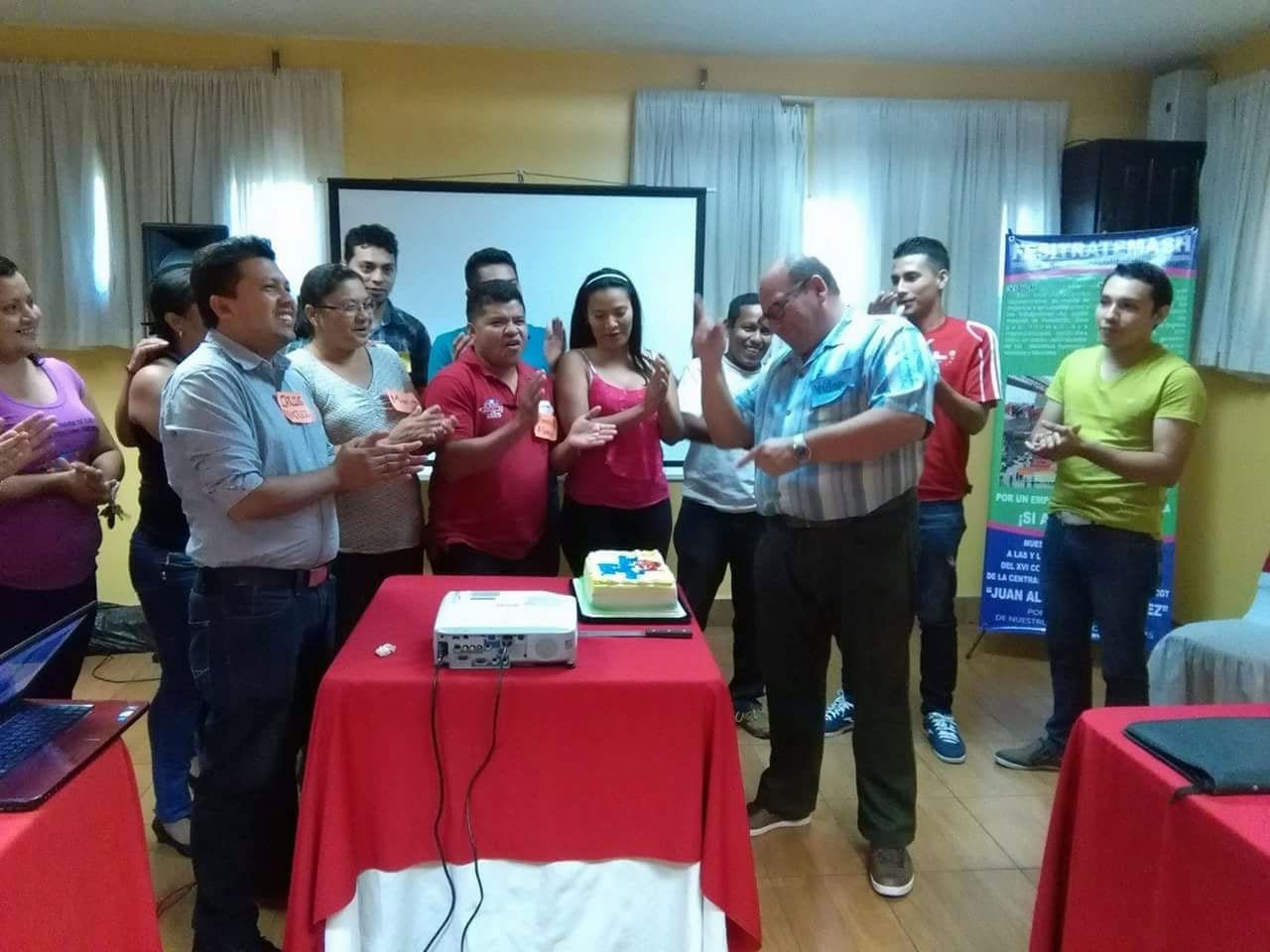

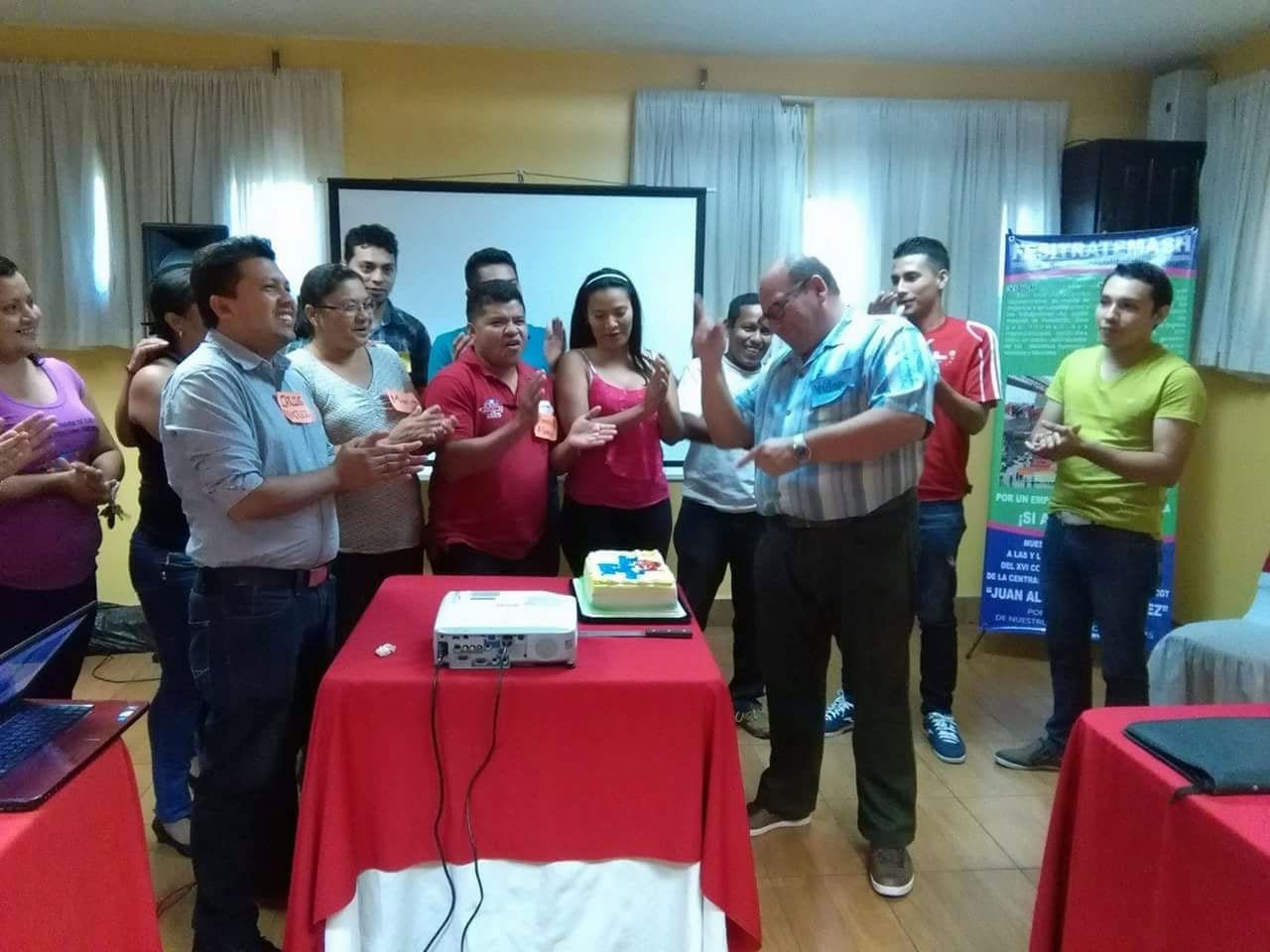

The Solidarity Center is mourning the loss of Victor Hugo Quesada Arce, Solidarity Center project coordinator in Costa Rica, who died July 16 after a battle with cancer.

“Victor was always a dedicated, passionate and joyful person,” says Stephen Wishart, Solidarity Center director for Central America. “He helped give workers courage, armed them with knowledge, and helped them rely on each other and this global labor movement we are all part of to build better realities for themselves and their families.”

“Victor was always a dedicated, passionate and joyful person,” says Stephen Wishart, Solidarity Center director for Central America. “He helped give workers courage, armed them with knowledge, and helped them rely on each other and this global labor movement we are all part of to build better realities for themselves and their families.”

In his 30 years of strengthening unions and educating workers about their rights, Victor worked side by side with some of the most vulnerable and marginalized workers in the region. He helped revitalize plantation worker unions which primarily represent migrant workers in Costa Rica and which had been decimated by decades of anti-union assaults.

Victor came to the Solidarity Center five years ago as a worker rights advocate well-known across the region, and agriculture unions from throughout Central America have been sending tributes and an outpouring of appreciation for his many years of solidarity and support.

“We stand in solidarity and send hugs to friends, relatives of our brother Victor,” writes FESTAGRO, the agriculture union in Honduras. “People like you are one of a kind, and are always remembered.”

Jul 18, 2018

Worker rights advocates are hailing a recent court decision in Thailand that dismissed criminal defamation charges against 14 migrant workers from Myanmar who faced jail time after reporting abusive working conditions on a poultry farm.

Fourteen workers who left the farm in 2016 described forced overtime, unlawful salary deductions, confiscation of passports and restrictions on freedom of movement in a complaint to the National Human Rights Commission of Thailand.

In retaliation against the workers for submitting the complaint, the Thammakaset Co. Ltd. filed a criminal defamation complaint against the 14 workers, alleging they falsified claims to damage its business interests.

The case put a spotlight on abuse in the supply chain, says Solidarity Center Asia Regional Director Tim Ryan. The ruling “strikes a blow against the criminalization of promoting labor rights,” and is a landmark for migrant worker rights and freedom of expression.

“Companies filing criminal defamation complaints against workers who seek justice on the job is an all-too common practice, one often used as justification for dismissal. This decision is in line with international legal standards supporting free speech, freedom of assembly and other activities key to an open civil society.”

Workers Increasingly Migrate for Jobs

One of the migrant workers says he worked 22-hour shifts for more than four years at the Thammakaset 2 Poultry farm, which supplies one of Thailand’s largest chicken export companies. Myint told the Guardian that each day, he would kill up to 500 birds for food processing. At night, he and his co-workers say they slept on the floor in a room with up to 28,000 chickens, swatting away insects. If a bird got sick, they were to blame.

Of the 232 million migrants around the world, 150 million are migrant workers. Millions of migrant workers like Myint and his co-workers are unable to find family-supporting jobs in their origin countries. With labor migration increasing as men and women seek to support their families, the case highlights the rights of migrant workers seeking justice for workplace abuse.

A team of United Nations human rights experts this year called on Thailand to “end recurring attacks, harassment and intimidation of human rights defenders, union leaders and community representatives who speak out against business-related human rights abuse.”

Referring to the Thammakaset case, they said “business enterprises have a responsibility to avoid causing or contributing to adverse human rights impacts; therefore it is a worrying trend to see businesses file cases against human rights defenders for engaging in legitimate activities.”

Thammakaset also filed a criminal complaint against two of the 14 workers and a Migrant Worker Rights Network coordinator for the alleged “theft” of time cards, taken by the workers to show labor officials evidence of their claims about a 20-hour working day. MWRN, a Solidarity Center partner, is a membership-based organization for migrant workers from Myanmar working in Thailand.

“Victor was always a dedicated, passionate and joyful person,” says Stephen Wishart, Solidarity Center director for Central America. “He helped give workers courage, armed them with knowledge, and helped them rely on each other and this global labor movement we are all part of to build better realities for themselves and their families.”

“Victor was always a dedicated, passionate and joyful person,” says Stephen Wishart, Solidarity Center director for Central America. “He helped give workers courage, armed them with knowledge, and helped them rely on each other and this global labor movement we are all part of to build better realities for themselves and their families.”